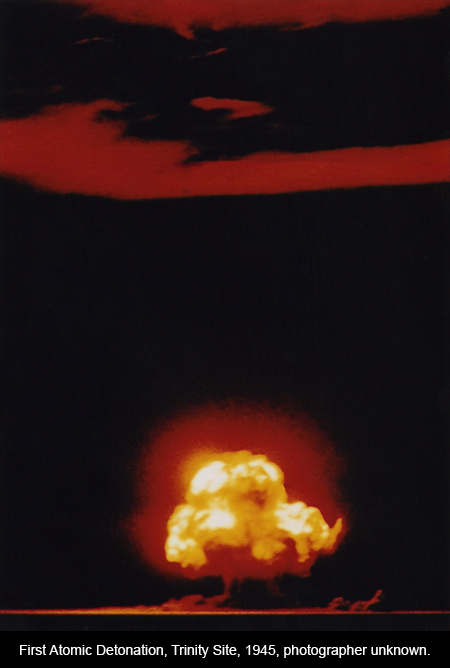

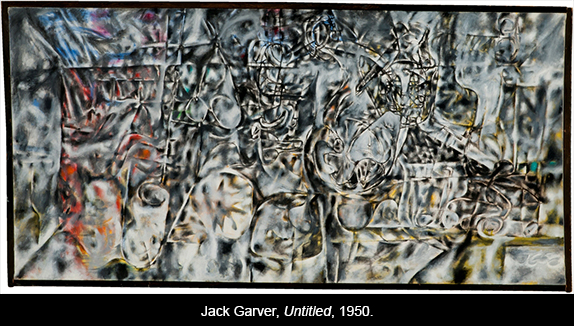

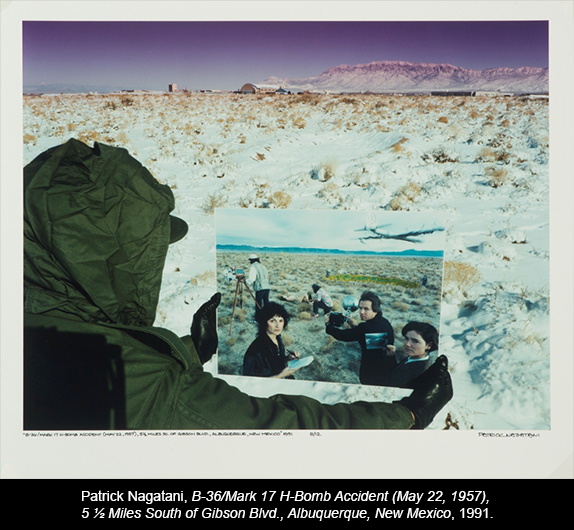

Visitors entering Visualizing Albuquerque, the massive survey exhibition at the Albuquerque Museum, are confronted with a big color photo of the first atomic detonation at the Trinity test site in 1945. Blown up to the size of a large Rothko painting, it is allowed to usurp the place of art. It dwarfs the Jack Garver painting hanging beside it, relegates Patrick Nagatani’s staged photo of nuclear winter to a footnote position, and announces that this is a show with an agenda, in which curatorial ideas and attitudes will take precedence over the actual art on display. It’s completely over the top as a piece of signage, meant to mark a turning point in human events and technological development that would change the course of the city’s history. Everything in the exhibit, all pieces of art large and small, will be subject to the fall-out of that arresting image.

I was grateful to see Margaret Randall’s skeptical reaction to this conceit in her recent Mercury review of Visualizing Albuquerque. Having grown up in Albuquerque during the 1940s and 50s, Margaret knows aspects of the city’s mid-century art scene better than anyone. She has a more balanced view of what’s important in local history, and it’s good to read her observations from personal experience and her notation of the many significant artists who were active in the 1950s and were somehow overlooked by the curator in both the exhibition’s survey and its accompanying book.

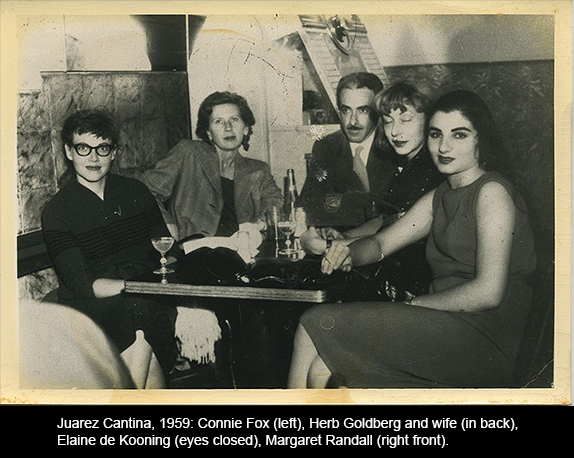

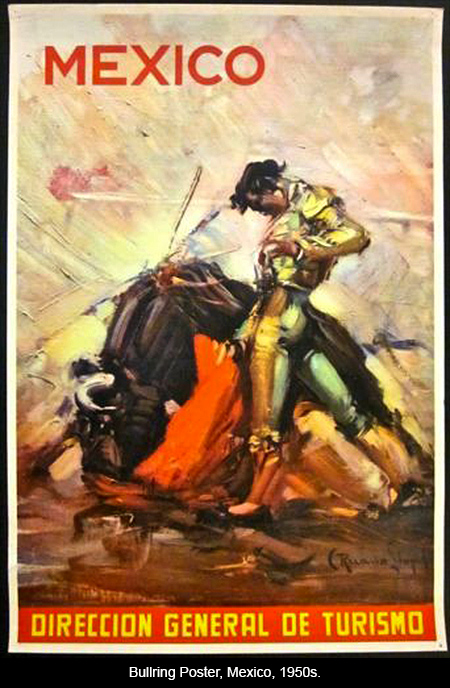

In Part I of these notes, I tried to offer my impressions of the art scene that I witnessed in the 1970s and 80s, a period that now seems to me to have been a kind of Renaissance or Golden Age for art in the city. But that great flowering had been prepared by the heroic generation that Margaret knew in the 1950s, and by the expanding influence of international Modernism that Clinton Adams and Van Deren Coke promoted at the University of New Mexico in the 1960s. Shortly after the opening of Visualizing Albuquerque, as I was doing some research on the mid-century era, I ran across the photo below of the young Margaret (on the right), seated at a Juarez cantina after a day at the bullfights with painter Connie Fox (left), sculptor Herb Goldberg and his wife (in back), and the New York painter and writer Elaine de Kooning (eyes closed), who was a visiting professor at the UNM art department at the time. After that trip to Juarez, de Kooning began her vigorous series of bullfight paintings, whose Abstract-Expressionist brushwork owes perhaps as much to the popular bull-ring posters of the day as it does to the violent drama, color and pageantry of the event.

Although there is much that is problematic about the exhibit, Visualizing Albuquerque has nevertheless been received as a welcome and long overdue opportunity to honor the contribution of the city’s artists. On view only through May 3, it forms the centerpiece of a citywide celebration of the arts this spring dubbed On the Map: Unfolding Albuquerque Art + Design, which continues through June and has stirred much excitement in the community. Some of the show’s shortcomings are compensated by other venues around town, such as the University Art Museum, where an exhibit of Jonathan and Faye Abrams’ donations offers alternative examples of work by several artists, and in the basement where there’s a range of Raymond Jonson’s post-1940s work and an alcove stocked with mid-century pieces by Jonson’s students and associates.

Visualizing Albuquerque seeks to provide a broad overview of art produced in the city, drawn almost entirely from the Museum’s permanent collection. This, in itself, is cause for celebration, since we voters can be justly proud of having supported the bond issues that made possible both the existence of the Museum and the enhancement of its holdings. In many ways, the show is also a tribute to the dedication of the Museum’s former longtime director, James Moore, and former curator of art, Ellen Landis, who were largely responsible for strides made in building the collection during the 1980s and 90s. Their efforts, together with the great generosity of community members who have donated art works over the years, made an enormous contribution to the quality and stature of the community’s showplace.

At this time of celebration, however, it’s important for all of us in the art community to voice our support for the Museum. It is seriously underfunded and undervalued by the present city administration, and budgetary constraints can unfortunately be felt in the show. There are puzzling discrepancies between works reproduced in the catalog and what’s actually on the walls, and you get a sense that there was simply not enough funding or room to accommodate the show’s ambition.

But the show also offers a chance to take stock of the Museum’s collection, to applaud its strengths and to observe what gaps still need to be filled to adequately represent the history of art in the city and the region. It’s wonderful to see, for example, the new acquisition of Mildred Murphey’s cast-aluminum sculpture in the Art Deco “style moderne” of the 1930s, which puts a new face on that era of the city’s art. Yet, as Margaret points out, there are so many omissions. In addition to the leading artists she names from the 1950s, I wonder where are such important figures of the 1970s and 80s as Terry Conway, Susan Linnell, Reg Loving, Russell Adams, Ken Saville, Bill Masterson, Tina Fuentes, Susan Wing, and Nancy Kozikowski? And what about the many historical figures, Brice Sewell and Loren Mozley, for example, who were associated with both UNM and the WPA projects of the 1930s, and also Velino Shije Herrera of Zia Pueblo, who recreated the kiva murals at Coronado Monument for the WPA and taught at the Albuquerque Indian School (and who may even have produced the original design of the sun symbol on the State flag)? Are these and so many other artists missing because there’s no adequate example of their work represented in the collection? And even if so, don’t they deserve at least a mention in the catalog’s narrative overview?

In many ways, Visualizing Albuquerque can be seen as a response to Van Deren Coke’s pioneering exhibition Taos and Santa Fe: The Artist’s Environment, 1882 – 1942, which was the show that inaugurated the new Art Museum at the University of New Mexico in 1963 and was the first attempt at a coherent survey of art produced in New Mexico. Albuquerque did not figure in Coke’s title and was barely mentioned at all in the comprehensive book that accompanied the exhibit. So it’s understandable that the Albuquerque Museum might want to mount a show to address this omission—and, while trying to account for its absence, to also demonstrate that at the very moment when Coke’s show opened, the city’s art scene was undergoing changes that would alter the perception of Albuquerque’s position in the art world.

A problem with Visualizing Albuquerque, however, is that, unlike Coke’s UNM exhibition, it was not initiated as a scholarly inquiry. Coke and his graduate students were doing groundwork research where none had been done before. No one had tried to produce a survey of New Mexico art, or to track down the factual record and account for the contributions of its many participants, much less to put the art in historical perspective and trace the connections of those artists to the art schools and prevailing artistic trends of the time. By contrast, Visualizing Albuquerque feels more freely cobbled together out of the Museum’s vaults, guided by little more than a sense of civic obligation to the community to put up a comprehensive show acknowledging the independent spirit of its art in all its eclectic variety.

It might have been better for the Museum to have curated the show internally. We need for fresh eyes to look over this material. Having already produced two major exhibitions surveying the history of New Mexico art at the Museum of Art in Santa Fe, together with two accompanying full-length books, retired curator Joseph Traugott is clearly bored with the subject and has done little more than follow his previous formulas in How the West Is One (2007) and New Mexico Art Through Time (2012). He’s shown little interest in exploring the actual factors that have made Albuquerque’s art different from the better-known art of the early colonies of Taos and Santa Fe. The catalog is riddled with errors and oversights.

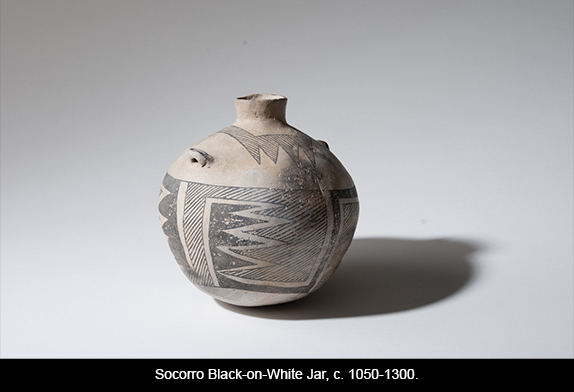

By utilizing objects in the Museum’s historical collection as well, Visualizing Albuquerque attempts to place the city’s art within an enlarged, multicultural historical context that encompasses the entire middle Rio Grande region and stretches back to its earliest inhabitants. But the odd assortment of pre-1945 historical materials tends to be the show’s weakest aspect. Rather haphazardly selected, they seem to be mostly ciphers in a spotty and often misleading back-story narrative that finally seems quite pointless.

If the purpose of the show is to celebrate Albuquerque’s artists and the extraordinary art scene that developed here after the arrival of full-fledged modernism in the mid-twentieth century, then I question the necessity of the historical survey—bombs and all. A profound and fundamental change occurred internationally in the art world at mid-century, which basically made the previous historical approaches to art-making irrelevant—especially the romantically picturesque and modernist-inflected easel paintings of the early Taos and Santa Fe artists. (See my Mercury article on the early work of Agnes Martin.) The whole idea of what art can be, how it is practiced and how it relates to the viewer, came under reconsideration. Without acknowledging that fact, and recognizing its historical link to the evolution of a fully cosmopolitan mentality steeped in an enlarged self-consciousness about the entire human enterprise of art-making, it’s not going to be possible to come to terms with contemporary art. And it’s totally bogus to suggest that a bunch of “Californians” came to town, hooked up with the University, and made things different. No, I have to question the application of Traugott’s formula for “14,000 years of art in New Mexico” and even the most fundamental principle of art around which it has been built.

Moving through the exhibit’s initial historical gauntlet, some viewers will be puzzled by wall labels that tell them, for example, that a Folsom projectile point or a metal Spanish crossbow tip is the work of an “Unidentified artist.” Soon they’ll realize that “artist’s licenses” are being rather freely issued here, to a point where one wall sign near the end of the exhibit announces that “We’re All Artists.” (This chummy and flattering sentiment is given full rein in a back room where visitors are encouraged to make self-portraits and view themselves as a work of art.) But even Josef Beuys, who seemed to espouse this idea in the 1970s, made it clear that only potentially are we all artists. Being an artist will require a change of consciousness, a heightened awareness of self and world. And a change of consciousness, of course, is ultimately what all artists hope to effect in viewers of their work.

As viewers turn the corner to exit the corridor of historical materials, they encounter what is to my eye the most egregious misstep in the show. Here, blocking any alternate turn and taking up altogether too much room in an already crowded exhibit, is a bright, shiny, red Model T speedster. Assuming it to be part of historical Albuquerque, at first we might think it’s the expensive toy of the grown-up son of Francisco and Margarita Armijo y Otero, whose oversize 1906 portrait, proclaiming their material success, we have just seen. But its presence in the exhibit is only explained in remarks in the catalog introduction, and it points to a serious problem in the curator’s rationale.

“Art is a slippery term to define,” he tells us, “especially in New Mexico where diverse cultures have merged while simultaneously maintaining their individual integrity. In this social context, a work of art is an aestheticized object. This definition challenges the idea that only artists make art. As Marcel Duchamp demonstrated almost a century ago, anyone can aestheticize an object by changing its cultural context or by interpreting it in an aesthetic manner.”

Leaving aside the fact that Duchamp denied that there was any “aesthetic” consideration involved in his choice of what he called a “readymade” (a manufactured object not fashioned by the artist’s hand but simply selected to be regarded in an art context as a matter of provocation), it’s a grave mistake to call a work of art “an aestheticized object.”

The curator voices his impatience with art world terminology, which he apparently feels is too constraining and perhaps outmoded. “Most art terms were conceived as either-or propositions; it’s fine art, or craft, or popular culture, but not all of these together,” we’re told. “This study interprets objects made in and around Albuquerque from multiple perspectives and uses multiple terms to describe individual objects. A good example of this concept is the Ford Model T speedster. It is material culture, but it was altered into the speedster format and now can be considered as art, craft, design, documentary photography [?], folk art, kitsch, and popular culture. The speedster also falls into the ‘I don’t know’ category: ‘I don’t know what art is, but I know it when I see it, and this is art to me.’”

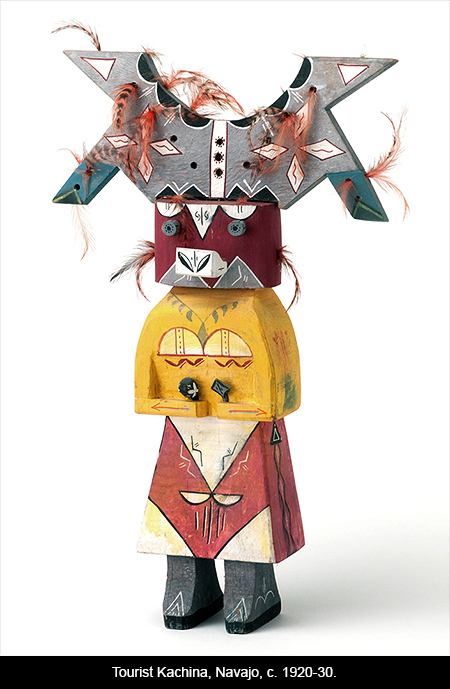

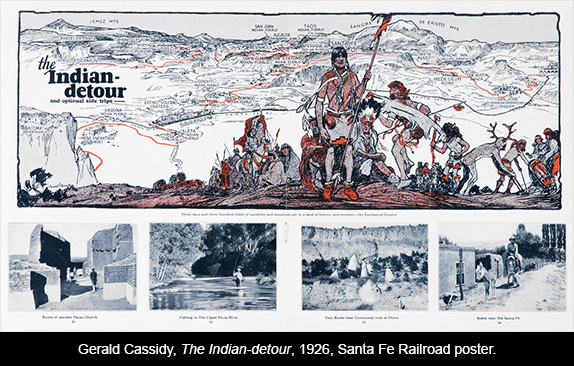

This may sound like a capitulation of any responsibility for discernment, dangerously close to the common philistine statement, “I don’t know anything about art, but I know what I like.” It’s not helpful to issue that kind of license to the exhibition’s viewers, and leaves them incapable of meeting the challenges posed by contemporary art. Yet he’s grasping for some way to allow respectful consideration for such objects as Clovis points, Pueblo pottery, Navajo jewelry, Hispanic colchas, tourist kachinas, and Santa Fe Railroad posters, as well as such recent postmodernist genre-bending efforts as Deana McGuffin’s designer cowboy boots, or Thomas Barrow’s chair encrusted with toy cars, or Ursula Coyote’s production still from Breaking Bad, or John G. Garrett’s silly wire curtain of strung-together beads and candy-colored plastic, like a Hobby Lobby mock-up of a Jackson Pollock painting. The postmodernist works, however, traffic in a self-conscious irony that sets them apart from the other historic objects, which are mainly craft objects having greater or lesser amounts of artistry.

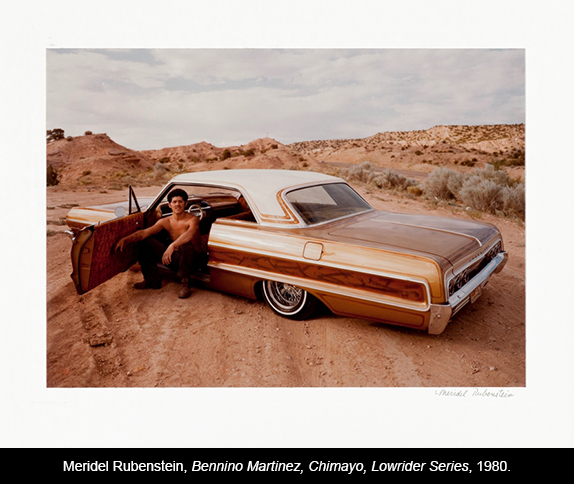

The inclusion of the speedster might have made more sense if it had been paired with an example of a vehicle modified into a Lowrider. Here’s an art form steeped in irony that has been brilliantly practiced locally and its inclusion would have allowed not only a better understanding of the possibilities of art, but also a better acknowledgement of the Latino community’s contribution.

We do use the term “art” for a certain kind of skill tradition—the art of embroidery; the art of tightrope walking; the art of negotiation. And, at its base, art is tied up with the way of doing something. Marshall McLuhan, the popular media analyst of the 1960s, was fond of pointing out that the Balinese, who have maintained one of the most elaborately integrated cultures on the planet, have a saying: “We have no art; we do everything as well as we can.” This attitude used to be found in tribal societies throughout the world, and it is clearly evident in traditional Pueblo culture. No one would deny that the painting on a Pueblo pot can transform a functional object into a work of art, providing an element of spiritual harmony to daily life. And no one can deny that both access to manufactured goods and the appetite of the tourist market have transformed this once-integral activity into a hybrid form. As such, it has the potential for either a serious and highly refined expressive mutation of tradition (just like any other art), or it can be an opportunity to produce a cheap knock-off of standard design (like any production work out for a buck).

I agree with Margaret that there’s a problem with Traugott’s claim that: “The first works of art produced in Albuquerque were spear points made by Paleo-Indians known as the Clovis culture, followed by the Folsom culture. […] Obviously these spear points are material culture, but they are also works of art because their makers aestheticized them in multiple ways.” It’s impossible to know what factors were at work in so distant a culture, but however beautiful—and beautifully executed—a Clovis point may appear to our eyes (“a perfect blend of form and function”), it is not necessarily a work of art. It is first and foremost a piece of technology, a finely wrought example of what the Greeks called techne, skilled know-how, applied to producing a functional object, a device for killing. Despite its beauty, it is not an example of what the Greeks called poein (source of our word “poetry”), the innovative creation of something with an independent existence, which honors the gods (i.e., forces shaping the world, which exist beyond the mortal comings and goings of the human) and honors the human capacity for invention, for bringing forth something that adds a new dimension of signification to the world. If it could be shown that the maker intended to apply his concentration and skill not only to improve functionality, but to infuse his work with spiritual grace, so that its perfection would enlist the aid of the supernatural in achieving a successful kill, then it might be just possible to call it a work of art.

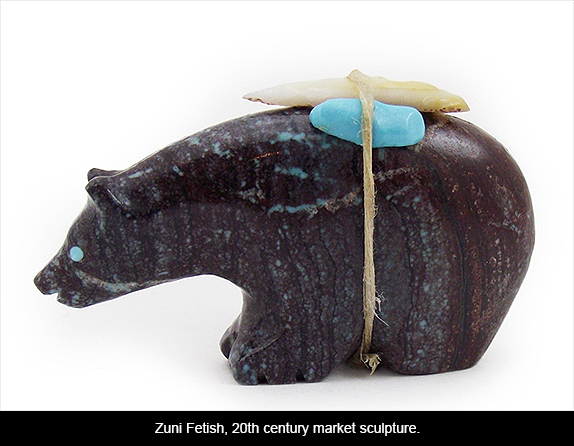

On the other hand, I would argue that a tiny “micro” point that I found in the region of Chaco Canyon, which is clearly too small to be functional (less than ¾”), can only be a work of art. Smaller than a so-called “bird point” (a misnomer for a point whose smallness allows exceptional penetration), and made many millennia later than the Clovis or Folsom points, it is a deliberately produced replica of an object central to the act of killing. As a vital necessity for the survival for the community, success in the enterprise of hunting requires all the psychological energy that can be mustered on its behalf. My sense is that the tiny point was produced as a kind of amulet, a token invoking the aid of supernatural forces against the world’s unpredictability, and beseeching an understanding of the vulnerability of the hunter and the human community, which requires the taking of a life to feed itself and to ensure its own continuity. And this aspect of reparation would be of even greater urgency if the object is meant to be related to warfare. As such, the little point may have been intended as an offering. Or it may have been a component of a personal “medicine pouch,” or perhaps part of an assembly like a modern Zuni “fetish” carving, which, although made for a tourist market, has an ancient sacred form as its prototype.

What sets a work of art apart from tools and technology is that it is not an object of use. It is made on purpose, but it is not meant to be a part of active, instrumental life. It remains in the realm of contemplation.

We homo sapiens sapiens have the most sophisticated and complex brains on the planet. Our brains are wired with extraordinary channels of feedback—we are constantly learning and adjusting, working with the input of our senses and filtering it through past experiences, projecting its possible application in the future. Most of life is involved with and taken up by direct action and interaction, with getting things done. When we confront a situation we have to decide what’s the best possible/feasible action to take: is it to be fight or flight? But there’s a secondary component to our lives, which is the imaginative or contemplative side. It’s that time when we disengage from direct action and think about it, go over it imaginatively, reminisce about the past, reconsider and evaluate past actions in order to entertain possible plans for the future, and we project forward, letting our minds roll on. We play things out in imagination. Our brains are actually physiologically programmed to do this—and they do it automatically during the one-third of our lives that we spend in sleep, when our minds engage in dreamwork. When we do this consciously, however, we call it contemplation. All art derives from, operates within, and remains to be dealt with in the region of contemplation.

Notice that the word “temple” occupies the center of the word “contemplation.” In our culture, where we assume we have little time for contemplation, art is set aside from the workaday world in temples that we call museums. This is not necessarily the case in other cultures, but it is what we mean by calling art a “leisure-time activity.” Work, which is a form of action, is undertaken in order to provide for and sustain life. Work is what we do out of necessity. In regard to life’s necessities, art has no practical use. It belongs to leisure, to the time not devoted to work, but which is set aside to leave us free to engage with the world (the world as such), and to do so unmotivated by our personal needs. It means approaching the world from a different angle, no longer intent on looting it to fulfill some physical need. The problem with our culture, however, is that we are mostly afraid to face the world as such. We usually feel we must fill leisure time with something else—the distractions of entertainment.

Let’s get clear on what’s at stake by going back to the Model T speedster. Elsewhere in the exhibition catalog it is pointed out that the speedster’s apparent “customizing” was done with a commercial kit, supplied by the Ford Motor Company to interested consumers. While the automobile is undeniably beautiful and has been lovingly maintained, it is nevertheless the product of a hobbyist following a supplied means for modifying his vehicle to improve its looks and performance. It is truly an “aestheticized object.” But it is not a work of art. You might as well include a “paint-by-numbers” picture in the show, surrounded by a nice handmade frame. There is a fundamental difference between creation and what is best referred to as recreation. To deny that difference is disrespectful, not only of the artists in this show, but of the whole basis of art and the place of its meaning in human life.

Creativity involves bringing something new into being that did not exist before. The impulse behind making a work of art is exactly the opposite of the rationale of the mountaineer, who claims to climb a mountain “Because it’s THERE.” An artist makes art “Because it’s NOT THERE.” It’s done in answer to a felt deficiency, something that requires expression. Art comes about through dissatisfaction with the given state of affairs; it’s a desire for renovation, for a fresh reconsideration of how things stand. Nevertheless, although art is expressive, it is not—at least not primarily—about communication. It’s about innovation and about making. It’s about engaging with the given world through selected materials, interacting with them imaginatively and to the best of your abilities, mustering all your concentration while maintaining openness to possibility and a sense of play. Through purposeful engagement with materials, you are searching for and originating form, both finding it and intending it. This is because art basically comes about through the discovery of relationships. “Likeness,” throughout the millennia, functioned as one of the more salient relationships explored by art, but the discovery of fresh metaphoric associations has always been at art’s core.

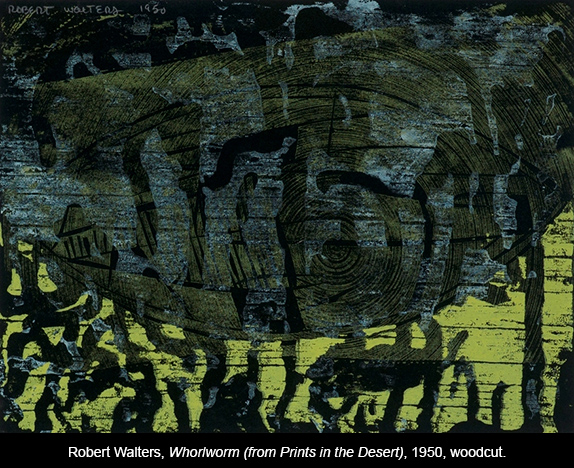

A lack of appreciation for the way artists interact with materials and engage the expressive possibilities of form during the creative process, puts the curator at a loss when it comes to discussing abstract art. Take his entry on Robert Walters’ color woodblock print from 1950 (an image which, unfortunately, is reproduced upside down in the catalog): “Robert Walters’ image Wormwood reflects his experiences as a frogman, a member of the Navy Underwater Demolition Team, in the Pacific during World War II. The image alludes to the underside of a wooden ship with seaweed rising up to meet the hull. The acidy yellow background reminds viewers of the sun shining through the cloudy water around a hull weakened by wormholes.” He talks about it as if it were a picture, adding biographical data and unfazed by the anachronism of suggesting that the hulls of WWII battleships were made of wood.

But Walters’ richly evocative image has nothing to do with picturing things in the usual sense. It is the product of his sensitivity to materials and their formal suggestiveness, and it has come about through his willingness to collaborate with nature in the artistic process. Working in the experimental atmosphere of Adja Yunker’s workshop, his decision to print directly from a piece of wood already textured by burrowing worms gives a whole new slant on the medium of “woodcut.” He contrasts this random spontaneity by inking a second board, whose raised pattern of circular and concentric growth rings expands regularly, like ripples in a pool, juxtaposing the order and disorder of nature’s moods. Printing with opaque inks on black paper, he achieves a brooding effect expressive of the dark intermingling of growth and decay. Yellow ink on black creates the effect of a sickly green, even though no green pigment is actually used.

And if only the actual title of the print had been Wormwood, it might have been possible to discover a range of expressive possibilities (perhaps even an apocalyptic bitterness) owing to the literary evocativeness of that word. But that title is a mistake (a mistake which, strangely, Traugott does not make in How the West Is One). Walters’ actual title is Whorlworm—still chosen for the metaphoric associations of spinning and destruction that might be triggered in the viewer’s imagination, augmenting the print’s visual poetry. With the proper title in mind, the curved lines, inscribed by the artist’s own hand, imply the shape of a leaf, rather than a presumed boat, as the target of the worm’s destructive attack, and its pestilence radiates outward. And yet all of this happens without the image becoming a picture. The artist simply invites the viewer to become engaged and join in the dynamic of the formative process, which is made to feel as if it were still ongoing before our eyes.

Another artist associated with Prints in the Desert and Yunkers’ experimental workshop in the 1950s was Frederick O’Hara, whose Koshare print is discussed as if it were a woodcut although it is a lithograph. Again, there is little understanding of the artist’s process, which involved spontaneously tossing an inked rag onto the stone and then developing the imagery from this accidental form. Elmer Schooley, who studied with O’Hara, explained his method: “He was real big on this business of listening to your material…. He would flow ink onto a stone and then see what kind of form it suggested, and then put it down and print something else on top of it.”

It was modernism’s emphasis on form and the material basis (basic materials) of each medium of art-making that led to the tremendous outpouring of creative engagement across all media—from painting and sculpture to ceramics and fiber arts—in Albuquerque, beginning in the 1950s and expanding through the next three decades. And it is the depth of involvement with form and materials that puts into question Joe Traugott’s unfortunate and misleading catalog definition that “art is an aestheticized object.”

April 22, 2015