Editor's note: This is the fifth segement of a five part series. Read earlier segments in the series here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

When I visited the headquarters of Sonora SI in mid-June 2013, Hermosillo was burning hot. In June the Sonoran skies are a deep cloudless blue and the temperatures in Hermosillo regularly soar to more than 110 degrees. But as time goes by, the transborder West and most of the rest of the world, keeps getting hotter. This summer, on June 14, 2014, Hermosillo’s temperature broke historical records rising to 49.5 degrees Celsius -- 121 degrees Fahrenheit.

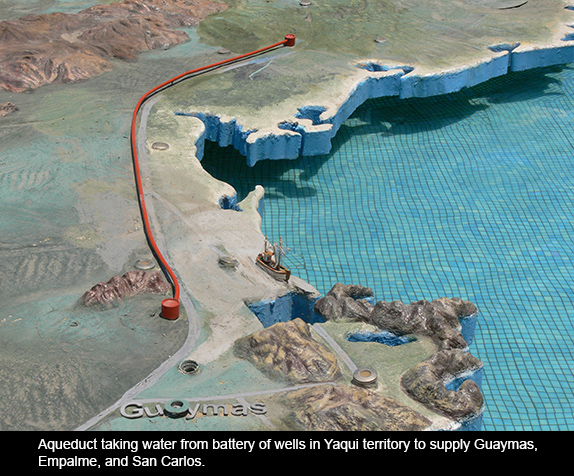

Sonora SI’s expansive lobby projects an optimistic view of the future of Sonora. Hanging on the walls are photographs and flat screens with audiovisual displays of the megaprojects in progress. Plastic models of the dams and other planned water projects adorn the lobby’s center.

From the air-conditioned lobby visitors can also take an open-air tour. An elevated walkway passes along an array of fountains that gush non-stop towers of crystalline water into the hot desert air.

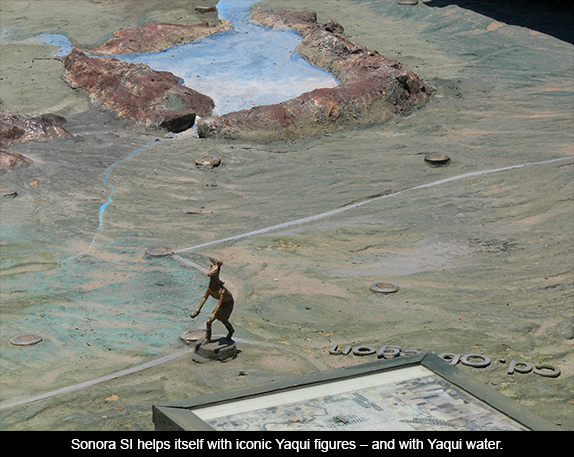

The path takes you on a tour of Sonora, as the walkway crisscrosses the mountains, deserts, and rivers represented on the immense topographical map that lies below. The jetting water from the fountains – reflected on the plate-glass of Sonora SI’s front wall – give the sense of boundless water resources. Adding to this illusion is the vast blue sea that wraps around Sonora’s west side.

Plastic models representing the network of dams, aqueducts, water-treatment plants, and pumping stations offer a vision of the planned hydraulic society.

No other visitors were taking a tour of Sonora SI’s molded vision of Sonora’s water future. The summer sun beating down on Hermosillo was intense, unrelenting, unbearable. While taking photos, I looked longingly at the door that would take me back into the frigid offices of Sonora SI. My tour guide – a Sonora SI engineer – had long since retreated to air-conditioned Sonora.

The current hydraulic infrastructure of Sonora has had its successes, no doubt. Cities and agribusinesses have flourished, and water-intensive mining operations are booming.

Yet, water conflicts are breaking out throughout the state. Poor neighborhoods in Hermosillo and other towns lack regular access to water. Salt is leaching up from aquifers and ruining farmland. All the state’s rivers – which once created deltas and emptied into the Mar de Cortés – now trickle into desert sand, often more than a hundred miles from the coast.

These are some of the challenges facing Sonora SI –not to mention the gathering threats of climate change.

Looking down at the extruded map of Sonora, there was just one human represented, appearing in the Yaqui Valley. It’s the same one found at the center of Sonora’s coat of arms – a lone Yaqui caught mid-step in the traditional dear dance of the Yaquis.

It is an image that remains from the old Sonora – when deer and other wildlife made their homes in Yaqui delta, and when Yaquis hunted, fished, and farmed.

Dams and Rivers

The three dams that block the natural flow of the Yaqui River – named after three Mexican presidents – were the proud accomplishments of Sonora’s first modern hydraulic society (1940-65). From the reservoirs, the river is channeled into irrigation canals that feed a maze of irrigation ditches in the Yaqui Valley. Meanwhile, for the past few decades, the Yaqui River has gone dry. When the river finally reaches the Yaqui communities in southern Sonora, it is a ghost of the river it once was, just a dry riverbed with puddles.

The Yaqui communities that once relied on the free-flowing river for their water and farms have been left without a river and without a source of clean drinking water.

Aside from the obvious implications for flora, fauna, and healthy seas – all of which are readily observable in the Yaqui coastal plains and coastal estuaries – the adverse impacts on traditional subsistence farming are also part of the detritus of Sonora’s hydraulic society.

Yet, such concerns don’t figure into the visions and hydraulic engineering of Sonora SI. Instead, Governor Padrés and Sonora SI insist they intend to ensure the “equitable distribution” of water and “water for all” in Sonora.

In the increasingly thirsty cities and drought-ridden rural areas, there is much support for such a vision. Yet, others insist that it is time to reexamine the premises of hydraulic societies that look to megaprojects to solve mega water problems.

Responses to “Sonora Water Wars, Part 5: Touring the New Hydraulic Society”