It’s often said that Mexico is a land of contrasts. With its great cities, many beaches (pristine and otherwise), thousands of pre-Columbian ruins, remote mountains and canyons, attention to ecological preservation, and overlay of present day indigenous as well as Spanish and French colonial cultures, it is cosmopolitan and vibrant. A residual independence dating to the Revolution of 1910 has made it unique in terms of promoting justice, at least on paper. Benito Juárez’ famous dictum, “Respect for the rights of others is peace,” has meant that the country has taken in refugees from around the world and provided support and comfort to many.

The art scenes of the 1940s through 70s, with names such as Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Nacho López, and Tina Modotti can still be appreciated in the great works these and other artists left behind. Today vast corruption spawned by drug cartels reinforced by the United States’ infamous “war on drugs” has turned large areas of the country into hotbeds of violence. US ex-president Bill Clinton recently apologized to Mexico for the ill-conceived “war on drugs.” Twenty-two thousand people have been disappeared by Mexico’s forces of law and order as well as by drug gangs over the past several decades. But the country remains alive, fascinating, and seductive. Today’s thinkers, writers, painters, architects, curators and scientists are involved in a multidisciplinary production that takes one’s breath away.

Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) protects and manages all the country’s archeological sites. Private lands have been bought by the State, and research involves experts from many other countries who, along with their local counterparts, continue the ongoing task of unraveling the mysteries of great civilizations such as the Olmec, Toltec, Aztec, and Maya. I recently visited the southern Mexican state of Yucatán, which alongside Quintana Roo occupies the peninsula that was home to much of the ancient Maya civilization (other Maya sites exist in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Belize). Today’s Maya continue to live there, providing a cultural bridge to the past. They are kind and gentle hosts.

Yucatán has been the subject of many books: from the few codices that survived the Spaniard’s brutal fires to conquest chronicles such as Friar Diego de Landa’s 1566 Account of Things of the Yucatán, in subsequent histories from every possible point of view, and some splendid novels. Among the latter, one of the greatest, strangely enough, is The Lacuna by North American Barbara Kingsolver. It blends fiction with history marvelously. The first time I read it I could hardly believe it hadn’t been written by a Mexican.

The Yucatán peninsula is believed to have formed some 65 million years ago when a large asteroid collided with earth, bringing about the extinction of the dinosaurs and causing the landmass to rise out of the sea.

There is so much to say about the Yucatán, from the experience of wandering through an ancient city to exploring a modern one and savoring local cuisine such as Poc Chuc, thinly sliced marinated pork served with a special achiote (tomato-based sauce), black beans, and fresh avocado. Fish and seafood are plentiful. Local dishes vary from village to village, and are often adorned with fried plantains and peas.

Many Yucatecan women still wear their richly embroidered shifts, or full-length huipiles: clean white cotton embossed with flowers and birds. This manner of dress also creates a bridge from modern times to the past.

There must be a thousand cenotes in the state. These are holes of varying depths, surrounded by lush vegetation, where the shelf of limestone has broken through and pristine fresh water rises with the season—spring “northers,” summer monsoons, and subsequent rains. The cenotes connect underground, forming great systems of subterranean tunnels and caves.

The Maya considered the cenotes to be sacred; some are known to have been places of human sacrifice. In the days of the buccaneers, many a clandestine smuggling operation was carried out through the cave systems running to the Gulf. Narco-traffickers also used them, and probably continue to do so. Today ejidos (community collectives) often tend them, and they are favorite swimming holes for locals and visitors alike.

The great Maya city of Chichén Itzá has a sacred cenote as well as several others. Indeed the site’s name means “at the mouth of the well of the Itzá.” In its day (from the Late Classic period around 600 AD through the Terminal Classic ending in 1,200 AD) Chichén was one of the great cities or mythical Tollans described in later Mesoamerican literature. At its height it is thought to have sheltered some 200,000 inhabitants. Today it draws 1.2 million visitors a year, making it the second most visited archeological site in Mexico (Teotihuacán, outside Mexico City, is the first).

Until quite recently (March 1910) the great pyramids and other elaborate buildings of Chichén were situated on private property. The state of Yucatán was finally able to purchase the site that year, and the ruin—like all Mexico’s archeological sites—is managed by INAH. This poses an interesting question. While almost all such sites are beautifully preserved and strictly controlled as to commercial degradation of the property, Chichén’s literally hundreds of souvenir stalls line every path leading into and throughout the site.

Different cultures practice different approaches to commercialism. Wherever it abides in the world, poverty always spawns desperation. Many of the great Egyptian archeological sites, such as Kom Ombo and Luxor, require that visitors make their way through a web of shops selling cheap trinkets before arriving at the ruins themselves. Egyptian peddlers can be particularly insistent. Although the US does a good job of managing its national parks, our country is certainly no paradigm of virtue when it comes to extreme commercialization. These days, a consumer mentality all but defines us.

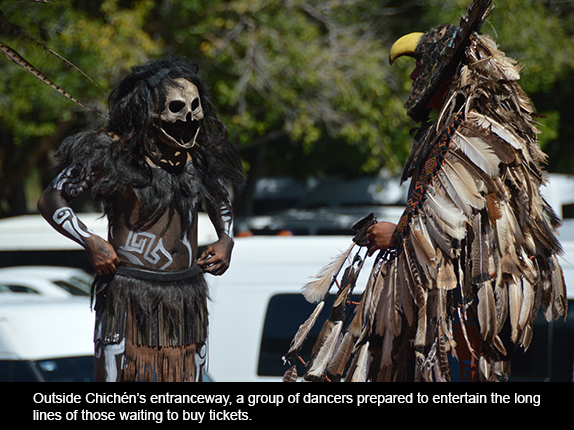

When I visited some 20 years ago, I remember being dismayed by the gauntlet of vendors I had to traverse along the path leading into Chichén. Once on the grounds themselves, though, tourists were mercifully free of their din. I hoped that Disneyesque path might have been closed down by now. On the contrary, in February 2015 things were much worse. Today throughout the entire site, on every path, in and around almost all the pyramids and temples, this scourge of hawkers has extended itself, become more raucous. There are masks fabricated in Taiwan and loud whistles meant to evoke the jaguar’s growl. Desperate voices advertise: “only ten pesos . . . almost free . . . common, lady, buy from me.” The poverty that promotes such assault is nothing less than tragic. Still, I have no idea why INAH preserves a dignified quiet at other ruins and allows this devastation at Chichén.

The tourists themselves, and the industry that caters to them, only make matters worse. Scores of guides, each with his version of history, stand in the middle of a huddle of visitors, giving misinformation mixed with information and clapping loudly to demonstrate the echoes that rebound from one stone structure to another. Tourists from around the world race about with their long selfie sticks, posing for pictures as if they are jumping from the heights of steep staircases. The selfie extensions are particularly annoying. I read somewhere that they were the most popular Christmas gift in 2014. Nowadays they are being banned by many museums, because they invade the personal space of others and out of fear they may damage the art. The day I was at Chichén, hundreds of bright pink umbrellas also bobbed about, shielding people from the hot sun.

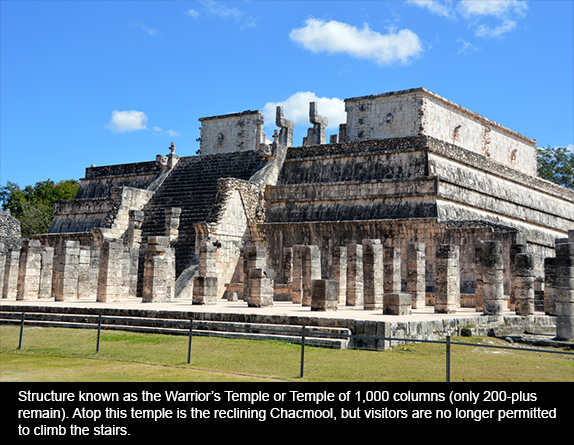

With all of this, though, it’s impossible to erase the grandeur that was this magnificent city. The pyramids, temples, ball courts (there are 13 at this site alone, one of them extremely large), colonnades, friezes, and other architectural features display a variety of styles; including the Puuc and Chenes as well as some from central Mexico. Experts once thought this great variety the result of direct migrations or even conquest by other groups, such as the Toltec. Today they believe it more likely that cultural diffusion created the mix.

As with many such ancient sites, modern chroniclers have named the different structures according to what they thought took place in each. At Chichén there is the magnificent Pyramid of Kukulcán, the Temple of Warriors with its more than 200 standing columns and a magnificent figure of Chacmool at the top (visitors are no longer allowed to climb this or any of the other pyramids, but one can discern the reclining figure from a distance), the Observatory, the Church, the Castle, the Temple of the Jaguars, the Platform of Venus, the Nunnery Complex, and others.

Writing about the castle in his Incidents of Travel in Yucatán (1843), explorer John Stevens observed:

The Castle is the first building which we saw, and from every point of view the grandest and most conspicuous object that towers above the plain. Every Sunday the ruins are resorted to as a promenade by the villagers of Pisté, and nothing can surpass the picturesque appearance of this lofty building, while women dressed in white, with red shawls, are moving on the platform, and passing in and out of the doors […] At the foot of the staircase, forming a bold, striking, and well-conceived commencement to this lofty range, are two colossal serpents’ heads […] with mouths wide open and tongues protruding […] No doubt they were emblematic of some religious belief, and in the minds of an imaginative people, passing between them to ascend the steps, must have excited feelings of solemn awe.

It is this solemn awe one would like to be able to recreate today, as one can at many of the other archeological sites throughout the country. Even the experts do not know precisely how the ancient Maya lived, what they believed, or how they saw the world in which they lived. We know they were masters of astronomy and mathematics. They invented the concept of zero, and their calendar astounds us. They also invented chocolate, for which some of us thank them delightedly. Their written glyphs are still being deciphered, aided by the relatively recent realization that some glyphs hide others within them. Their spoken language was obliterated by Friar Diego de Landa who, ironically, erased a culture even as he provided a European interpretation of it.

We know human sacrifice was practiced by the Maya, and although for decades they were assumed to be a peaceful people we now have ample evidence of their many wars. But can we speak about human sacrifice filtered only through our own cultural prism? I don’t think so. It was the loser in the ritual ball game, for example, who cut off the winner’s head. The winner presumably believed his demise would carry him to glory, or at least to the fulfillment of some deeply important promise. Let me be clear. I am not advocating human sacrifice, only pointing out that an accurate assessment of the Maya practice would entail a more complete understanding of their belief system than the one we currently possess.

Chichén Itzá is a magnificent place waiting to be restored to its natural peace and quiet when Mexico figures out that the overwhelming presence of needy hawkers detracts from a site of such magnificence. With 1.2 million visitors a year, one hardly expects solitude. But pride of place should be a given.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Yucatán, Part 1: Chichén Itzá”