Elaine de Kooning (1918-1989) was a great painter and brilliant writer about art. Her essays titled “So and So Paints a Picture” remain among the most insightful describing the art and process of a number of her contemporaries (I riff on these in my title). Elaine came to New Mexico in 1957-58, where she was a visiting professor in the University of New Mexico’s art department, and the light, space and colors of this place had a lasting impact on her work. She was also married to Willem de Kooning, perhaps the best known and most successful of the Abstract Expressionists or “Action Painters” who put a new US art on the world map at mid-20th century. Although separated for long periods, she returned to care for him in his later years. Unexpectedly, she died before he did. Because male artists were seen while their female counterparts were often ignored, his fame overshadowed hers.

The National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC takes an important step toward righting this great wrong with its exhibition Elaine de Kooning: Portraits. The show opened on March 12, 2015 and will be up through January 10, 2016. There are 66 paintings, ranging from intimate renderings of family and friends to many larger than life of the era’s most important writers, artists, sports and political figures—many of whom were also friends.

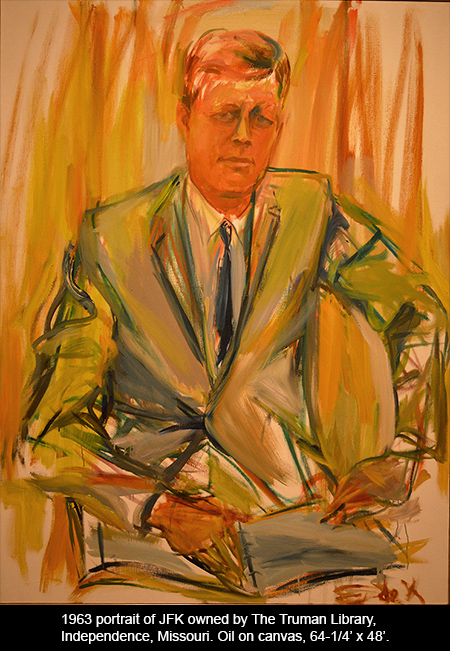

Elaine de Kooning is one of only two women commissioned to paint a sitting president of the United States. The Graham Gallery, where she showed at the time, suggested her name. Its owner, Robert C. Graham, received the sparse response: “Mrs. de Kooning is a painter acceptable to President Kennedy.” She produced hundreds of sketches and paintings of John F. Kennedy, all done in the year before and immediately after his death. Some of these images are enormous. “I worked on a ladder,” she explained, “and his feet were at my eye level.” Later she had to “bring him down to human size.” Kennedy’s and de Kooning’s shared Irish background may have been an element of connection. Elaine also mentioned daughter Caroline’s appearance at one of the sittings. The child asked: “How much paint do these tubes have anyway?” The artist looked up and saw that she had emptied a whole tube of yellow.

The presidential portrait chosen by the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri, is on loan for this show, as is the much larger full-length likeness owned by The Portrait Gallery. The exhibition catalog includes a touching photograph of Elaine in a bathing suit on the beach near where she painted the president, modeling Kennedy’s head in the sand.

It’s time for a disclaimer. Elaine de Kooning and I were friends. She was a great mentor to me, and in memory continues to be. We met during her time at UNM. I was an incipient poet, she already an accomplished painter. But I was able to introduce her to the bullfights in Ciudad Juárez, a subject she would paint for many years. I followed her back to New York (as did several others who knew her here) and we remained friends until her death. March 12th would have been Elaine’s 97th birthday. I wished this honoring of her work could have happened when she was alive, or that she might have lived to experience it.

If you love great painting, appreciate portraiture, and want the opportunity to experience one artist’s astonishing range, this is an exhibition not to be missed. Head curator Brandon Fortune and her staff did a magnificent job of enlisting the support of those who have always admired Elaine’s work (they are listed as “Elaine’s People”), gathering paintings from individual collectors and museums across the country, and curating them in such a way that historic and artistic information appear in tandem. Photographs of the artist at work and an excellent film in which she describes her process as she paints one of several portraits of fellow artist Aristodimos Kaldis add breadth and depth to the show.

Elaine de Kooning was born Elaine Fried into a working class Irish American family in New York City. In the year of her birth, 1918, US women didn’t yet have the right to vote. She quit Hunter College to go to art school and studied, among others, with Willem de Kooning, a young Dutch painter who had stowed away on a ship and disembarked in a city where other immigrant artists, such as Arshile Gorky, were struggling to create a genuinely American art. Elaine met De Kooning in 1938 and immediately decided he was the most important of these painters. She also decided they would marry, which they did in 1942.

The Second Wave of feminism wouldn’t explode on the scene for two or three decades. Elaine never called herself a feminist and didn’t like to be called a woman artist, but she was deeply cognizant of the ways in which women were kept down, and fiercely determined to make her mark. For her, as for so many strong creative women of her time, this meant doing more and doing it better. At the same time, she was generous and supportive of other female artists, and of all young artists independent of gender. There must be hundreds, maybe thousands, of younger artists who owe their careers to her mentorship. One of the things I learned from Elaine was to invest in the work of a struggling artist each time I sold one of my own photographs or earned royalties on my writing.

Although Elaine’s large body of work includes her famous bull series (later also the paintings she made after visiting the ancient cave paintings in southern France and northern Spain), the Bacchus series, even still life and landscape, portraiture was something she did from the beginning and it was prominent throughout her career. She loved the male body. Having known her, I understand why she would co-opt, to the extent possible at midcentury, the male tradition of painting portraits of women and turn that practice on its head. She was witty, playful, and raucous.

In the exhibition’s wonderful catalog book, Elaine de Kooning Portraits, Brandon Fortune quotes the artist telling scholar Ann Gibson in 1987, “[In the past] women painted women: [Elisabeth] Vigée Lebrun, Mary Cassatt, and so forth. And I thought, men always painted the opposite sex, and I wanted to paint men as sex objects.” Indeed, a number of Elaine’s men pose seated, their legs spread, and in some instances the eye is drawn directly to their genitals.

In 1975 Elaine told an interviewer: “For me, doing portraits is an addiction.” A few years later she told another:

“When I painted my seated men, I saw them as gyroscopes. Portraiture has always fascinated me because I love the particular gesture of a particular expression of stance… the instantaneous illumination that enables you to recognize your father or a friend three blocks away or, sitting in the bleachers to recognize the man at bat. Working on the figure, I wanted paint to sweep the figure through as feeling sweeps through. Then I wanted the paint to sweep the figure along with it…”

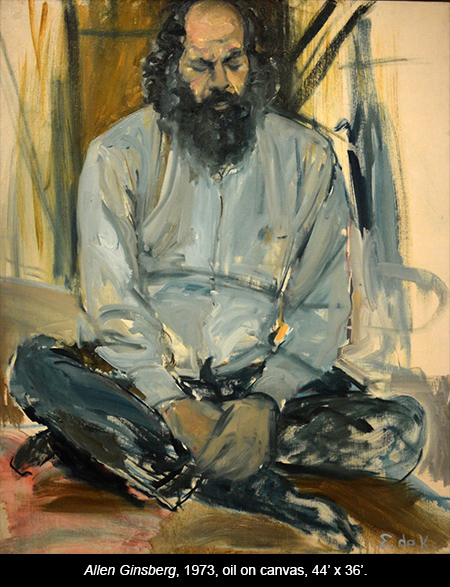

The show at the National Portrait Gallery includes portraits of Willem de Kooning, Fairfield Porter, Frank O’Hara, Harold Rosenberg, Robert de Niro, Leo Castelli, Megan Boyd, Denise Lassaw, Edwin Denby, Merce Cunningham, Patia Rosenberg, Ornette Coleman, the painter’s sister Marjorie Luyckx, Allen Ginsberg, Bernice Sobel, Donald Barthelme, John Ashbury, Larry Rivers, Brazilian soccer great Pele, Joop Sanders, Ethel Epstein, Rosalie Asher (the lawyer who tried but failed to save Caryl Chessman from execution—Elaine was vehemently against capital punishment), and of course President Kennedy among others. In some cases there are multiple drawings and paintings, through which the artist’s process and selection may be seen.

Native New Mexican artist Eddie Johnson appears beside New York artist Robert Corless in a large painting called The Loft Dwellers. The painting’s title evokes Elaine’s knowledge of the culture in which the New York artists lived at the time; most inhabited old industrial lofts. Eddie Johnson, who began by stretching canvases for Elaine here in Albuquerque, would become a fine artist in his own right. He was her assistant and photographer on the Kennedy commission. Johnson eventually returned to New Mexico, and died in Mountainair in 2012. Robert Corless also became a fine artist before his untimely death in a fire in 1979.

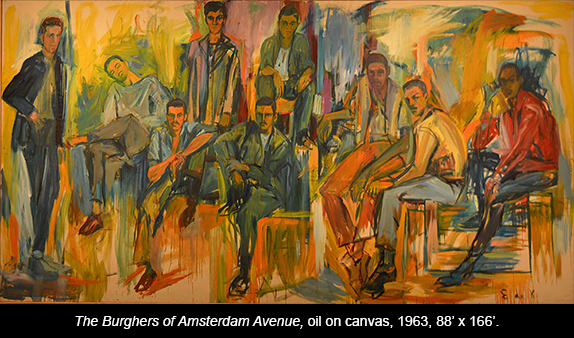

Many of these paintings are vast, their subjects appearing larger than life. A particularly impressive canvas is The Burghers of Amsterdam Avenue. Fourteen feet long, it had to be stretched in the museum. It depicts a group of nine young neighborhood men lounging in a variety of attitudes, and shows Elaine at her best in terms of her ability to render quick studies of all sorts of subjects. Art critic Tom Hess coined the phrase “body syntax” when speaking of the vivid likenesses she achieved in her portraits. There are also some beautiful self-portraits in this show, including several from Elaine’s earliest work.

Gesture is so well executed in Elaine’s portraits that in a number of them she deliberately erased some or all of the facial features. This is true in several images of the painter’s brother Conrad Fried, and of her fellow painter Fairfield Porter. An early critic, otherwise complimentary, wondered if she was unable to draw or paint faces. Nothing could be further from the truth, as many of her other portraits attest. But Elaine often said the face’s features change with age, while the way one sits, stands or moves is more of a constant throughout one’s life. Her figures often seem to be quiet and in movement simultaneously. One of the attributes of this exhibition is that a number of sketches and different versions of a particular subject are shown together, giving the viewer a glimpse of the artist’s progression and work method.

The gala opening of Elaine de Kooning: Portraits at The National Portrait Gallery in Washington featured music by the Bay Jazz Project and The Dolls. Museum director Kim Sajet spoke eloquently about the artist, correctly situating her in time and place and through a feminist lens. She also spoke of the risk the museum took in deciding to do this show. Elaine’s work, even today, hardly fits the conventional mold for which the nation’s official repository of portraiture has been known. And of course there’s the matter of this artist having been a woman. The museum did its decision proud. The event drew an appreciative crowd of 475. The following day, the exhibition’s curator Brandon Fortune told me it had gotten two million hits on social media!

For me, personally, the evening was a moving return to the decade of the 1950s, when Elaine de Kooning was among a handful of women painters—perhaps the greatest of them all—who overcame all obstacles but that of the marketplace to create important art. Women writers, singers, actors and those in other creative fields all shared this oppressive situation. I wandered the great room searching for the faces of Elaine’s nephews, niece and others I had known when they were toddlers. Finding those faces embedded in those of people who are now in their fifties or sixties was a challenge. I did so twice; both filled me with emotion.

A number of us, who were young or just starting out in the 1950s, were privileged to be at the opening. I photographed Denise Lassaw and Megan Boyd Chaskey standing by portraits Elaine painted of them many years before. My partner Barbara photographed me doing the same. Years have passed. We have all grown stronger. And we owe this in no small measure to Elaine de Kooning.

Responses to “Elaine de Kooning Paints a Portrait”