Visualizing Albuquerque is the comprehensive and extremely interesting exhibition currently on display at a number of city venues: The Albuquerque Museum, UNM Art Gallery, 516, Sixty-Six, and others. In this piece I will only address what is being shown in two Albuquerque Museum galleries, presenting a history of art in a city not traditionally known as an art mecca (in contrast with others such as Santa Fe and Taos). Painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, artist constructions, photography, weaving, tin and cabinet work, a tourist kachina (as opposed to authentic katsinas), woodcarving, jewelry, ceramics, maps, period advertising and promotional materials, architectural renderings, decorative playing cards, and public art are represented.

So are such dubious examples of art as 12,000-year-old Clovis and Folsom points, a musket ball from 1540, and a mattress cover from1800-1830. Joseph Traugott, one of the exhibition’s curators and the author of the exhibition catalog, Visualizing Albuquerque Art of Central New Mexico, contends that the “spear points are material culture artifacts, but they are also works of art because the makers aestheticized them in multiple ways.” He points to advanced technology and sophisticated chipping techniques as evidence of art.

I would argue that these objects certainly demonstrate craftsmanship and skill, but that art happens beyond the realm of utilitarian design. I wouldn’t call an Ancestral Puebloan mano and metate art, while the variety of decorated ceramics made by the same people certainly are. I also feel it is difficult, if not impossible, to ascribe the intentionality of art to people who lived so long and ago and left no record of how they saw what they created. We often call petroglyphs and pictographs rock art, with no knowledge of what such markings meant to those who made them. Were they signage, maps, symbols, instruction, art, or something else entirely?

While I appreciated the breadth of this exhibit, I balk at calling it all art. I also found several of the curators’ other affirmations confusing. For example, a piece called Untitled (Trinitite Souvenir), maker unknown, is an ink on paper drawing showing two small pieces of fused sand and the words “TRINITITE. This is sand almost instantaneously fused by terrific heat of the FIRST ATOMIC BOMB BLAST at Alamagordo, N. Mex. This material is slightly RADIO-ACTIVE but is perfectly safe to handle.” In the catalog Traugott writes: “As a work of art, this object renders frivolous and insignificant the most important event in New Mexico’s human history […] to see trinitite made into a tourist icon renders the event meaningless.”

I question the idea that the atomic test is the most important event in New Mexico’s human history. The most terrifying, yes, but important I don’t know. What of Don Juan de Oñate’s devastating arrival, the Pueblo Revolt, the building of great communities now buried beneath the earth, the acquisition through war of territory once belonging to Mexico, Route 66, or any one of a number of cultural or artistic moments such as the etching of 15,000 petroglyphs on the West Mesa, O’Keeffe in Abiquiu, or Lawrence in Taos? I find it as difficult to accept these fused pieces of sand as art as I do the Clovis spear tip.

Having said this, I admit there’s a fine, often fragile, line between the utilitarian and the artistic. Perhaps it is better to err on the side of inclusion, especially in a show such as this one, in which material culture goes a long way toward defining a place, its history, and the people whose visual record help us understand its changing face. I guess it is still an open question for me.

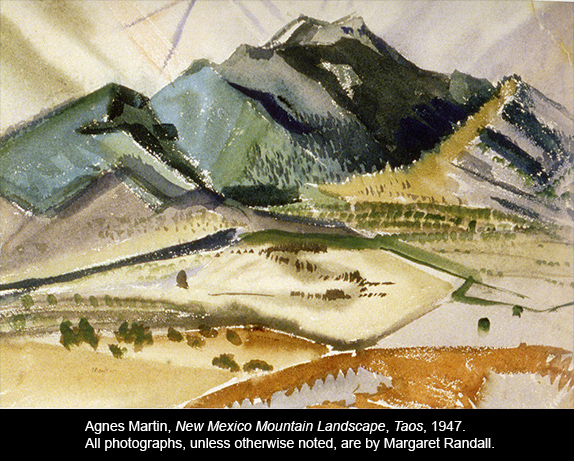

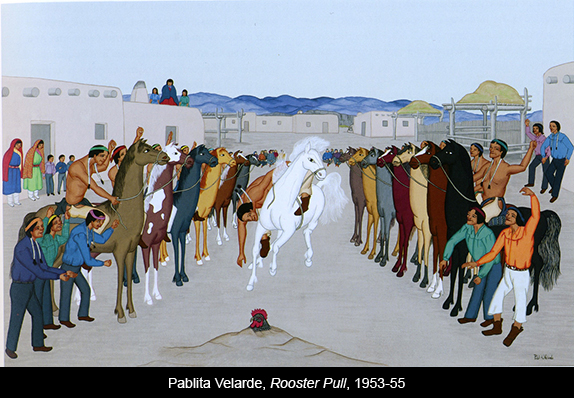

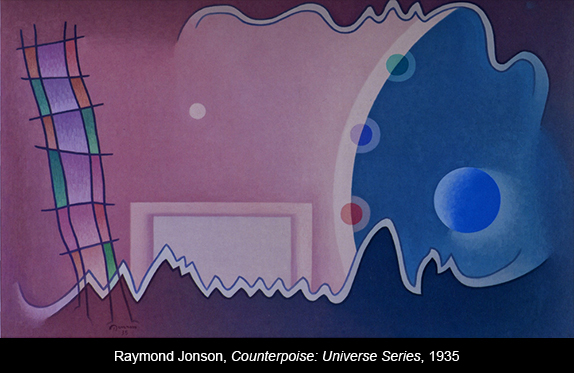

Overall, this exhibition is an exuberant experience: richly curated, well displayed, and full of powerful work. I loved the conversations between the variety of works, achieved by mixing genres and periods, and by not separating out indigenous artists or narrowly relegating styles. It was interesting, for example, to be able to view a painting by Pablita Velarde alongside a Richard Diebenkorn, Agnes Martin, Raymond Jonson, or Garo Antreasian. I liked seeing some large paintings hung unusually low on the wall. I felt I could walk right into them.

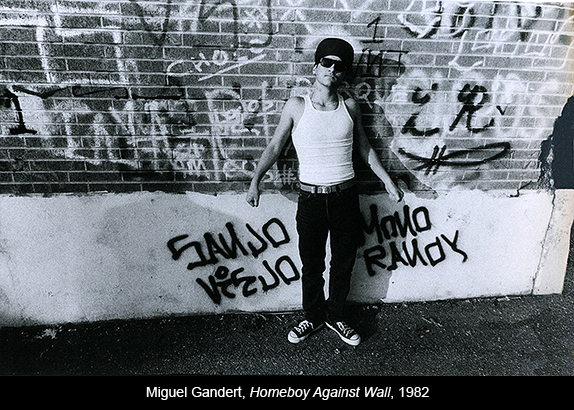

Photography is well represented. Gelatin silver prints and photogravures by Anne Noggle, Danny Lyon, Douglas Kent Hall, Joel-Peter Witkin, Meridel Rubenstein, Miguel Gandert, Wayne Lazorik, and Patrick Nagatani, among others, are impressive. Stephen Key McLellen’s photograph, Demolition of Alvarado Hotel (1970), documents a tragic history, while works by Edward Cherriff Curtis, the Cobb Studio, and a German lithographer who doctored a Rudolf Cronau scene are evidence of the ways in which misappropriation, colonialism and racism have so often defined cultures. Charles Fletcher Lummis’ Untitled (Penitente Crucifixion), taken in 1888, was a case of the photographer expressly defying the wishes of his subjects. Those staging the mock crucifixion asked him not to take pictures; he refused, literally at gunpoint. Inclusion of this unsettling image is one of many examples that make this exhibition so complex. There are also some prints by unidentified photographers, such as one taken during the 1970 political protest on the University of New Mexico campus. And some of the studio portraits go a long way toward evoking periods, social classes and cultures.

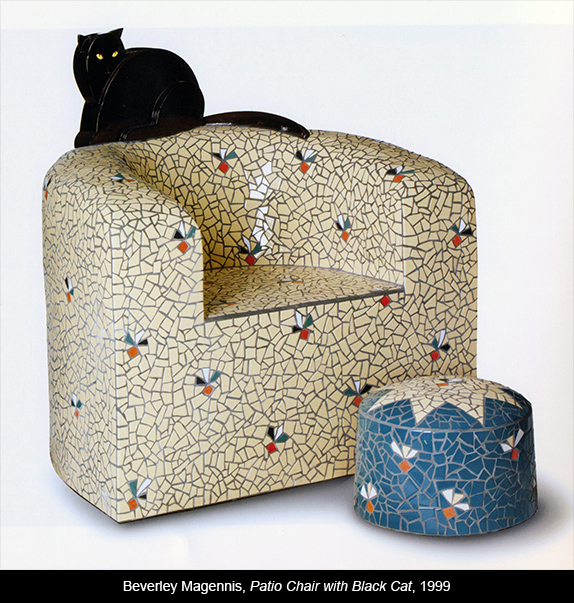

A sculpture by Deana McGuffin, depicting a pair of richly decorated leather cowboy boots, contrasts with Douglas Kent Hall’s black and white photograph of legs from the knee down wearing a variety of working cowboy boots; such counterpoint attests to the exhibition’s curatorial richness. Beverley Magennis’ Patio Chair with Black Cat a successful fusion of tile and architectural form, invites the visitor to “sit gently.”

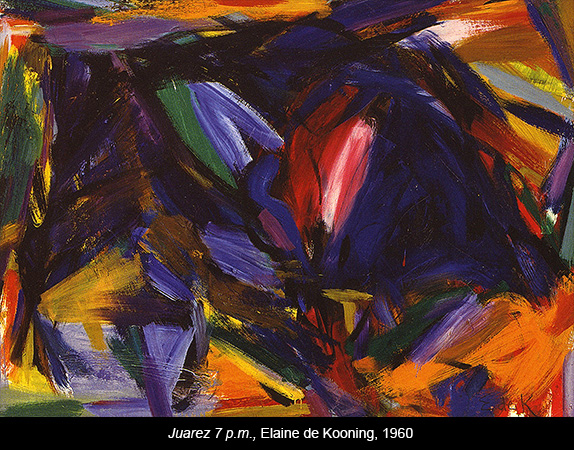

Some artists, such as immensely influential painter Raymond Jonson, are represented by more than one work. In several cases these are hung together; in others they are dispersed throughout the exhibition. Agnes Martin’s Taos Mountain is a painting worth viewing again and again. Prominently displayed is Elaine de Kooning’s Juárez 7 p.m., from the museum’s permanent collection. Its painterly surface explodes with movement and is one of my favorites. De Kooning, who taught in UNM’s art department in 1957-58, profoundly influenced Albuquerque artists here at the time.

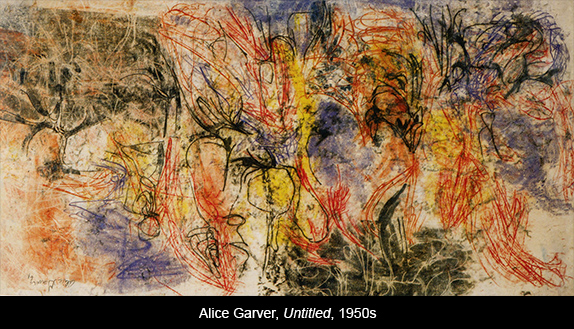

Alice Garver shows a large monoprint produced by a unique technique. As the work’s label explains: “Garver rolled a solid color onto the matrix and laid the paper on top of the ink. By drawing and pressing on the back of the paper she transferred loose, sketchy marks to the paper. By repeating this process over and over with multiple colors, Garver created highly energetic works at a huge scale for the period.”

Alice Garver was an important Albuquerque painter and printmaker who died in her early forties. At the height of her brief career, she painted murals on several floors of the First National Bank Building at San Mateo and Central. In an extension of her tragedy, these have long since been painted over. Not many of this artist’s works have survived, making the monoprint all the more appreciated. Alice’s husband, Jack, also died young and his work has become even less visible, so it was nice to see one by him as well.

I am particularly attentive to the paucity of work by women artists in museums in general and exhibitions like this one in particular. So it was wonderful to see women amply represented in Visualizing Albuquerque; not only the feminist icon Judy Chicago, the first recognized Native American woman painter Pablita Velarde, or well-known Georgia O’Keefe, Agnes Martin, Elaine de Kooning, Anne Noggle, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, and Lilly Fenichel, but many whose names are less familiar.

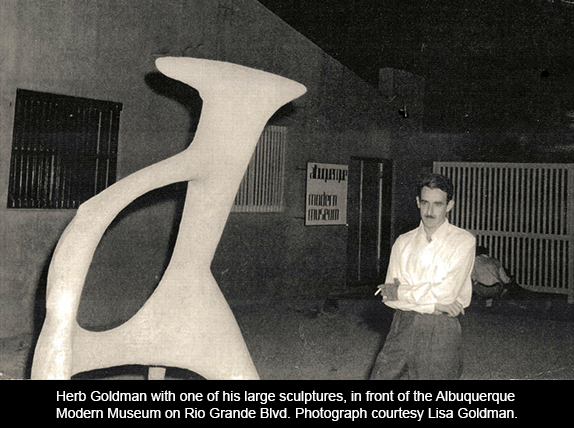

On the other hand, the omissions in this exhibition are startling. I realize that what to include depends on what may be available, curators’ tastes, funding, and other variables. But some of the most exciting artists of several important decades are absent from this exhibition: painters Harold Schleeter, Connie Fox, Richard Kurman, Don Ivers, Eddie Johnson, Bill Howard, Helen Hardin, Rita Deanin Abbey, Paul Harris, Robert Mallary, Joan Oppenheimer, and Rini Price; sculptors John Tatschl and Herb Goldman; potters Maria Martinez, Edwin Todd, and Maribel Todd; photographers Kirk Gittings and Cecilia Portal; architects Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter and Bainbridge Bunting, to name just a few. If these Albuquerque artists couldn’t be included on the museum walls, they should at least have been mentioned in the catalog.

And what about street art? And tattoo art? The Harwood Museum in Taos recently hosted a vast exhibition of these genres, which included several Albuquerque artists, not one of them referenced in Visualizing Albuquerque.

Among the absent is Herb Goldman. He was not only an Albuquerque sculptor whose work is known around the world, he was central to developing the city’s art scene in the 1940s and ‘50s. He led the small group that in the early fifties established the Albuquerque Modern Museum, located at 3800 Rio Grande Blvd. NW and precursor to our current art museum.[1] Goldman’s monumental pieces can still be viewed in Albuquerque and elsewhere. His unique sculptural house, The Henge, still stands in Roswell.

New York artist Elaine de Kooning, who was important in encouraging Albuquerque artists and bringing their work to the attention of those beyond New Mexico, wrote in a 1961 essay: “With few exceptions—Peter Hurd and Henrietta Wyeth in Roswell, Georgia O’Keeffe, Eliot and Aline Porter in Santa Fe, Agnes Martin, Beatrice Mandelman and Louis Ribak in Taos—the serious artists in New Mexico live and work in Albuquerque […] Some 20 excellent artists per 200,000 population is not merely a good percentage, it’s sensational in relation to other cities I have visited.” She goes on to talk about the fine artists on the faculty at the University of New Mexico, and adds: “Another special feature of the Albuquerque scene is the high percentage of women artists—about one-third—which situation doesn’t occur in any other city in the country except New York. Most impressive among these are Connie Fox and Joan Oppenheimer.” De Kooning also singles out Don Ivers, Bill Howard, Ralph Lewis, Richard Kurman and Jean Armistead.[2] In February of 1960, de Kooning organized a show of the work of 20 Albuquerque artists at The Great Jones Gallery in New York City, among them Connie Fox, Raymond Jonson, and Alice Garver.

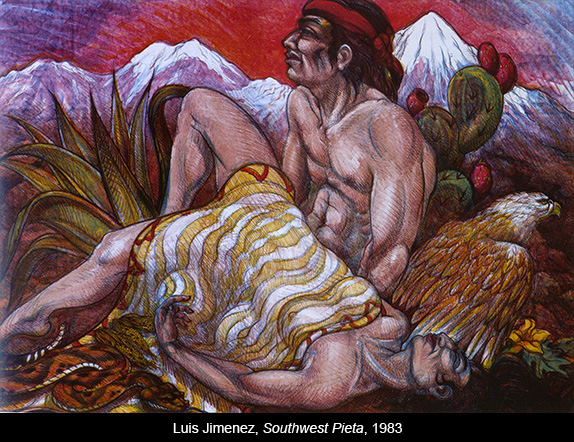

The inclusion of public art was gratifying in Visualizing Albuquerque, especially since there is such variety and high quality of it here. But I found the criteria and presentation both troubling. A couple of important public artists are represented with smaller pieces in the non-public art section of the exhibition, so perhaps the curators felt they covered them there. Still, rather than photos or small mock-ups, there might have been a video/slide show spooling on a giant screen to show the breadth and depth of public art in this city. Just a few examples of pieces by well-known artists that should have been included are: Nick Abdalla’s Don Quixote project, Nancy Kosikowsky’s large weaving at the Sunport, Beverley Magennis’ Tree of Life mosaic at Fourth and Montaño, Joan Weissman’s Nob Hill Gateway, Cultural Crossroads of the Americas by Bob Haozous at UNM’s Yale Park, and the River of Life by Sue Linnell on the west side. Again, this is a short list.

In conclusion, my caveats are personal, and not meant to discourage anyone from attending this exhibition, which is well worth seeing. It is beautifully displayed with a great deal of historical information. A number of artists are represented with major works, too often rare in a show of this type.

The ever-expanding Albuquerque Museum reaches out in new ways to present its holdings attractively. Even the museum shop has gotten a much-needed facelift; its book section is particularly satisfying. Price of admission, especially when compared with other museums, is ridiculously low: $4 for adults (with a $1 discount to New Mexico residents with photo ID), $2 for senior citizens sixty-five and over, and $1 for children 4-12. The first Wednesday of each month and Sundays from 9 to 1 p.m. are free to all. Parking is also free. Museum hours are 9 to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday.

I hope, as museum director Cathy Wright says in her catalog foreword: “This […] is a first stab at illuminating this fascinating history.” As anyone who lives in Albuquerque knows, especially those of us who have lived here much of our lives, other state artistic centers have nothing on this place in terms of its rich history of art.

Responses to “Visualizing Albuquerque”