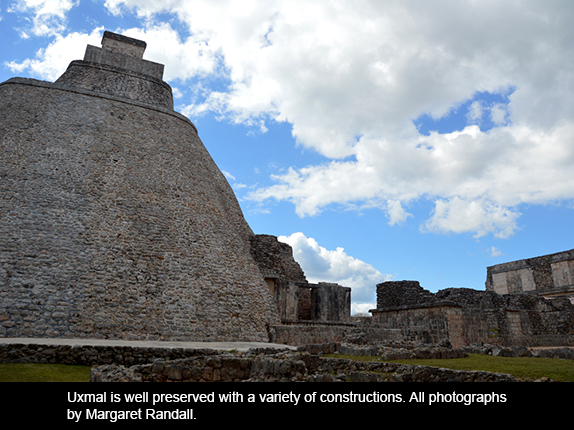

Uxmal (pronounced Oox-mahl) is a study in contradictions. The Maya city, an exquisite example of the Late Classic period, is only about forty miles south of Mérida, capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán. Its size and architectural richness make it one of the great centers, on a par with Chichén Itzá farther east or Palenque in the Mexican state of Chiapas, Caracol in Belize, and Tikal in Guatemala. Yet at its most expansive it is only believed to have housed some 15,000 people. And while the site has been consolidated and restored with great skill, little in the way of serious archeological excavation or research has been done there. Exact dates and population figures are rough guesses.

All this adds to Uxmal’s aura of mystery. Many factors contribute to an archeological site being chosen for the laborious work of digging and decipherment. Archeologists and ethnographers may prefer to continue explorations begun by their mentors or predecessors. Local authorities may advocate more or less successfully for experts to come. Funding may be available in one place rather than another. Still, it is hard to understand why the grandeur of Uxmal hasn’t attracted more serious study.

The first detailed account of the ruins was published by Jean Frederic Waldeck in 1838. Soon after, in the early 1840s, the prolific pair of John Stevens and Frederick Catherwood explored the site. Catherwood, who was an expert architect and draftsman, made so many and such accurate plans and drawings it was said they could have been used to construct a duplicate of the city. Unfortunately most of these drawings were lost. In 1860 Désiré Charnay took a series of photographs. When Mexico’s Empress Carlota visited Uxmal in 1863, local authorities removed some statues and architectural elements depicting phallic themes from the ancient facades, a gesture not unlike that of covering David’s genitals with a leaf. The great Mayan scholar Sylvanus G. Morley mapped the site in 1909. But the Mexican government didn’t take steps to seriously protect Uxmal until 1927.

Stevens and Catherwood were so taken with Uxmal that they visited twice, staying for months on both occasions. In his 1843 Incidents of Travel in the Yucatán, Stevens wrote:

In the afternoon, rested and refreshed, we set out for a walk to the ruins. The path led through a noble piece of woods, in which there were many tracks. […] emerging suddenly from the woods, to my astonishment we came at once upon a large open field strewed with mounds of ruins, and vast buildings on terraces, and pyramidal structures, grand and in good preservation, richly ornamented, without a bush to obstruct the view, and in picturesque effect almost equal to the ruins of Thebes.

Despite Stevens’ Eurocentric comparison, he was one of the early chroniclers most respectful of the Maya culture. And the accuracy and complexity of Catherwood’s drawings made them a valuable reference before photographic documentation became the norm. The pair did a great deal to publicize Maya civilization among those who still believed the only advanced cultures had existed in Greece, Rome and Egypt. Catherwood’s drawings continue to inspire artists (see my New Mexico Mercury article about Leandro Katz’ work at Site Santa Fe).

Stevens’ description of coming upon the ruins of Uxmal might work for us today. The preservation, art, and lack of obstructing vegetation combine with a respectful atmosphere created by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). Despite a great number of yearly visitors, it is still possible to visit Uxmal and wander undisturbed among its great buildings, sit in awe of a people’s culture only partially understood, soak up the beauty and feel of the place unperturbed by loud peddlers or gimmicky consumerism.

Which is just what I was fortunate to be able to do in February 2015.

I had long dreamt of visiting Uxmal. Over many years of living in, and traveling to, Mexico and Central America, I had seen much of what remains of the Maya world: Palenque, Chichén, Tulúm, and Cobá in what is now Mexico; Tikal and Quiriguá in Guatemala; Copán in Honduras; Lamanai in Belize; and even the early site of Joya de Cerén in El Salvador. I had also read voraciously. I still do. Uxmal and the other Puuc ruins remained places I longed to visit.

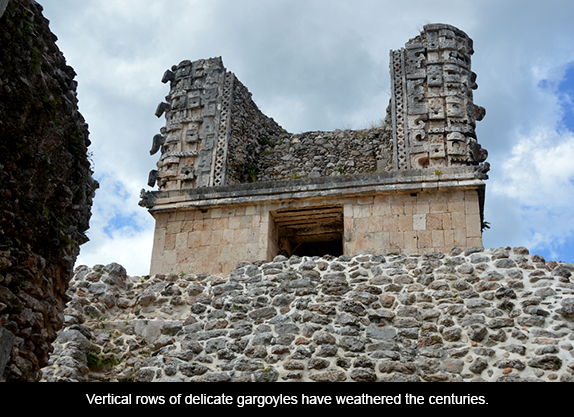

So we approached Uxmal much like Stevens and Catherwood, only 170 years later. We were my daughter Sarah, her sons Sebastián (13) and Juan (10), my partner Barbara and I. The site provoked different needs in each of us, so we split up at the entrance, agreeing to meet again a couple of hours later at the same spot. Sarah and Juan, both adventurous and extremely fit, covered a great deal of territory, climbed the single pyramid that permits ascension, and came back with marvelous tales to tell. Sebastián preferred to walk around a bit and then find a shady place to relax with his headphones, soaking up the atmosphere of the place. Older and less physically able, Barbara and I went more slowly, but were still able to explore pyramids and temples, courtyards and friezes, art that continues to astonish, including vertical rows of delicate gargoyles that have withstood the centuries. Barbara wanted to sketch. I wanted to photograph. And we both wanted solitude, which we got in abundance on this slightly overcast Wednesday morning in February.

One more contradiction that may have had something to do with Uxmal’s excellent preservation is that for generations the city was ruled by a single family: Xiu. Hun Uitzil Chac Tutul Xiu founded it around 500 AD, and made it the most powerful Mayan city in western Yucatán. For a while it allied itself with Chichén Itzá, and together they dominated the entire northern part of the Maya world. Sacbes, or ancient roads, still link the two cities.

Sometime around 1200, major construction ceased. This may have been related to the fall of Chichén and the shift of power to Mayapán to the northeast. When the Spanish arrived in the mid-1500s, Xiu allied himself with the conquerors. Perhaps this was the reason there was so little destruction of Uxmal’s buildings and art.

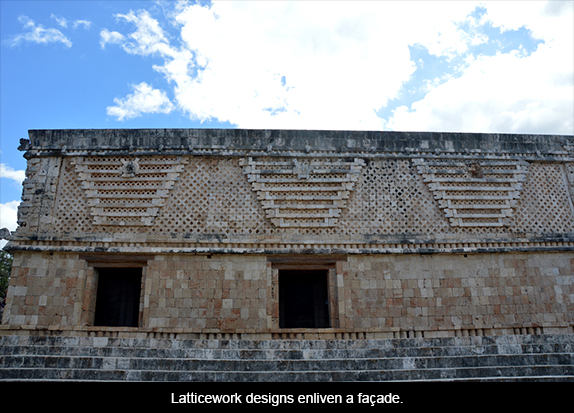

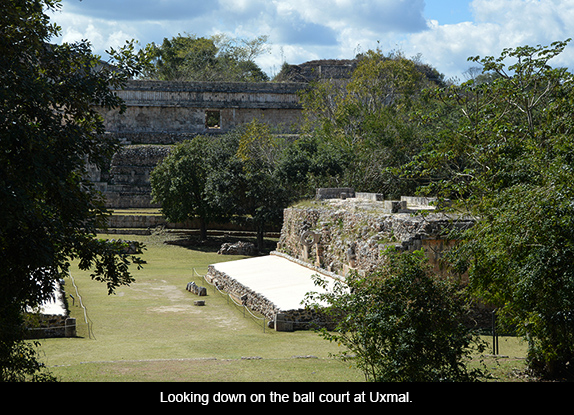

Pyramids, temples, a ball court, and many one-story buildings cover a vast area, with great arches and complex decorative elements. Add to this the fact that many of the surfaces were once plastered and covered in brilliant color, and you have some idea of the city’s great beauty. What we see today is more form than paint, more proportion than color. But a patina of what was once there seems to float just beyond our reach.

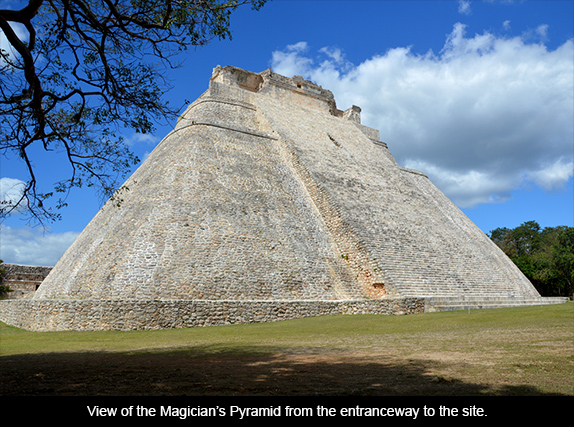

The first thing one notices, entering Uxmal from a very short pathway literally only yards from the entrance, is the pyramid called, alternately, Pyramid of the Magician or House of the Dwarf. This majestic five-level edifice differs from the pyramids at other Maya sites in several ways. It rests on an oval rather than a rectangular base. Each side presents unique elements. A large bird, perhaps a turkey vulture, perched on the uppermost level. At first I thought my eyes were deceiving me. Then the bird stretched its wings and took flight.

The dwarf refers to a Maya folk legend in which a certain gong was supposed to sound, signaling the fall of Uxmal to a boy “not born of woman.” One day the gong was struck by a dwarf who had not been born from a human mother but rather hatched from an egg by a childless old woman; locals say it was an iguana egg and the old woman a witch. The sound of the gong struck fear in the city’s ruler, who ordered that the dwarf be executed. The ruler reconsidered, though, promising to commute the dwarf’s death sentence if he could perform three seemingly impossible tasks, the most difficult of which was to build a massive pyramid, taller than any building in the city, in a single night. The dwarf built the pyramid, was hailed as the new ruler of Uxmal, and the structure was then dedicated to him. The similarities between this tale and those of other cultures speaks to prejudices, fears, and solutions present among many different peoples.

Stevens wrote:

Drawn off by mounds of ruins and piles of gigantic buildings, the eye returns and again fastens upon this lofty structure. It was the first building I entered. […] I stood in the doorway when the sun went down, throwing from the buildings a prodigious breadth of shadow, darkening the terraces on which they stood, and presenting a scene strange enough for a work of enchantment.

The enchantment remains. Legends of all sorts have been woven about this particular structure. The magician or dwarf clearly continues to exercise his powers at Uxmal. Many of the artistic elements at the site revolve around Chaac, the Maya rain god. I read somewhere that England’s Queen Elizabeth visited Uxmal in February 1975 for the inauguration of its Sound & Light show (dramatic displays, often including romantic versions of the history they give, which unfortunately have been created for the entertainment of tourists at ancient sites worldwide). When the Maya prayer to Chaac began playing over the sound system, a torrential downpour suddenly issued from a previously cloudless sky.

The story reminds me of an experience I had when I lived in Mexico City in the Sixties. An immense statue of the rain god Tlaloc had been loaded onto an 18-wheeler and was being moved from the state of Veracruz, where it had been found, to the capital where it would grace the entranceway to the recently opened Museum of Anthropology and History. Along with thousands of others I went to the Zocalo or central plaza, to watch the monument’s arrival. That day too dawned bright and clear. Precisely as the flatbed passed the spot where the great pyramid of Tenochtitlán had once stood (the Spanish had long since destroyed it and built a cathedral in its place), it began to pour. I remember standing with a friend, the poet Efraín Huerta. We looked at one another and smiled. The phenomenon didn’t surprise us.

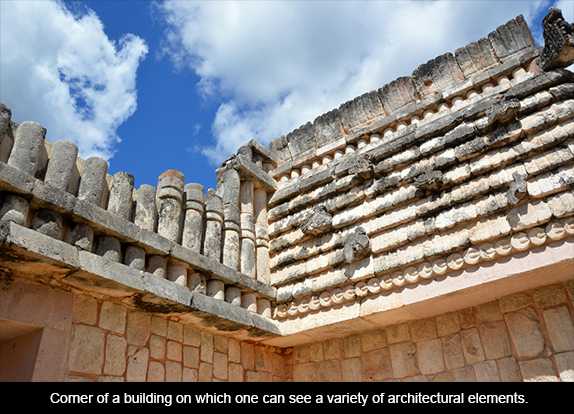

At Uxmal one immediately notices how the city’s builders took advantage of the natural rise and fall of the land to sculpt its contours. Landscape usage is proficient and spectacular. Taller pyramids and buildings occupy the higher areas. Lower constructions extend themselves around ample courtyards. The Governor’s Palace covers an area of almost 13,000 square feet. Many of the smaller buildings seem to be stone replicas of the huts common people lived in during the first millennia AD, with columns representing the reeds used in the simple homes and trapezoidal shapes representing the thatched roofs one still sees in local villages.

Uxmal’s decorative art is rich and abundant. There are many masks of the rain god Chaac. Their large noses are said to represent the rays of storms. I overheard a guide telling his group that when Chaac’s nose points down it is a plea for rain to benefit the crops; when it turns up it gives thanks for rain. Perhaps. Who knows? If the great scholars are forced to alter their assumptions every generation or so, local guides—whose training is rudimentary at best—undoubtedly invent stories they believe will thrill their clients.

My solution has long been to contemplate each generation’s findings and then simply wander these ancient cities, allowing my poet’s imagination full reign. Sitting quietly in the brief shade of a doorway or beneath an overhang, I love letting myself go back, back, to a different culture in a different time. I begin to see the ghosts of those who inhabited a site, observe their movements, hear their voices. I cannot decipher the words, nor do I try to. It is enough to be in the moment while welcoming into my mind and body a difference that can only be felt, not fully understood.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Yucatán II: Uxmal”