Little is left of Agnes Martin’s early work. In 2012, the Harwood Museum in Taos gathered together what they could find and mounted Agnes Martin: Before the Grid, to honor the artist’s centennial year. After traveling to the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo, the show has come back to the University of New Mexico’s Jonson Gallery (through December 14) and is well worth a visit. It provides a rare glimpse into Martin’s apprentice years and serves as a reminder of the extraordinary vitality of the modern art scene in Albuquerque and Taos in the 1950s.

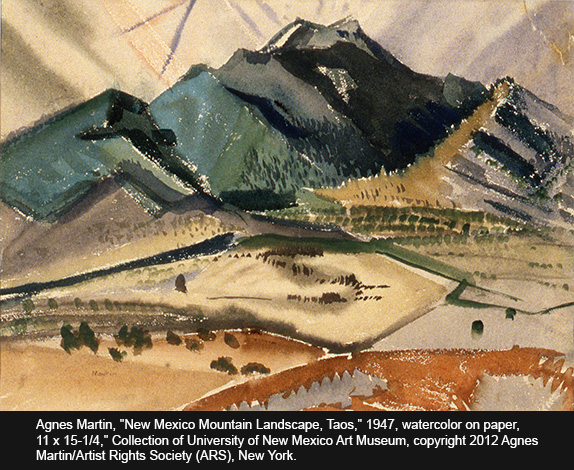

At the University of New Mexico Before the Grid feels like a homecoming. Martin had received her bachelor’s degree at New York’s Columbia University in 1942. But in 1946, she came west and enrolled in the graduate art program at UNM. She was 34 years old, and one of 1100 students in UNM’s College of Fine Arts, whose numbers had swollen from a mere 840 in 1940, due to the G.I. Bill. The following summer she had her first experience of Taos when she joined the UNM Art Department’s summer field course there. And in the fall of 1947, as part of the Art Department’s effort to deal with the burgeoning number of students, she was hired as an adjunct instructor, teaching portrait and still-life painting. Eventually, however, she quit the university job (the pay was too bad) and began teaching art in the Albuquerque Public Schools. It would be interesting to know if there might be anyone still living in the Albuquerque community who would remember having Martin as a teacher.

Sometime around 1950, she built a house on Avalon, a spur that begins at 52nd Street and runs parallel to Central Avenue as it climbs up the West Mesa after crossing the Rio Grande near Old Town. Built with her own hands, the house commanded a view of the river valley below. In January 1950, Richard Diebenkorn came to study at the university on the G.I. Bill and rented a caretaker’s house on a small ranch on Gabaldon Road, near the river, just west of Old Town. The two artists would have been living almost within sight of one another, on opposite sides of the river. Yet there is no indication that they ever had any contact. Although much younger, Diebenkorn was a far more advanced artist than Martin at that time. And while Diebenkorn remained in Albuquerque through the summer of 1952, Martin returned to New York in the fall of 1951. She had gone into debt to build her house. But when she sold it into Albuquerque’s booming real estate market in 1951, she made enough money to finance another year at Columbia, earning her master’s there in June 1952.

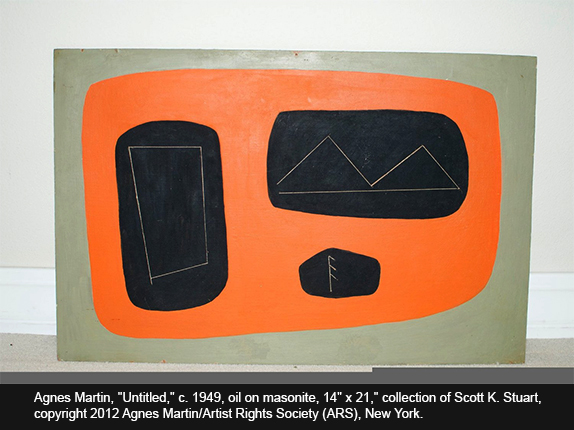

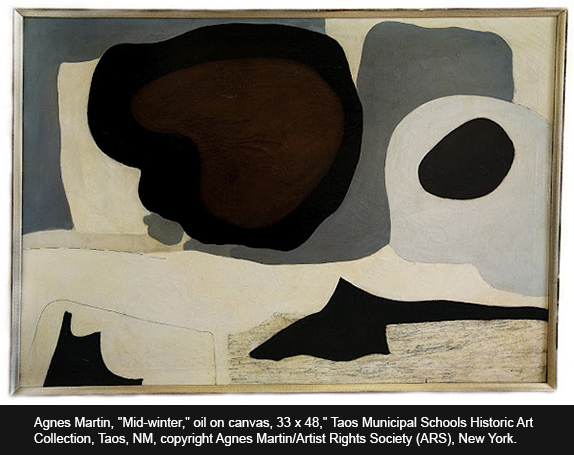

Martin was born the same year as Jackson Pollock, but she came to art late in life, stumbling on it in museums while studying to be a teacher at Columbia University in 1942. She was 30 years old when she decided to be an artist. She would be 50 before she finally worked her way to the delicate tracings of her grid format in 1962. After her breakthrough, however, she seemed to regard her early work like a repentant sinner. She tried to get rid of it, famously destroying everything she could.

Yet Martin was not alone in her impulse to blot out her past. One by one, nearly all of the leading American painters of the mid-twentieth century experienced a decisive break in their work. As Harold Rosenberg noted in his 1952 essay, The American Action Painters, “With a few important exceptions, most of the artists of this vanguard found their way to their present work by being cut in two.” They had discovered a completely new approach to painting, an absolute break with the past that rendered their previous work irrelevant. “It is strange,” Rosenberg commented, “how many segregated individuals came to a dead stop within the past ten years and abandoned, even physically destroyed, the work they had been doing.”

Although she was in New York from 1941 to 1946, Martin seems to have been completely unaware of the avant-garde that was forming around the artist-refugees from the war in Europe, whose interest in the Surrealist technique of automatism would eventually give birth to Abstract Expressionism. Judging from the evidence of Before the Grid (and despite considerable confusion about the dating of works), it was only during her return to Columbia in 1951-52 that Martin first encountered the new Surrealist-based improvisation. She would spend the next few years back in Taos working hard to catch up.

An additional semester at Columbia in 1954 put her in contact with Betty Parsons and the artists of her renowned gallery. Returning to Taos in late 1954, Martin got a grant from the Wurlitzer Foundation using Parsons as a reference. She could then fully concentrate on her work and claimed to have painted 100 paintings during 1955. In late 1957, she returned to New York under Parsons’ wing and got a studio loft in the artists’ enclave at Coenties Slip. There she found support on her path to the grid, particularly in the holistic panels of Ellsworth Kelly and in the open-work fiber pieces of Lenore Tawney.

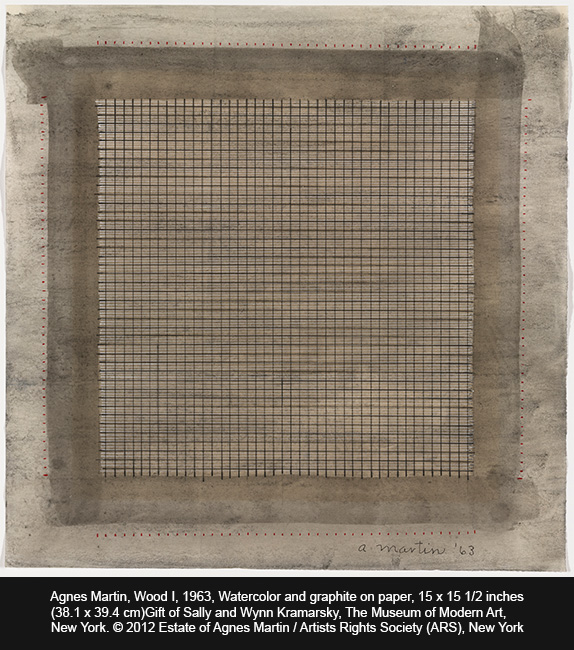

But it was her desire to achieve the presence and profundity of paintings by Rothko, Pollock, and Newman that led to her breakthrough. For that, she needed the example of Ad Reinhardt. She met Reinhardt either at Columbia in 1952 or in Taos that year when he was visiting his friends Ed Corbett and Clay Spohn. It was Reinhardt’s knowledge of Plato and Zen that got her on the right philosophical track. And it was the hauntingly recessive cruciform grid of his paintings—uncompromisingly square paintings with their whispered tonalities sinking toward oneness—that surely inspired Martin’s move to the quiet totality of her grid.

And it was Reinhardt’s sudden death in 1967 that contributed to Martin’s decision to return to New Mexico. That loss coincided with the loss of her lease when her studio loft was slated for destruction, and it led to Martin’s precipitous abandonment of New York at the height of her career. After wandering throughout the West in a camper truck for a year, she eventually settled on rented land on a mesa near Cuba, New Mexico. She stopped painting, however, and the hiatus lasted for seven years. Beginning again only in 1974, she would continue to refine her format for another thirty years, first in Galisteo and then in Taos, until her death in 2004 at age 92.

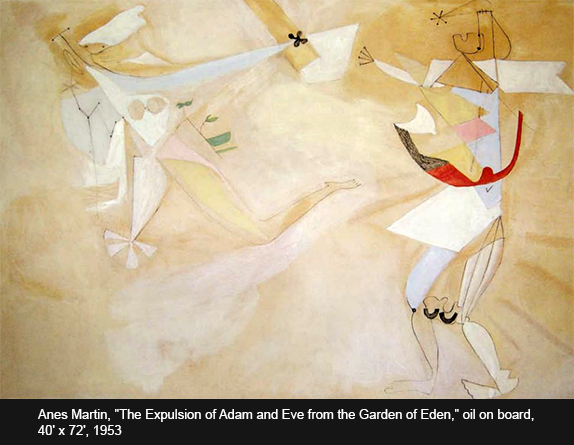

While trying to sort through the many directions of Martin’s early work in Before the Grid, I kept returning to the painting titled The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, 1953. At four by eight feet, it is one of the largest pieces in the show and must have been important for Martin. I was curious to understand what she might have to say about this loaded subject at that point in her career. But the two figures depicted make no sense as Adam and Eve. While the woman is clearly naked as she runs away, the male figure is clothed in a short tunic. And although there are a few leaves, they do not hide her shame, but appear instead to sprout from her side. It soon dawned on me that she is not Eve, but Daphne, and the man with the despairing gesture is not Adam, but Apollo. Martin was illustrating the story of Daphne and Apollo from Classical mythology.

At first, because of Martin’s broad use of biomorphic imagery in the 1950s, I thought the picture might be related to the work of Rothko and Gottlieb in their “mythmaker” phase of the early 1940s. But Martin’s handling of myth has little in common with these artists. Moreover, while she utilizes a kind of shorthand drawing style based on Picasso and Paul Klee, her picture is not really ambiguous. She clearly depicts Daphne’s flight and the beginnings of her metamorphosis as a few leaves of laurel start to sprout from her body. And she shows Apollo’s dismay as Daphne slips from his grasp, punctuating the pivotal turn of fate with a tiny twirling asterisk. Among Martin’s surviving works of this period, no other is so plainly illustrational, and none refers so explicitly to a known narrative from Classical mythology.

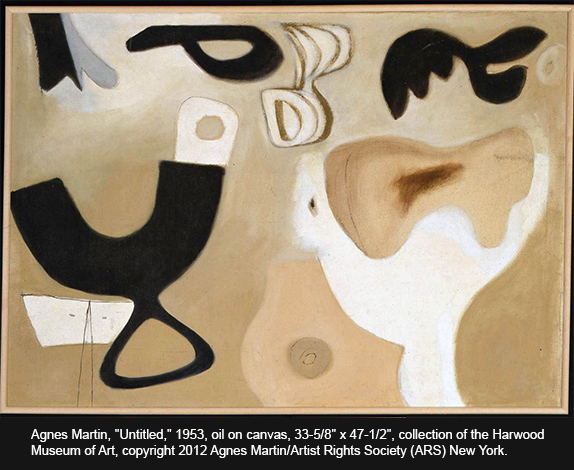

In the show’s catalog, the painting is paired with an untitled biomorphic abstraction in the Harwood’s own collection (p. 49), also dated 1953. That was the first full year that Martin spent in Taos, and while the two pieces differ widely in style, their pairing is suggestive. In certain respects, both seem to have ties to the work of Tom Benrimo, a member of the hip community of “Taos Moderns” in the 1950s that included Bea Mandelman, Louis Ribak, Clay Spohn, Edward Corbett, and Joseph Glasco. The latter two, by the way, had just been exhibited with Pollock and Rothko in 15 Americans at the Museum of Modern Art, which Martin no doubt saw while she was back in New York getting her MFA at Columbia in 1952. Benrimo grew up in New York and brought a sophisticated background in theater design, Surrealism and Bauhaus modernism to Taos. His interest in Greek drama and myths may have nudged Martin’s turn to a mythic subject. And although the biomorphic forms in the Harwood painting mostly defy identification, they find a weird echo in the moonstruck Surrealism of Benrimo’s The Hollow Men, a picture from 1946 that he revised in 1952.

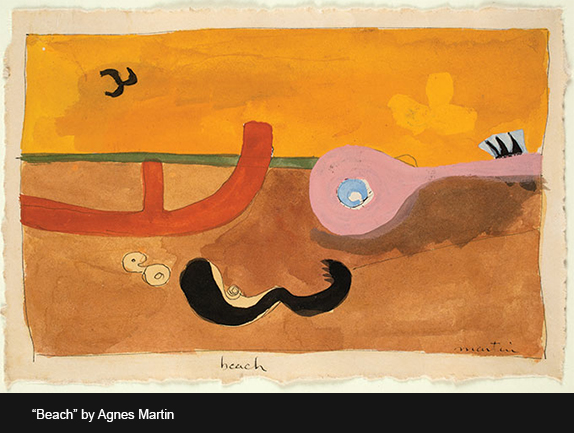

Benrimo could also be a partial source for the Harwood painting’s most startling detail: the emergence of a fleshy image of a woman’s breast. Surrounded by otherwise abstract, enigmatic shapes, the sensuous breast affects how these other forms read. Suddenly they take on suggestions of obstetrics and early post-natal childcare, crib toys and teething rings, and playfully emergent life-forms. There’s a sense of nurture and a sweaty intimacy with the mother’s body, but the mood is apprehensive, alternating between delight and dread. What’s more, the breast has a parallel in a bulbous pink polyp in another of Martin’s biomorphic paintings, titled Beach (p. 38). This undated watercolor features hints of Surrealistic marine life—snail, eel and oyster-like forms aligned on the sand—which, together with the pearl nestled inside the eel/oyster, suggest that both of these biomorphic paintings fantasize on themes of female sexuality.

In the show’s catalog essay, Dr. Richard Tobin has little to say about the Taos Moderns and makes no mention of the painting I questioned. When I pointed out the discrepancy between title and subject in a letter to Santa Fe’s THE Magazine in June 2012, however, Dr. Tobin wrote a response in July. He explained that the title Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden goes back to the painting’s original owner, who is identified as having been a “partner” of Agnes Martin, and hence someone who presumably ought to have known its title or subject.

Dr. Tobin also expressed a desire to stick with the Biblical title, since it lends support to his notions about the impact of Calvinism on Martin’s conscience, a supposed legacy of her Scottish-Presbyterian upbringing in Canada. In Tobin’s view, Martin’s efforts to purify her work are informed by Calvin’s convictions about humanity’s “absolute depravity,” a fall from grace as a result of Original Sin, and the soul’s thorny problem of “predestination.” (Calvin taught that Salvation is not universally granted and that even after repentance you cannot really know if you are among the Elect.)

It’s true that in The Untroubled Mind (the most often-quoted of her published writings) Martin is fond of reciting Isaiah and says things that sound like a response to Calvin’s predestination—“Everyone is chosen and everyone knows it, including plants and animals” and “You can’t get away from what you have to do.” But despite the tenor of her metaphors, her ideas are based in a more general (non-doctrinal) concept of destiny and the possibility of fulfilling one’s potential through inspiration. “Inspiration and life are equivalents,” she said, “and they come from outside.” And she pointed out: “These paintings are about freedom from the cares of the world, from worldliness. Not religion. You don’t have to be religious to have inspirations.”

Although Martin’s picture found its way into the hands of a “partner,” we really know nothing about its actual origins or intended meaning. Without much context to go on, it’s easy to be led astray by preconceptions and by not really looking.

Could it matter, then, that elsewhere in the exhibition (p. 43 of the catalog) we find that Martin made a portrait of someone named Daphne? Who was Daphne Vaughn? Martin painted her sometime between 1947 and 1949 in a style reminiscent of Matisse via Willard Nash, one of Santa Fe’s “Cinco Pintores” (whose WPA mural of collegiate sports graced UNM’s library in those days). Could the 1953 painting be in any way a private allegory about her, a playful improvisation on her name? Might it even be possible, if that were the case, that there could have been something in Agnes’s relationship with this Daphne that she didn’t care to have her “partner” know about, letting her believe instead that the painting is about Adam and Eve? We really don’t know what the human dynamics might have been, and it’s probably none of our business, but the “partner” was either mistaken or misinformed (or hiding something?) about the picture’s subject.

Of course, the failure of any relationship—even one that is only imagined, its love unrequited—can feel like an expulsion from Paradise. So maybe we also need to recognize that, whatever else might be at stake, to make a painting about the story of the mythical Daphne is, on some level at least, to make a work about the avoidance of love.

Although Ovid’s The Metamorphoses was the usual source of myths for artists, Martin more likely turned to Edith Hamilton’s Mythology, which appeared in a popular paperback edition in 1953. In a chapter titled “Eight Brief Tales of Lovers,” where she usually gives both lovers’ names in her headings (Pyramus and Thisbe; Orpheus and Eurydice), Hamilton has a section labeled only “Daphne.” It begins: “Daphne was another of those independent, love-and-marriage hating young huntresses who are met with so often in mythological stories.”

Focusing entirely on Daphne’s plight as an “unfortunate maiden” who wants freedom but finds herself lusted after by a god, Hamilton leaves out the whole back story about Apollo and his argument with Cupid over their respective archery skills. (In spiteful retaliation, Cupid shoots an arrow with a gold tip into Apollo’s heart, enflaming his desire, while he strikes Daphne with one tipped in lead, deadening hers.) Who can say why Martin chose to make an image of Daphne’s hurtling flight? And why would she show the love-struck Apollo stopped in his tracks, pantomiming loss? Would she identify with the bereft Apollo, whose object of desire, muse, and inspiration has just fled? Or does she identify with the sexually panicked and freedom-loving Daphne?

To save her from the god’s love, Daphne is transformed into a tree. “When I first made a grid I happened to be thinking of the innocence of trees,” Martin said in a 1989 interview with Suzanne Campbell, “and then this grid came into my mind and I thought it represented innocence, and I still do, and so I painted it and then I was satisfied. I thought, this is my vision.”

Innocence? Of trees? Innocence was a key word in Martin’s vocabulary, along with “happiness” and “inspiration.” For her, innocence and happiness are primal states, equivalent to what used to be meant by “bliss” (of a heavenly sort). “In Genesis Eve ate the apple of knowledge of good and evil. When you give up the idea of right and wrong you don’t get anything. What you do is get rid of everything,” Martin said in The Untroubled Mind. (This, as near as I can tell, is Martin’s only recorded reference to the Adam and Eve story.)

Innocence, for Martin, is linked to inspiration. “To live and work by inspiration you have to stop thinking,” she wrote in The Current of the River of Life Moves Us (a talk she gave at UNM in 1979 and later revised for publication in Artspace, Nov./Dec. 1989). “You have to hold your mind still in order to hear inspiration clearly.”

In The Untroubled Mind she went further, explaining that the process of emptying the mind leads to dissolving the ego. Through her Zen studies she recognized that ego and pride will, in any case, ultimately be subsumed in the way of the world: “By bringing thoughts to the surface of my mind I can watch them dissolve,” she wrote, “I can see my ego and see its intentions. I can see that it is the same as all nature. I can see that it is myself and impotent like all nature, impotent in the process of dissolution of ego, of itself. …The dissolution of ego in reality as it was in the beginning, as it was before we were separate and insular, the process we call destiny, in which we are the material to be dissolved.”

If nothing else, the works gathered in Before the Grid show Martin chasing inspiration. Trying to find a spiritual vocabulary expressive of innocent beginnings and a kind of universal genesis, she took up the tools and modes available to her at the time. “I made paintings for twenty years without liking them,” she told Joan Simon (Art in America, July 1996), “because I wanted something else. What I wanted was to get more abstract. When I got to the grids, and they were completely abstract, then I was satisfied.”

Her discovery of the grid format was a breakthrough into a new form of painting, in line with that of the other major artists of mid-century America: Pollock, Still, Rothko, Newman, Reinhardt. “I consider myself one of them,” she said to Benita Eisler (in The New Yorker, January 25, 1993), referring to the Abstract Expressionists. “They had a whole philosophy. They gave up positive and negative space, and, as a result, they got tremendous scale in their work. And they didn’t do it gradually. They moved in one step to complete non objectivity.”

It was a breakthrough into a form of holistic painting that was unlike anything seen before in the history of art. While this “all-over,” holistic painting was unprecedented in many ways, one of its least understood aspects was that it put a completely new slant on the old idea of “representation.”

Martin’s friend and mentor, Ad Reinhardt, drew a cartoon about this idea. It shows an abstract, Mondrian-like grid painting hanging on the wall with a behatted bourgeois middlebrow in a business suit pointing at it derisively. “Ha Ha,” laughs the middlebrow, “What does this represent?” In the next frame, the painting points back at the middlebrow, sternly demanding: “What do you represent?” The new painting questions everything the bourgeois middlebrow stands for—everything he represents.

What the new holistic painting showed was that earlier painting had often been a confused blending of impulses—the making of representations of the world, as it is seen; and making representations to the world, as in a court of law. The first was mainly concerned with rendering the appearances of things encountered in the world, a form of commemoration. The second was essentially about self-expression (often on behalf of the community), and a matter of making appeals or protests, or of offering homage and praise, to the world at large.

But the new painting would no longer be about mediation. Instead, it proposed a condition of absolute immediacy. Nothing would come between the painting and the beholder. There would be no reference to anything extraneous, no depiction of anything not present, no allusion to any other time but the present moment.

“What you do is get rid of everything.” Martin’s grid emptied her painting out and returned it to a state of innocence.

Responses to “Some Late Thoughts on the Early Work of Agnes Martin”