Editor's note: This is part four in a five part series. Read earlier segments in the series here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

Sonorenses take pride in their prominent role in forging Mexico. Four of Mexico’s post-revolutionary presidents were born in Sonora, including General Álvaro Obregón.

Sonorans also boast how they have defeated the climate and created a new Sonora in the historically uninhabited desert landscapes of western Sonora – with the exceptions of the Seris who made their homes along the coast and the Tohono O’odam who have for centuries scraped out a living in center of the Sonoran Desert.

Mexicans from other states commonly regard Sonoran pride – an attitude associated largely with the state’s elite – with disdain, regarding this famous pride as arrogance and a sense of superiority. In part, this criticism reflects a resentment and distrust related to Sonora’s historical connections and proximity to the United States. In part, too, Sonorans are generally taller and have more European features than elsewhere in Mexico.

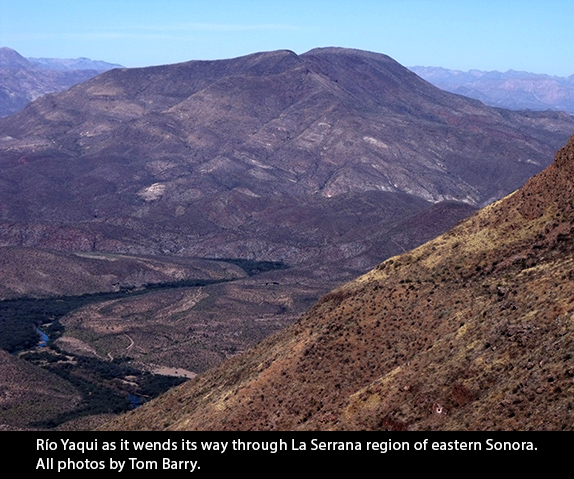

But Sonora has another reputation – one more grounded in the state’s mountain west than in the desert east. Typically, residents of La Serrana – Sonora’s land of mountains and narrow river valleys – boast of their independence and ruggedness.

When you enter a discussion about their state, you might hear Sonorans from La Serrana jokingly observe: “La civilización termina donde comienza la carne asada.” It’s a quote from the famous Mexican writer José Vasconcelos, who spent part of his childhood in Sonora, and roughly translates as, “Civilization stops at places where folks grill their meat over open fires.”

For intellectuals based in Mexico City in the early 20th century, the frontier territories of Sonora and Chihuahua were barbarous places, worlds apart from the more cultured society of Mexico City. Referring again to this south-north divide in Mexico and the independence and fierce spirit of the north, Vasconcelos later wrote: “Donde termina el guiso (balanced meals with more than meat) y empieza a comerse la carne asada, comience la barbarie.”[1]

Both the brave and barbarous currents in Sonora were found in Cananea during the brutal regime of Porfirio Díaz, whose decades-long regime fell to the revolution. Members of the Sonoran elite became presidents after the 1910-1917 Mexican Revolution. Yet it was the 1906 miners’ strike in the U.S.-owned Cananea copper mine that sparked the popular struggle against the hated Porfiriato.

The revolutionary corrido, “La cárcel de Cananea,” (“Jail of Cananea”), which memorialized the strike and the massacre of protesting miners, isn’t a part of the state’s history that is often mentioned by the government or Sonoran elite in boasts about Sonora.

Linda Ronstadt’s version on her “Canciones de mi padre” (“Songs of my father”) kept the corrido alive both in Mexico and in the United States. Ronstadt’s father and family hail from Banámichi, one of the villages hardest hit by the August 6, 2014 spill of 40,000 cubic meters of sulfuric acid into the Sonora River by the Cananea copper mine.

Sonoran pride cannot be missed in the declarations of Sonora SI (Integrated Infrastructure Systems). Governor Guillermo Padrés established this agency in 2010 to ramp up the state’s hydraulic infrastructure with a new package of water megaprojects, including an aqueduct to transfer water from the Yaqui River to the badly depleted Sonora River basin.

The agency describes itself as follows: “Sonora SI, System Integral, is the largest infrastructure and engineering program in the history of our state.” Sonora SI asserts that its water megaprojects program is “intelligent and visionary – and sustainable.”[2]

Following the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Model

In the late 1930s, the Mexican federal government launched an ambitious modernization program that included constructing a network of hydraulic infrastructure projects. The dams, reservoirs, aqueducts, and canals made “civilization” and agriculture possible in arid western and southern Sonora, mainly by tapping the water of the rivers of mountainous eastern Sonora.

Mexico closely followed the U.S. model of having the federal government subsidize irrigated farming in its arid lands. The U.S. Department of Interior created the Bureau of Reclamation in 1923 as an independent bureau to manage the hydraulic megaproject program. Similarly, in the 1920s Mexico’s revolutionary government launched its economic modernization program that aim to extend irrigated agriculture across northern Mexico.

Led by the National Irrigation Commission (created in 1926), the federal government began by assisting irrigation projects that were mostly the creations of U.S. investors. However, by the late 1930s the federal government was deeply committed to damming rivers to supply these faltering irrigation districts, like the one in the Yaqui Valley. The Hoover or Boulder Dam was the model for the first of three major dams in the Yaqui River basin – La Angostura, which was completed in 1942.[3]

The rapidly growing hydraulic society of the U.S. West also served as Mexico’s model for the subsidized electrification of the desert cities and irrigation districts of Sonora and elsewhere. Hydroelectric plants were coupled to the dam building – both counting largely on U.S. financing during the first decade or more.

Throughout Mexico, government entities – at the local, state, and federal levels – have again been calling for new water megaprojects to address the country’s acute water shortages. Sonora – the state that disproportionately benefited from Mexico’s hydraulic infrastructure projects – is leading the way to a new hydraulic future with its Sonora SI program.

Cynthia Hewitt de Alcántara, one of the most respected analysts of Mexico’s agricultural sector, described in her history of Mexican agriculture how Sonora, largely owing the creation of hydraulic society starting in the 1940s, became known as the “Mesopotamia de Mexico” and the “Agricultural Cornucopia of Mexico.” Since the late 1930s, one-fourth of federal spending for irrigation infrastructure flowed to Sonora. As a result, irrigated land in Sonora nearly doubled in two decades.[4] Eleven percent Sonora’s land is irrigated; no other state in Mexico having such a high percent of its agricultural land irrigated.[5]

Elected in July 2009, Governor Padrés can rightly claim to be leading Sonora’s hydraulic renovation. Shortly after he received the governor’s sash and moved into the Palacio del Gobierno, Padrés declared that he would create “Un Nuevo Sonora” during his six-year term (sexenio). With its plan for 22 hydraulic megaprojects, Sonora SI is the designated flagship program of the governor’s “Nuevo Sonora.”

[1] See blog “Ciudad Obregón en Sonora,” Aug, 29, 2010, at: http://obson.wordpress.com/2010/08/29/la-civilizacion-termina-donde-comienza-la-carne-asada/

[2] See Sonora Sistema Integral (Sonora SI), at: http://sonorasi.mx/web/

[3] Sterling Evans, “Damming Sonora: An Environmental and Transnational History of Water, Agriculture, and Society in Northwest Mexico,” Produced for Workshop in the History of Agriculture and Environment, University of Georgia, March 25, 2011.

[4] Cynthia Hewitt de Alcántara, La modernización de la agricultura mexicana, 1940-1970 (Mexico City: Siglo XXI, 1978), p. 131; Cited in Evans, Damming Sonora, p.6.

[5] Refugio I. Rochin, “Mexico’s Agriculture Crisis: A Study of its Northern States,” Mexican Studies 1, 1985, p. 257; Gary Paul Nabhan and Andrew R. Goldsmith, “State of the Sonoran Desert Biome: Uniqueness, Biodiversity, Threats, and the Adequacy of Protection in the Sonoran Bioregion, ” p. 34, cited by Evans, p. 6.

Responses to “Sonora Water Wars, Part 4: The Pride of Sonora”