A water war is getting in the way of traffic and free trade in the Mexican border state of Sonora. Trucks and cars come to a standstill about 350 miles south of the Arizona-Sonora border. Yaquis have mounted an intermittent blockade across international highway #15.

Wielding sticks and waving the Yaqui flag, the indigenous communities of the Yaqui river delta have since 2011 been demanding that the government stop taking water out of the Yaqui River. Traffic backs up in both directions from the Yaqui town of Vicam for as many as 12 kilometers before the blockade of the Nogales-Mazatlan toll road is temporarily lifted.

As the state government has stepped up its attempt to co-opt, corrupt, and repress the Yaquis, including ordering the arrest of its leaders, the Yaquis have become more militant and determined. The water war in northwestern Mexico is gaining adherents across Mexico and among environmentalists and human rights advocates in the United States.

It’s a water war that Governor Guillermo Padrés Elías sparked when in early 2010 he announced an ambitious plan to meet Sonora’s alarming water crisis with a network of hydraulic infrastructure projects, including aqueducts and dams.

Months after he took office in late 2009, Governor Padrés, a member of a prominent ranching family and leader of the National Action Party (PAN), committed the state government to construct a new phalanx of water megaprojects through an upbeat infrastructure program called Sonora SI (Integral System of Sonora). The government promoted the new water megaproject program as a revival of Sonora’s era (1938-1990) of building major waterworks -- addressing the arid state’s water limitations by damming rivers, transferring water via aqueducts, and subsidizing the intensive pumping of shrinking groundwater supplies.

From the governor’s first announcement of Sonora SI, it was never clear how the indebted state government would pay for the some two-dozen new megaprojects. At the same time, however, during his first two years in office Governor Pádres could count on the strong backing of President Felipe Calderón, a fellow PAN leader.

The Yaqui water war comes at a time when the state’s future is jeopardized by the expanding water crises in rural and urban Sonora. One view – that of Governor Padrés and Sonora SI – is that Sonora has enough water for all Sonorenses. All that is needed is a new network of waterworks to transfer water from water-rich areas to water-poor ones.

Others, however, already suffering from the ravages of climate change and diminishing river flows and depleted aquifers insist that Sonora’s traditional patterns of managing water are fundamentally and dangerously unsustainable. For the most part, however, the Yaqui water war highlights how increasingly different geographic, economic, and social sectors are determined to hold on to the water they have and to fight for more.

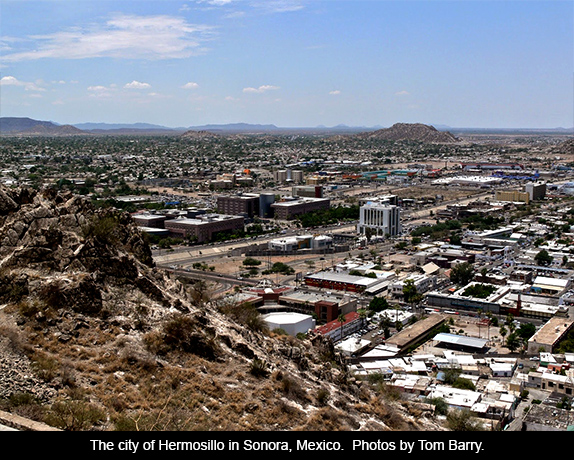

The immediate point of contention of the Yaqui water war is a new 155-kilometer Novillo-Hermosillo aqueduct, officially known as the Independencia aqueduct. For the past three years, the west-east aqueduct has been transferring as much as 75,000 Mm3 of river water from the middle Yaqui River basin in higher elevations of eastern Sonora to the state capital of Hermosillo, which lies in the heart of the Sonoran Desert.

Although the fight fundamentally revolves around indigenous rights and historic distribution of Yaqui River water, this escalating conflict underscores the unsustainability of tradition of hydraulic megaprojects in Sonora. Another contentious Sonora SI project is the planned Pilares dam on the Mayo River to the west of the Yaqui River – which constitutes an existential threat to the deeply impoverished Guajiríos indigenous communities in this remote region.

Instead of evaluating the flaws in the state’s reliance on hydraulic projects to capture surface and groundwater, Sonora SI, Governor Padrés, together with the city of Hermosillo, are committed to a new package of controversial waterworks – ones that transfer and further deplete water supplies rather than conserving water and altering water consumption patterns.

Desert Illusions

Since the early 1940s Sonora’s demographic and agricultural boom has been largely the product of hydraulic manipulation. Despite its aridness, Sonora is Mexico’s second largest agricultural producer -- virtually all the result of irrigation.

No other state in Mexico has been so dramatically transformed by the federal government’s network of dams, aqueducts, and irrigation canals. Agriculture accounts for 92% of water consumption in Sonora, and no other Mexican state is intensively irrigated as Sonora. Virtually all this agriculture occurs in the arid western plains and along the coast, where average annual rainfall is 8-15 inches, depending on the area.

Sonora is a classically “hydraulic society.” The term hydraulic society was coined by a German scholar who found that some of the earliest civilizations were based economically, politically, and theologically on water management.[i_]

In ancient hydraulic societies -- such as the civilizations in China and those that developed between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in the aridlands of Mesopotamia – the central authorities were the water masters. Their power stemmed fundamentally from their role in managing sophisticated irrigation systems and water-supply systems. If their subjects became thirsty, their authority and power would falter.

Closer to home and more immediate is California, which U.S. scholar Donald Worster and others categorize as a hydraulic society.[ii] In his paper “Damming Sonora,” University of Oklahoma scholar Sterling Evans wrote that Worster described the U.S. West as a “region characterized by ‘a social order founded on the intensive management of water,’ ‘communal reorganization,’ “new patterns of human interaction,’ and ‘new forms of discipline and authority.’”[iii]

Any discussion of hydraulic societies in the transborder West must note the seminal investigation and analysis of Marc Reisner in Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water. In his 1986 book, Reisner wrote: “Millions settled in regions where nature, left alone, would have countenanced thousands at best; great valleys and hemispherical basins metamorphosed from desert blond to semitropic green.”

You see the same miracle of hydraulic transformation in Sonora. Traveling south from the border at Nogales through the Sonoran Desert and then passing through the Yaqui and Mayo river deltas of Sonora – a nearly 7-hour trip – the fruits of Sonora’s hydraulic society are on display.

If one were to drive the nearly 400 miles from the border at Nogales to Sonora’s border with Sinaloa, you would cross three river beds (Sonora River, Yaqui River, Mayo River) that for the past several decades usually run dry as they head south and west toward the Gulf of California. Temperatures rise to 120 degrees or higher in the summer. Cactus, mesquite, creosote, and thorn trees define the natural landscape -- except for the vineyards and farmlands that bloom for miles around Hermosillo, Ciudad Obregón, and Navajoa.

How is it possible that Sonora has long been one of the top three agricultural states in Mexico? Even most Sonorenses don’t fully understand where all the water comes from for the state’s cities, industries, and agribusiness. That’s because most of the state’s hydraulic megaprojects lie in the isolated valleys of sparsely populated eastern Sonora, a region known as La Serrana (mountainous area).

Of the state’s five major dams and reservoirs, four are to the east of Sonora’s main demographic and farming belt along Highway 15 -- three on the Yaqui River and one on the Mayo River, each of which feed major irrigation canals leaving the rivers dry as they enter the former coastal deltas.

But the hydraulics of Sonora have been breaking down over the past two decades. Today, dams stand before empty reservoirs, hydroelectric plants stand abandoned, and government-subsidized irrigation projects have left vast expanses of coastal Sonora crusted with salt.

As the Sonoran government -- with more than two-thirds financing from the federal government -- continues with its water megaproject program, there is little reflection of the failures and consequences of Sonora’s “hydraulic society.” Instead most of those involved in the water wars in Sonora -- with the exception of small circles of environmentalists and academics -- look to inter-state and intra-state transfers of water.

Both sides of the Yaqui water war, for example, support a federal plan for an aqueduct that would bring water from the Nayarit and southern Sinaloa (two water-rich states along the Pacific coast) to Sonora.

[i_] Karl Wittfogel, Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957, as cited in Sterling Evans, “Damming Sonora: An Environmental and Transnational History of Water, Agriculture, and Society in Northwestern Mexico,” Discussion paper, March 25, 2011, at: http://whae.uga.edu/evans.pdf

[ii] Donald Worster, “Hydraulic Society in California,” in Under Western Skies: Nature and History in the American West (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

Responses to “Sonora Water Wars, Part 2: Reviving a Hydraulic Society”