Land. Land divisions. Land ownership. The people who inhabit land. Who draws the maps and whose interests do they defend? What cultures grow upon the land, are denigrated or usurped, and eventually destroyed only to rise tenaciously? Migrations across vast areas. Walls that slice lands (and cultures) in two, inevitably allowing some people in and keeping others out.

These are issues and concerns we in the US American Southwest know well. In one way or another, I have written of these themes, often for the New Mexico Mercury. I think of almost every travel piece. Of the article about the Circo Radical, in which young people spoke about boundaries in circus language. Of my ongoing fascination with the sites of ancient communities, where what is left of geography, architecture, and art require that we use our imaginations to begin to decipher how those who came before negotiated issues that continue to concern us today.

Unsettled Landscapes, at SITE Santa Fe, is a powerfully satisfying show. Forty-four artists, from Canada, Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Brazil, and the United States—among those from a variety of cultures in other countries—address questions of land, use and abuse of resources, and cultural legacy in multimedia constructions and two-dimensional representation. One visit wasn’t enough. My partner and I felt at once exhilarated and exhausted after an hour. We will return at least once before this show comes down.

In her essay “Invasive Species, Restlessness, Disturbances, and other Events,” included in the exhibition’s handsome catalogue, Lucy R. Lippard tells us: “Non-native plants, or invasive species, are known to thrive on disturbed land. Unsettled Landscapes is an ironic title for this exhibition, since settled/inhabited landscapes—the apparent opposite—have caused the unsettling effects produced by territory, migration, trade/transportation, and lingering colonial concepts of representation.” She adds “[w]e are unwilling residents on other ‘frontiers’ where battles are being fought over the ongoing destruction of our local landscapes by extraction industries—struggles common to the entire hemisphere. TransCanada’s XL Pipeline, for instance, is actively resisted not only by a massive national movement, but also by a large number of Native nations, notably in the Northwest. The human thread running through this exhibition is woven into broad ecopolitical concerns.”

Lippard goes on to say that “Unsettled Landscapes launches SITElines, the first First-World hemispheric biennial (preceded only by the Bienal de la Habana),” and notes that the show is “especially significant for the extent to which it acknowledges indigenous heritage and influence. A number of the artists, and co-curator Candice Hopkins, are enrolled members of Native nations across the Americas. Perhaps more importantly, they are integrated into contemporary art’s larger socio-aesthetic dialogue—a longtime goal of Native artists resisting stereotyped ghettoization.”

This is an immense and immensely important series of interwoven topics.

Although every artist represented in Unsettled Landscapes caught my attention and stimulated lines of imagination and inquiry, a piece of this length can never hope to do them all justice. For personal reasons, I will focus on Argentinean/US artist Leandro Katz’ Catherwood Project. Unsettled Landscapes includes a small but intensely moving piece of this project on which Katz worked for more than two decades. He describes it as “a work about time.”

I have followed Katz’ work for many years. Born and raised in Argentina, deeply traveled throughout the American continent, and having lived and worked for many years in the US, he has been back in Buenos Aires for almost two decades. His artistic expression has found compelling outlets in poetry, film, and large multimedia constructions. Most meaningful, for someone like myself who shares a generation’s search for justice and profound losses, his work looks at that search and those losses with complexity and nuance. No easy answers here.

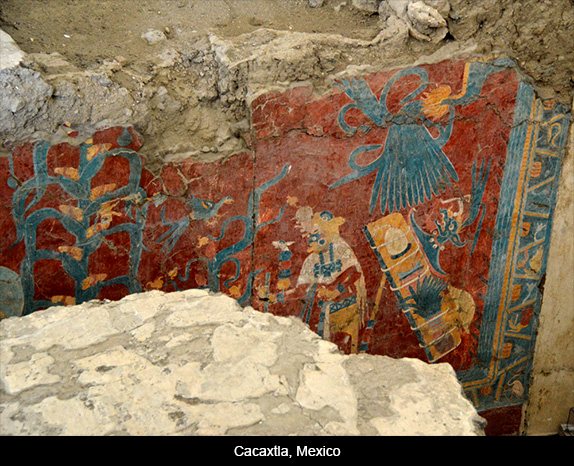

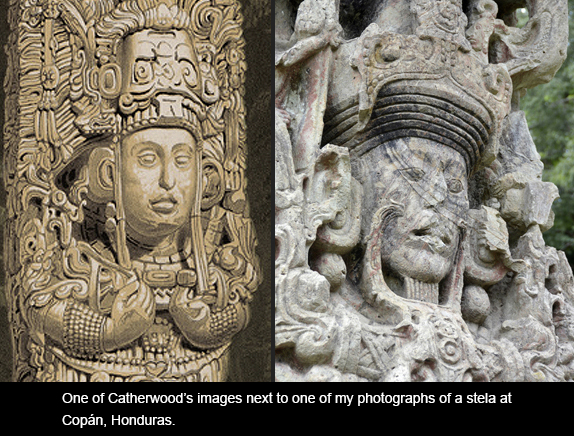

In The Catherwood Project, Katz references work by travel writer John Lloyd Stephens and artist Frederick Catherwood 150 years earlier. The two men met in Europe in 1836, and read an account of the Maya ruins at Copán (Honduras) by Juan Galindo. They decided to visit Central America themselves, with an eye to producing a more detailed and better-illustrated account. Their expedition came together in 1839 and continued through the following year. They visited and documented dozens of ruins, cataloging many for the first time. Stephens wrote about what they saw, while Catherwood made detailed drawings later rendered as steel engravings. His insight and accuracy allowed him to produce a sensitive visual record that remains immensely valuable.

Stephens and Catherwood were inspired by such as Galindo and Alexander von Humboldt. They, in turn, influenced Edgard Allan Poe. So they were involved, perhaps less consciously, in the practice of seeing and giving that Katz continues in our time. They were credited with “rediscovering” the Maya civilization. Their work resulted in several books, including Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan (1841). They returned for more exploration in 1843. Their relationship was clearly magical and very productive. Sadly, both men died young.

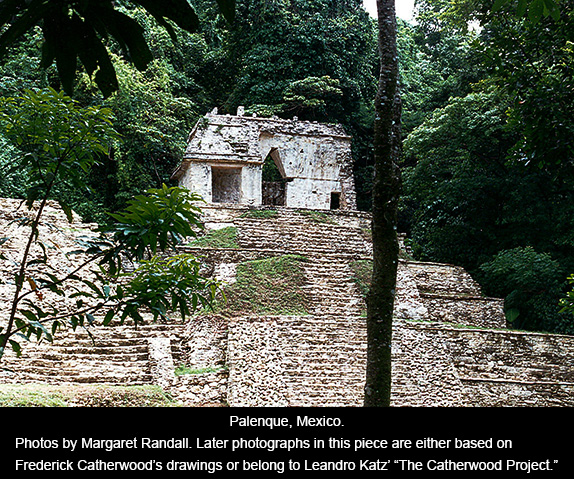

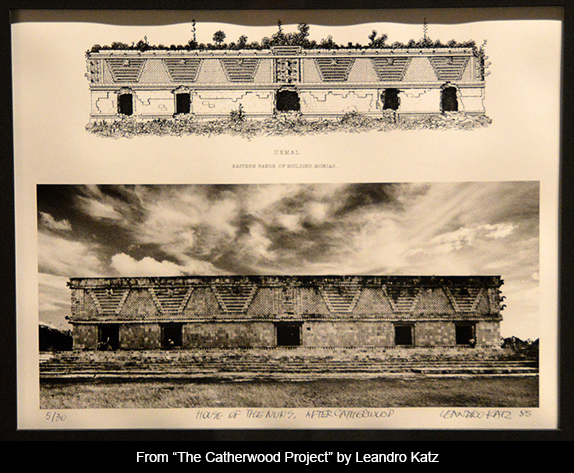

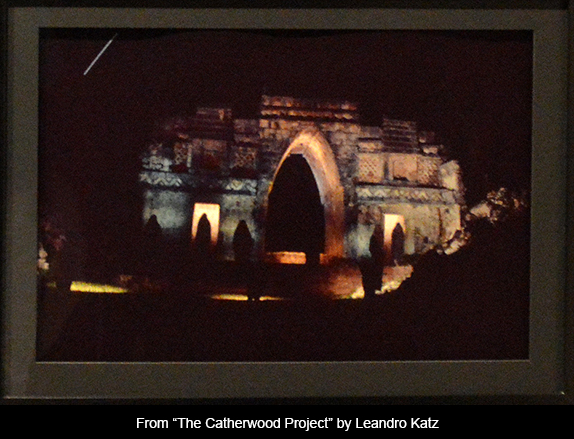

So many years later, Katz has used the products of this fecund relationship as the basis of his own artistic inquiry. “During the summer of 1984,” he writes “I had the opportunity to work in the Yucatan area, photographing the Maya sites drawn by Catherwood.” Much like projects such as Grand Canyon, a Century of Change: Rephotography of the 1889-1890 Stanton Expedition, Katz sought identical positions and angles used by Catherwood when he made his camera lucida drawings. “In this way, I started to compile the elements of a work-in-progress called “The Catherwood Project,” a visual reconstruction of Stephens and Catherwood’s expeditions.” Katz continued this work into 1986, covering other sites in the Yucatan and Chiapas regions, and finally completing his predecessors’ itineraries by photographing at Quiriguá (Guatemala) and Copán (Honduras).

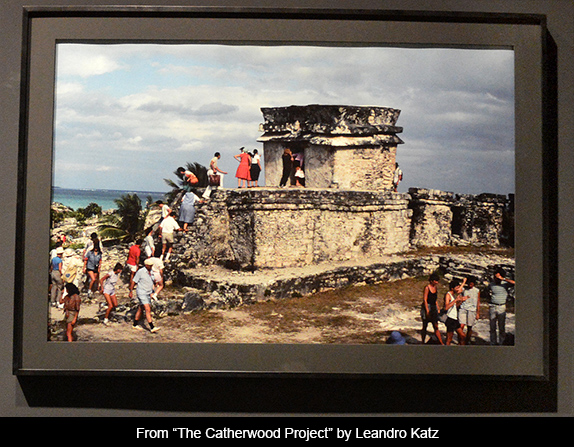

But while the Grand Canyon project documented science, Katz’ is emotional, political, and possessed of meaning often only possible in art. He has explained that his “Intention when starting The Catherwood Project, which resulted in nearly 4,000 black and white photographs and 1,800 color, was not only to re-appropriate these images from the colonial period, but also to visually verify the results of archaeological restorations, the passage of time, and the changes in environment,” all elements acquiring an added significance—indeed an urgency—as humans finally begin to recognize our environmental and sociopolitical impact on the earth. As Katz says: “In this ‘truth effect’ process, issues having to do with colonialist/neocolonialist representation become more central.”

Katz writes that in the process of covering the itinerary of the Stephens and Catherwood expeditions, he “became aware of Catherwood’s struggle to depart from his Eurocentric style . . . previous explorers could only manage to document the sites by merely reproducing the style and the vision of the Romantic period, the line in their drawings was wrong, their final results a fiction . . . [Catherwood] managed to enter the mind of the Maya architects, challenging his own Western hegemony.”

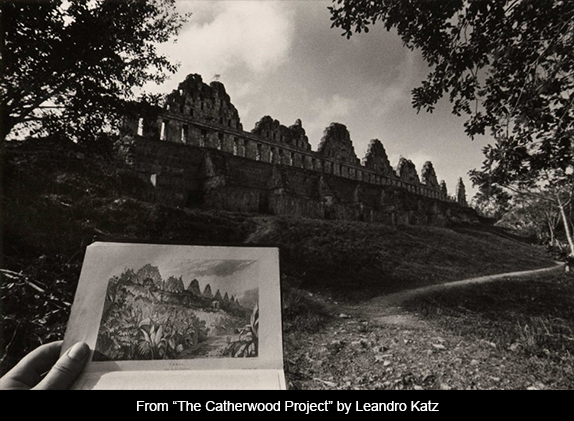

Katz describes three different approaches used to produce the works in this project: attempting to adopt as closely as possible the same points of view used by Catherwood, which at times included lower or elevated perspectives, often incorporating a view of his own hand holding Catherwood’s published engraving in front of the documented monument (making the comparison the subject of a single photograph), and following Catherwood’s vision of the site directly and without visual quotation: “At this stage, although the original structure is still being followed, the conceptual rigor of the project becomes more abstract.”

The Catherwood Project is only very partially represented in Unsettled Landscapes. One of its most complete exhibitions was presented in Two Projects / A Decade (1996, El Museo del Barrio, New York City). What we see in Santa Fe, however, is profound in its impact. Sophisticated curating (elegant placement against black walls in a darkened space) perfectly presents Katz’ vision and what it means in terms of exploring time. We grasp what Catherwood did 150 years ago, how Katz appropriated the earlier artist’s struggle, and what places such as Palenque, Tulúm and Copán tell us about our contemporary world. One of the latter images leaves Catherwood behind, and is a color photograph of one of the ruins today overrun by brightly and sometimes scantily dressed tourists who trod its delicate walls.

SITE Santa Fe (1606 Paseo de Peralta, Santa Fe) is, without a doubt, one of the preeminent art spaces in New Mexico. Since its founding in 1995, the institution has presented more than 80 exhibitions of uniform high quality, including eight biennials and works by over 500 artists from around the world. SITE also offers ongoing educations, outreach, and multidisciplinary programs. The spacious exhibition halls are open Thursday and Saturday from 10 to 5, Friday from 10 to 7, and Sunday from 12 noon to 5. They are closed Monday and Tuesday, free all day Friday and Saturday from 10 to 12 in conjunction with the Santa Fe Farmers Market. Admission on non-free days are $10, $5 for students, teachers and seniors, and free for members. For those of us who periodically fork over $25 to visit New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the entrance fee seems like a bargain.

The current show, Unsettled Landscapes, opened on July 20, 2014 and runs through January 11, 2015. Gallery literature describes this group offering as a “look to the urgencies, political conditions and historical narratives that inform the work of contemporary artists across the Americas—from Nunavut to Tierra del Fuego. Through three themes—landscape, territory and trade—this exhibition will illuminate the interconnections between representations of the land, movement across the land, and economies and resources derived from the land.”

Responses to “SITE Santa Fe’s “Unsettled Landscapes” and “The Catherwood Project””