With Visualizing Albuquerque having run its course at the Albuquerque Museum, and with a new documentary on “Painting Albuquerque” soon to be broadcast on KNME-TV, it’s possible to take stock of the unique character of Albuquerque’s art scene as it evolved after 1950.

Albuquerque’s urban edge sets its art apart from the earlier art colonies of Taos and Santa Fe, which were bound up with nostalgia for village life and the romance of New Mexico’s landscape and ethnic cultural traditions, in particular, the enduring nature of Pueblo spirituality. After 1945, the Cold War defense industry boosted Albuquerque’s economy and the city’s burgeoning population bolstered its metropolitan ambitions. The University became an increasingly important factor in shaping the local art scene, and in the 1960s it gave its full support to a new spirit of modernism.

Modernism represents a self-conscious quest for honesty in art. Born of the Enlightenment’s belief in the rational perfectibility of human life and its questioning of all traditional forms of authority, modernism involves a critical self-examination of art’s nature and purpose. It seeks to justify art’s continued existence in the face of changes wrought by industrialization, by the expansion of scientific knowledge, and by the increasing progress of global communications that developed during the nineteenth century. The new medium of photography with its mechanical rendering of visual data, together with exposure brought by colonialism and world trade to such alien art forms as those of Japan and Africa, led to a new consciousness of the relativity of image making. The longstanding European tradition of rendering appearances in art came up for critical reappraisal. Artists felt the need to be interpreters of their own times, hence the term “modern.” But they became aware that their active role as interpreters shaped the actual images they made. So, in all honesty, they made that individual shaping an aspect of concern, introducing it into the images they produced.

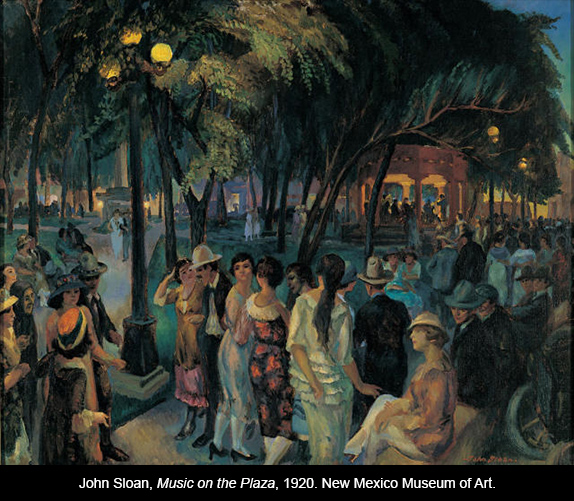

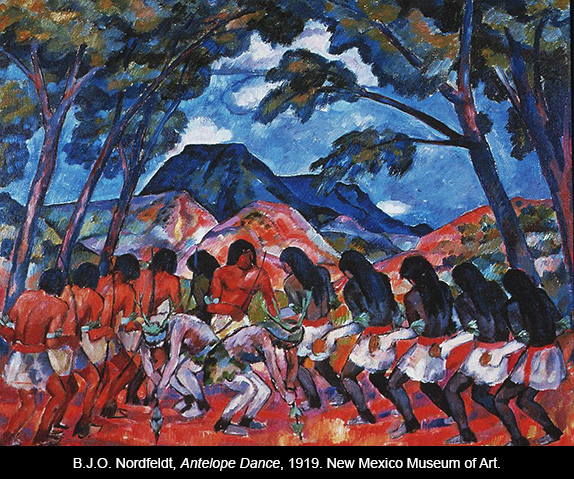

The form of modernism that came to Albuquerque in the 1950s differed significantly from the earlier waves of modernism that came to New Mexico with the so-called “Ash Can” artists and with the artists from the New York circle of Alfred Stieglitz and Mabel Dodge. Modernism for the Ash Can artists, Robert Henri and John Sloan, who arrived in Santa Fe in 1917, was essentially tied to what they considered to be a new attitude toward subject matter. Like Courbet in the mid-nineteenth century, they were in revolt against the perceived falsity of prevailing “bourgeois” values and the rigid strictures of academic art training, including the whole stogy rationale of its “morally uplifting” Neo-Classicism (which we had a rare chance to examine last fall in the Albuquerque Museum’s Gods and Heroes exhibit). Against the academy, the Ash Can artists proposed a more liberated approach to technique; and against the vacuous refinements of the bourgeoisie, they sought a subject matter beyond the margins of “polite” society—associated with the “trashcans” of the streets and among the lower ranks of “the people,” whom they felt led a more “authentic” existence. In Santa Fe these “marginal” and “authentic” people were found among the Native Americans and Hispanic farmers and the hoi polloi on the plaza. Both the Native and Hispanic inhabitants were admired for holding onto age-old traditions that had endured through time, in stark contrast to the runaway mechanization, exploitation, and perceived decadence of modern urban society.

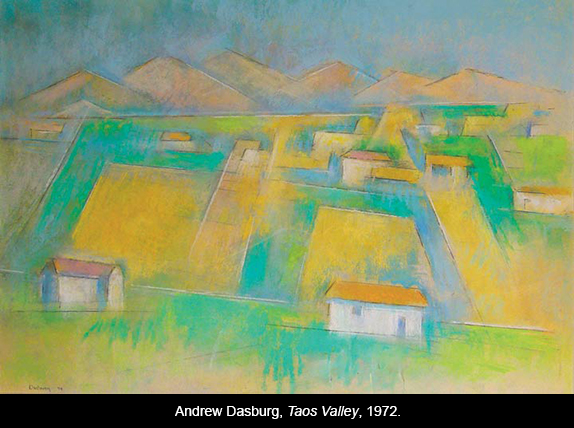

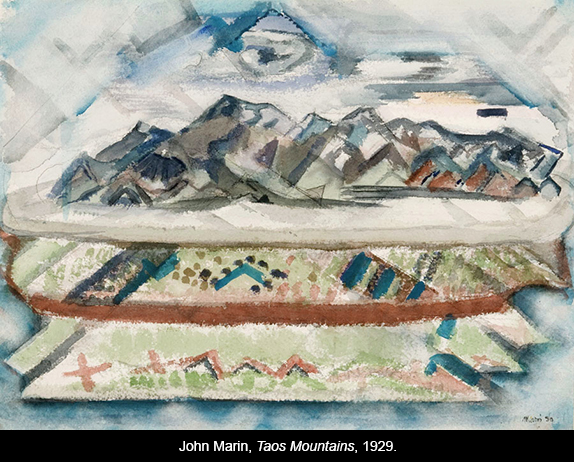

All of the other early modernists—whether in the Stieglitz/Mable Dodge circle (Dasburg, Hartley, Marin, O’Keeffe) or from Chicago (Nordfeldt, Jonson, Henderson, Baumann, Higgins) or members of the Cinco Pintores or even later arrivals like Ward Lockwood and Cady Wells—essentially applied a modernist formal vocabulary to the depiction of regional subject matter. Dasburg, Nordfeldt, and Marin, for example, would simply utilize the shifting planes and geometric outlines of Cezanne and the Cubists when describing a landscape or Pueblo dance group. Georgia O’Keeffe would find the elemental forms of Brancusi in the desert’s sun-bleached bones and in the eroded contours of mesas.

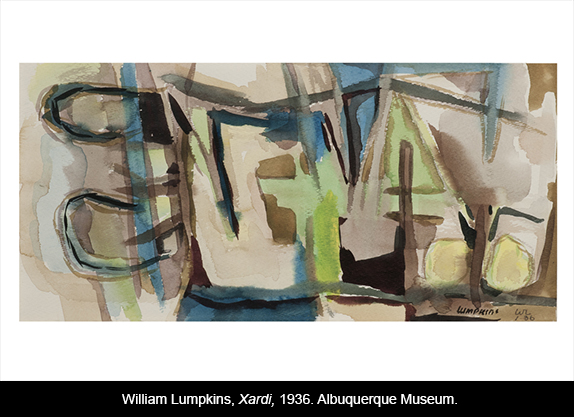

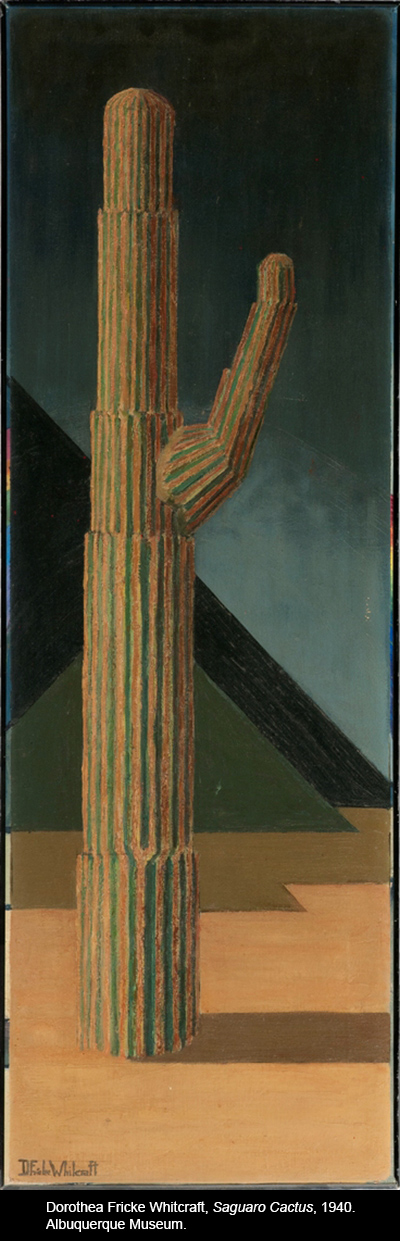

O’Keeffe first came to New Mexico to make art in 1929. She came at the invitation of Mable Dodge, who also invited John Marin and had earlier brought D. H. Lawrence to Taos. That same year, Dorothea Fricke Whitcraft was instrumental in founding the art department at the University of New Mexico, where she taught life drawing. One of her students in 1929 was William Lumpkins. Another teacher at UNM at the time, Loren Mozley, introduced Lumpkins to the watercolors that John Marin painted in New Mexico in 1929-30, which placed Lumpkins on his own modernist track and would eventually lead to his joining Raymond Jonson’s Transcendental Painting Group in 1938. The nearest reflection of Cubist influence among the early modernist artworks in Visualizing Albuquerque appears in Whitcraft’s Saguaro Cactus, 1940, with its segmented plant and abstract geometric background. Mysteriously, Whitcraft’s Saguaro didn’t make it into the show, although it is reproduced in the catalog. There, unfortunately, it is badly cropped, leaving out its most significant modernist feature—a thin border of subtly painted, prismatic colors. Inspired by the “fake” frames painted into both “Analytic” and “Orphic” Cubist paintings, the border sets off the painting as an independent, self-contained object. As can be seen here, with the border restored, the surrounding shimmer of light becomes like the edge of a beveled mirror. Rather than holding a mirror up to nature, however, the picture declares itself as a sophisticated handmade artifice.

Forty years later, after the mid-century arrival of a wholly new form of modernism in New Mexico, a similar declaration of artifice can be found in A Hidden Desire, 1984, by Elen Feinberg. A much later but equally accomplished art professor at UNM (who occasionally taught life drawing as well), Feinberg also employs geometric elements within what appears to be a still-life set up. But geometry, which is associated with the rational, is here subverted by the irrational. Despite delicate modeling of light and color, unexplainable discrepancies occur among cast shadows and, especially, the two table legs on the right, so the apparent rendering of reality is exposed as unreal—an invented abstraction.

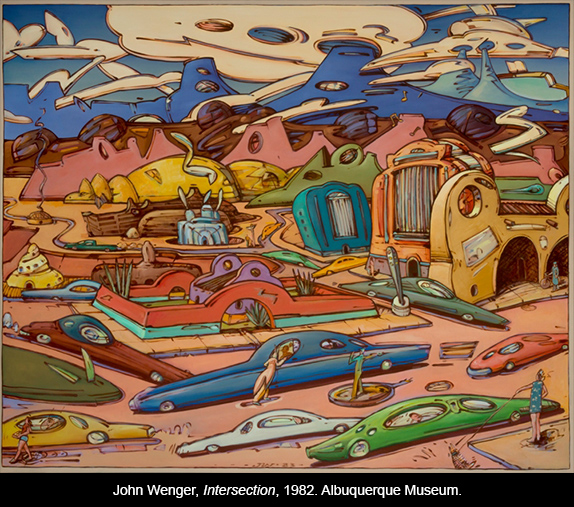

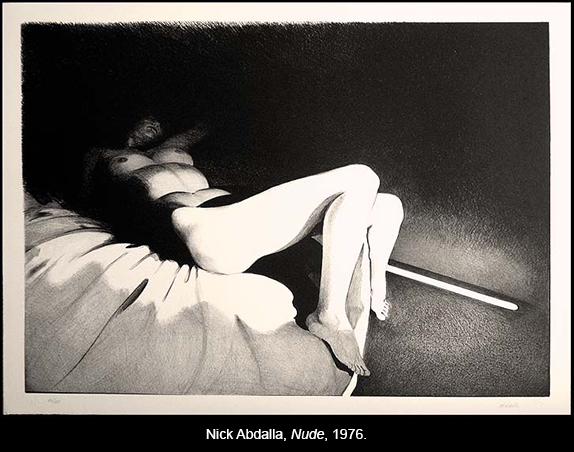

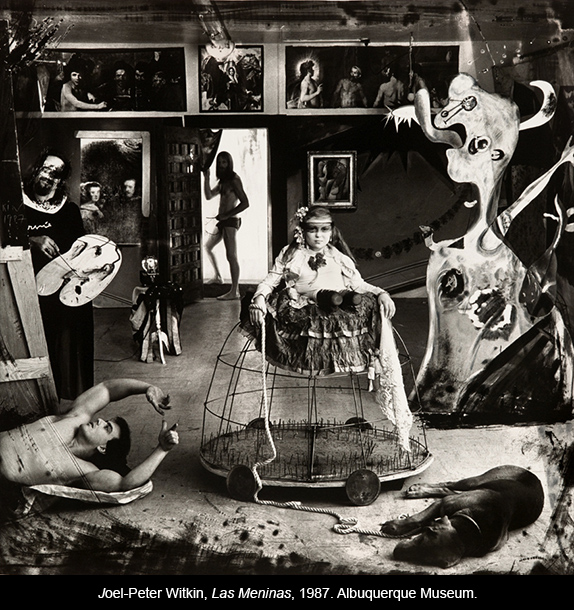

This stress on artificiality and questioning the traditional conventions of picturing continued to define the modernist attitude toward representational images, especially after the late 1950s when the so-called Pop artists discovered the power of imagery borrowed from the popular mass-media. When dealing with representation, modernism forthrightly shows its hand as stylized image-making, as can be seen in the hallucinatory imagery of Bruce Lowney and John Wenger, which relies on a whimsical animation of cartoon-like exaggerations. Images are often unmistakably second-hand, as in Carl Johansen’s ironic appropriations of Picasso and Dürer mixed with cowboy kitsch. And if the artifice of photography is referenced in Nick Abdalla’s hand-drawn nude, Joel-Peter Witkin’s photographic enterprise is entirely built on the subversion (perversion?) of photography’s truth-telling pretensions.

But mid-century modernism is more distinctly identified with a form of painterly abstraction that is almost entirely non-representational.

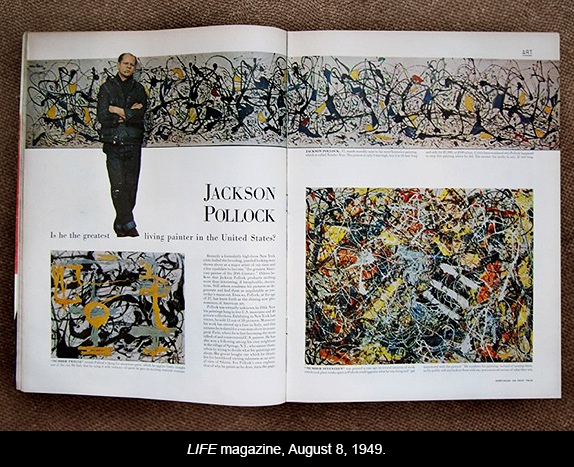

The first inklings of this new direction likely came to Albuquerque via the media. In its August 8, 1949 issue, Life magazine asked: “Jackson Pollock: is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” Whether or not Albuquerque’s mid-century artists could afford a subscription to Life, they would certainly have been aware of how that question was rocking the art world. Pollock became the poster child for a sea change in the art of painting.

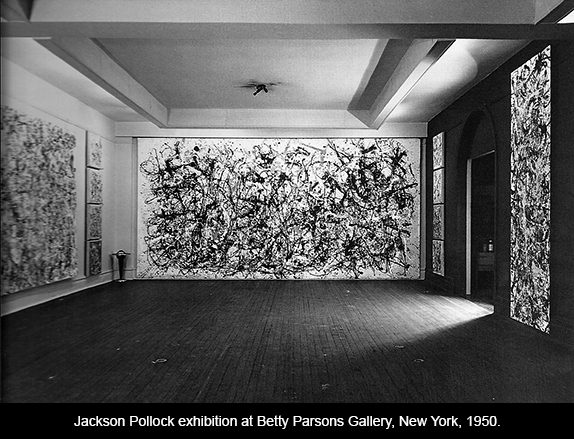

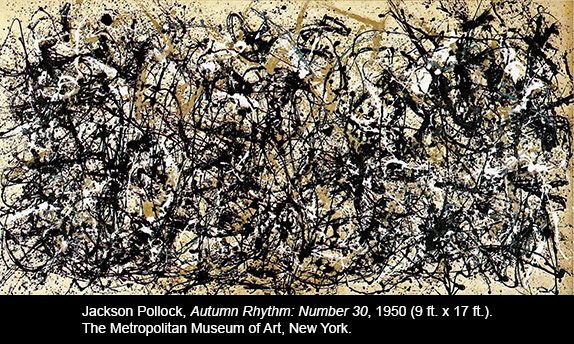

If we look at this photo of Pollock’s 1950 show at the Betty Parsons Gallery, I think we can get the full impact of what makes his work so revolutionary. One thing that’s clear: he was no longer making easel paintings. Just the size of the paintings is arresting—and confrontational. They not only fill the space in front of you, but you simply cannot avoid the fact that these are quite frankly paintings, not pictures. No longer pretending to represent anything not present, they are paintings made of paint and what paint does as physical matter. Liquid paint is skillfully manipulated in rhythmic flows and spatters in layered tracery patterns that expand evenly over the entire canvas surface, giving the eye no rest—the now famous “all-over” effect. Moreover, the paintings keep the process of their making right there before your eyes. If they form a picture of anything, it’s of a sort of universal genesis—the ongoing process of creation, held forever in the suspense of its unfolding. There’s a startlingly direct honesty in this literalness; the paintings are not trying to be anything other than what they are.

Yet they are expressive, and also tremendously self-contained with what seems to be a kind of autonomous life of their own. Spreading out before you, they are like standing in front of some overpowering natural phenomenon—a welling storm, or Niagara Falls, or perhaps the awesome infinity of the churning cosmos itself.

Everyone knows the famous anecdote told by Pollock’s wife, Lee Krasner: “I brought [Hans] Hofmann up to meet Pollock for the first time and Hofmann said, after looking at his work, ‘You do not work from Nature.’ Pollock’s answer was, ‘I am nature.’” Pollock’s one-liner is so good that what Krasner says next is usually overlooked: “I think this statement articulates an important difference between French painting and what followed. It breaks once and for all with the concept that was still more or less present in Cubist derived painting, that one sits and observes nature that is out there. Rather, it claims a oneness.”

Pollock used the term “French painting” for the whole of the modernist tradition up to his time—Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Matisse and Picasso. “Oneness,” however, was a supremely important concept for him, reflected in his fondness for titling his work “One” (as in One, Number 1A, 1948 at MoMA). It came from a deep need to express an underlying unity of being. Jeffrey Potter, in his contribution to Such Desperate Joy (pp. 88–89), quotes Pollock on “Oneness” (which Potter labels “God”): “Why give Him—faith—a name?” says Pollock, “Like titling a work—isn’t ‘One,’ or ‘The One,’ enough? Way I see it, we’re all part of the one, making it whole. That’s enough, being part of something bigger. Let the Salvation Army take over the gods. We’re part of the great all, in our lives and work. Union, that’s us.” Later Pollock adds: “An artist knows what he’s doing, or should. It’s not something you talk about, only feel—deep, deep inside. What I do, I unite parts of union into a bigger whole. With enough, that created whole turns into being.”

This was a heavy program for art; but similarly charged statements about the ambitions of abstraction were also being made by Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman. What came to be called Abstract Expressionism was an attempt to create a holistic art with a spiritual resonance.

Representational art had always referred to a reality—a figure, a landscape, a vase of flowers—which was not present, but simply re-presented in line and color. But in the holistic approach of the new abstraction, there would be no reference to anything extraneous, no depiction of anything not present, no allusion to any other time but the present moment. The new painting would no longer be about mediation. Instead, it proposed a condition of absolute immediacy. Nothing would come between the painting and the beholder.

Richard Diebenkorn was probably the earliest artist to arrive in Albuquerque with advanced first-hand knowledge of the improvisational basis of the new abstraction. Desiring to take advantage of the G.I. Bill to further his development, he came to UNM as a graduate student in 1950, having already studied and taught at San Francisco’s leading art school with such figures as Clyfford Still and Mark Rothko. Diebenkorn’s approach was like that of a jazz musician, spontaneously improvised in sudden spurts and long lyric lines resonant with emotion. His hand operated like a seismograph, tracking his shifting consciousness and allowing traces of his experience of the environment to enter in—the light and color and broad space of the high desert and hints of animal or land forms. He became an important influence on his fellow students and the younger faculty members, Herb Goldberg, William Howard, and Enrique Montenegro.

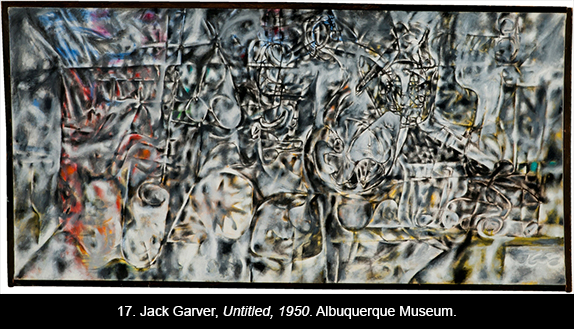

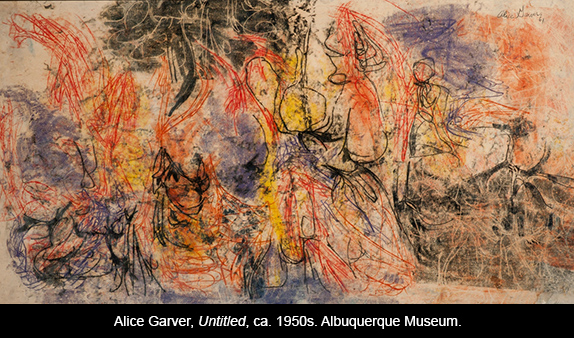

It was in the work of Alice and Jack Garver, however, that the impact of Pollock’s “all-over” linear effect can best be seen. In addition to the densely intricate complexity of looping lines in their paintings, there’s an autonomous quality, as if the painting had somehow, at least in part, materialized by itself, freed from the artist’s hand. In Jack’s painting this is achieved by the misting of aerosol paint. In Alice’s it’s the product of an off-setting technique in which color is transferred from another surface by rubbing, so that it doesn’t seem to have been painted, but appears to be a natural discoloration.

Because of increased mobility (air travel, the new interstate highway system) and the influx of other artists via the University who were fully in touch with the new sensibility, and because of the wide circulation of magazines such as Art News and Art Digest, artists in Albuquerque in the 1950s did not necessarily feel cut off from the mainstream. Instead, they felt they were a part of a wide-open and widespread movement that could be seen manifesting itself on both coasts (New York and San Francisco simultaneously), in Europe and South America—and even in Taos! That a group of hip and like-minded artists was emerging in Taos and in Albuquerque at the same moment allowed for vital exchange between the two art communities. Some of Albuquerque’s modernists showed at the Galeria Escondida in Taos; and Jonson presented the first definitive show of “the Taos Moderns” at his Albuquerque gallery in 1956.

In Albuquerque, the chief problem was that of support and acceptance from the wider community. No one really expected to be able to make a living at their art in those days (not even in New York!). But to have a receptive audience eventually mattered. There was no museum for showing art in Albuquerque, however, and Jonson’s gallery began as practically the only showcase. Jonson retired from teaching at UNM in 1954, but he maintained his program of exhibitions at his gallery and continued his evangelism on behalf of abstract art. Beyond the Jonson, other artist-initiated efforts soon sprang up, including the Vincent Garrofolo Gallery in Old Town, a co-op called The Barn, Bob and Peg Hooton’s Workshop Originals, and Bob LaPlante’s small showplace in his frame shop.

In 1950, Adja Yunkers formed the Rio Grande Graphics Workshop, producing a modernist portfolio, Prints in the Desert, with the intent that the prints would be priced accessibly as “a means of placing the highest art in the most hands.” Participants included Frederick O’Hara, Robert Walters, and Jack Garver. Born in Latvia, and having lived all over Europe and the Americas before coming to New Mexico on a Guggenheim grant and as a visiting faculty member at UNM, Yunkers personified the new international modernism as fully as anyone. His ambition was to start up an independent art school in Albuquerque, along the lines of Black Mountain College. Richard Diebenkorn and many other younger artists had hoped to find employment there, before the whole thing ran aground on the issue of support, devolving into a nasty lawsuit.

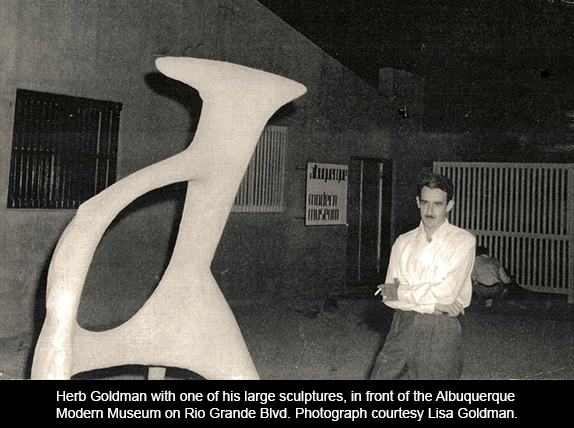

In 1953, a rather heroic group of artists banded together in a grass-roots volunteer effort to form an Albuquerque Modern Museum, which opened in a communally refurbished bean warehouse at 3800 Rio Grande Boulevard NW between Candelaria and Griegos. It lasted until 1956 and presented an ambitious program of exhibitions and outreach including studio art classes in a variety of disciplines as well as classes and public performances of modern dance. The Modern Museum was the brain-child of painters Robert Walters and William Vaughn Howard, with the participation of Frederick O’Hara, Carl Coker, and sculptor Herb Goldman. Elizabeth Waters spearheaded dance, and Walter Keller of the UNM music faculty programmed musical evenings. Artists who exhibited at the Modern Museum included: Rita Deanin Abbey, Kenneth Adams, Malcolm Brown, Douglas Denniston, Richard Diebenkorn, Ralph Douglass, Alice and Jack Garver, Lez Haas, Raymond Jonson, Alexander Masley, Enrique Montenegro, Rose Mary Mack, Joan Oppenheimer, Horace and Florence Pierce, Howard Schleeter, John Tatschl, and Adja Yunkers.

In 1958, Elaine de Kooning, wife of the influential New York Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning, came to UNM as a visiting professor in the art department. She was impressed with the vigor of the local art scene and actively advocated for its wider recognition. She curated a show of Albuquerque artists at the Great Jones Gallery in New York in 1960, and saw to it that it was reviewed in Art News. She even wrote a piece for Art in America, published in 1961, in which she remarked that New Mexico has “a landscape so overwhelming that painters have to look inside. Here is a strongly introspective art, stubbornly original and personal, yet not eccentric.” Artists selected for her New York show were: Jean Armstead, Albert Barela, William Conger, Connie Fox, Alice Garver, Lez Haas, William Vaughn Howard, Don Ivers, Raymond Jonson, Richard Kurman, Ralph Lewis, Joan Oppenheimer, Enza Quargnali, and Robert Walters.

“Albuquerque, impersonal and uningratiating as a gasoline station, nestles in the Rockies under a sun forty percent brighter than New York’s,” wrote de Kooning in her introductory essay for the exhibition. “Light resounds and reverberates over the city, drastically magnifies and diminishes the buildings, brings the surfaces of the mountains aggressively close or thrusts them off to legendary distances.”

“This opulent landscape,” she continued, “has spawned hundreds of buckeye painters who try to pin it down and succeed only in reducing the grand to the picturesque.” By contrast, she noted, “It might be said that the sun chased the modern artists indoors. The most inspired artists often seem to respond to their surroundings in reverse. Drenched in color, the Albuquerque painters generally work with palettes that are subdued, dense, introverted. Space-rich, they do not need to escape into big canvases as New Yorkers seem to and their forms are compressed and immediate.”

She points out that, “The University of New Mexico is the cultural focus of the city,” and goes on to characterize the situation in relation to New York: “The artists in Albuquerque relate to New York artists today the way New Yorkers related to Parisians in the thirties… Like New Yorkers most of them were born elsewhere and have a fierce, defensive devotion to the city of their choice. Also reminiscent of the New York art world of the thirties is the depression atmosphere—the impossibility of living by painting and the resulting bitterness and acrid humor. The outsize canvas might be uncommon in Albuquerque—as it was in New York not so long ago—simply because most artists can’t afford them. There are several gloomy advantages, however, to being neglected—the main one being that a glorious, tough originality blooms in isolation and tends to vanish in an atmosphere of easy acceptance.” And she credited Raymond Jonson as “probably the factor most responsible for encouraging the intense productivity and high level of professionalism of the young Albuquerque artists.”

The drive toward a reconfigured “professionalism” in UNM’s art department gained momentum in the 1960s under Clinton Adams and Van Deren Coke. The upside was an even greater sense of integration into the international art environment. This was accomplished through increased emphasis on bringing out artists and art historians with international reputations as both visiting and permanent faculty. Another factor was the 1970 relocation of the Tamarind Lithography Workshop to the UNM campus as Tamarind Institute with its significant roster of invited guest artists from all over the world. And finally there was the establishment, under Coke, of the University Art Museum, the first true museum of art in the city. At the University Art Museum, Coke not only mounted as its inaugural exhibition in 1963 the first coherent survey of the history of New Mexico art, but he also began building a distinguished collection and bringing in traveling shows of international interest, exposing students and the local art community to art trends and expressions on a first-hand basis that would otherwise have been unavailable here.

But there was also a downside to this drive toward “professionalism” in art—and it was not restricted to UNM but endemic to universities throughout the nation. Under pressure to justify themselves within the academic degree-granting system of their universities, art departments had to face the fact that creative work cannot be defined as an academic discipline. Emphasis had to be placed instead on art history and theory—eventually privileging theory over practice. Instead of training professional artists, they were increasingly training future professors of art. As candidates for a Master of Fine Arts degree, student artists were expected to defend their presented body of work with a full theoretical rationalization. It was the beginning of a reformulated institutionalization of art that has proved to be as stultifying in its own way as the neo-classical art academies of the nineteenth century.

On the positive side, however, it meant that the best of UNM’s faculty and students took art seriously. Those who were willing to make the commitment felt that they were painting for the museums—that their work should be good enough to bear comparison with the art already acknowledged and hanging on the walls of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It’s a competitive element that has driven artistic accomplishment throughout the ages. Coming onto the city’s art scene in the mid 1970s, I felt this level of ambition was present to an extraordinary degree among Albuquerque’s artists; and it was for that reason alone that the idea of producing an art magazine here had even seemed feasible.

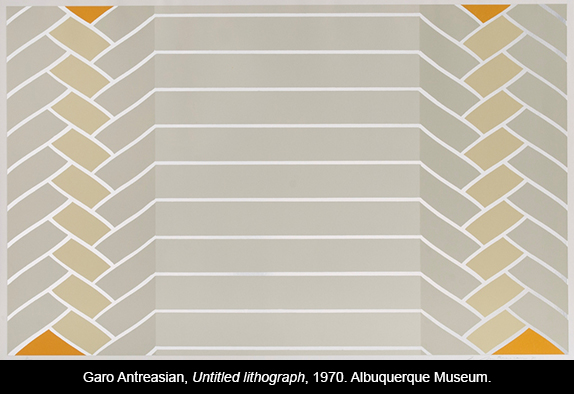

It was in the phase of high modernism promoted by the University during the 1960s, 70s, and 80s that Albuquerque painting realized some of its finest achievements, beginning with the pure, hard-edged, geometric abstraction of Clinton Adams, Garo Antreasian, and Frederick Hammersley. Turning away from the old method of composition based on a hierarchical ordering of uneven parts, Hammersley simply divided his square painting into a grid of nine equal squares. There’s an equality of elements within the uniform block of Hammersley’s square grid, which gives his paintings a firm feeling of self-sustained integrity and independence.

The grid has been used by artists as far back as the Egyptians to organize the space of their pictures. But in the twentieth century it took on new meaning as abstract artists, such as Mondrian, collapsed the space of painting in their search for an impersonal, objective structure that they believed to be universal. In the 1960s, Agnes Martin discovered that the grid produced an impersonal, universalizing effect similar to Pollock’s “all-over” drips, creating an autonomous unity that resulted in a self-contained, holistic painting.

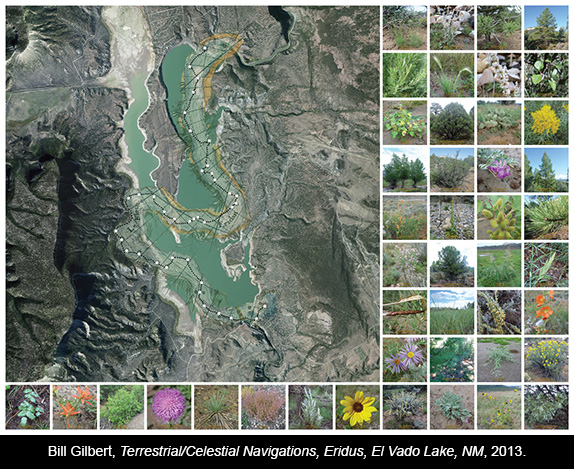

This was an unexpected mutation of Pollock’s messy “all-over” approach and it led to what came to be called a “systemic” form of abstraction. The artist devised a “system” of predetermined moves, which, once in place, would be followed in laying out and executing the artwork. The idea was to have a kind of automatic procedure that would free the artwork from the artist’s hands, making it essentially integral and autonomous. Often this resulted in an objective pattern of repeated forms, and was especially prevalent in the Minimalist art of the 1960s and 70s. Artists who have employed a systemic approach to abstraction would include not only Hammersley and Antreasian, but also Harry Nadler and Aaron Karp. Eventually, the systemic approach mutated into “Process art,” which called for certain specified actions or procedures to be followed, which would effectively produce the art more or less automatically and yet bring about a heightened awareness of the multiple factors at play in any given situation, as seen in Bill Gilbert’s Terrestrial/Celestial Navigations, 2013.

Aaron Karp and Jane Abrams achieve Pollock’s “all-over” effect in dramatically different ways. Karp uses a strategy of systemic abstraction involving multiple layers of jewel-like pigment applied through a variety of taped patterns that are placed, painted, and then removed and re-taped. Abrams employs a representational strategy, filling the surface uniformly with a dazzling variety of colors and marks in a tapestry-like depiction of foliage and the shimmer of reflections on water.

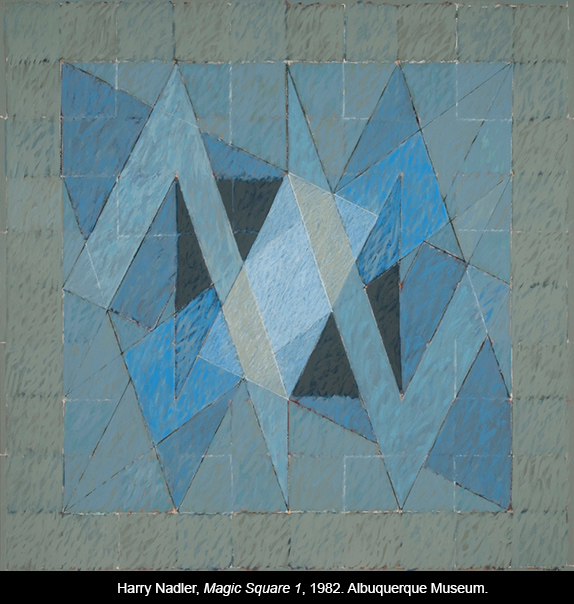

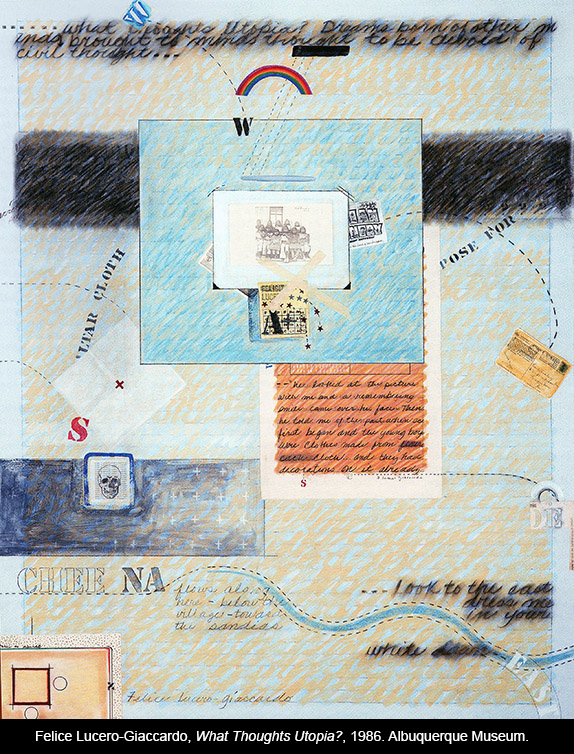

Another interesting comparison might be made between Harry Nadler’s Magic Square 1, 1982, and Felice Lucero-Giaccardo’s What Thoughts Utopia?, 1986. Nadler was Lucero-Giaccardo’s teacher at UNM, and in these examples both artists modify a systemic grid with uniform linear brushstrokes and use it to organize an exploration of their ethnic roots. Nadler discovered that among his ancestors were Sephardic Jews in Moorish Spain, and he utilizes the arcane mathematics of the magic square to invoke the hidden mysteries of the Kabala and to suggest the tile work and manuscripts of a people leading a closeted existence and forced to maintain themselves in secret. For Lucero-Giaccardo the grid becomes like the lined page of a school notebook and helps her to map both the territory and her memories of life at San Felipe pueblo. Bits of stenciled lettering, passages of longhand writing, scattered tourist postcards and collage elements punctuate the grid. A photograph of her grandfather’s grade school class is captioned with a text about his wearing clothes made of flour sack cloth, while beside it a reference to a church altar cloth is marked with a red plus sign and tiny plus signs are gathered below in a dark patch mapping a church graveyard. Poignant phrases appear here and there. Writing that straddles the mapped river in the lower right reads: …look to the east…dress me in your white dawn.

In whatever form it might take, modernism insisted that what matters in art is integrity. Does the work hold together? Is it internally consistent in its form and execution and coherent in its ideas?

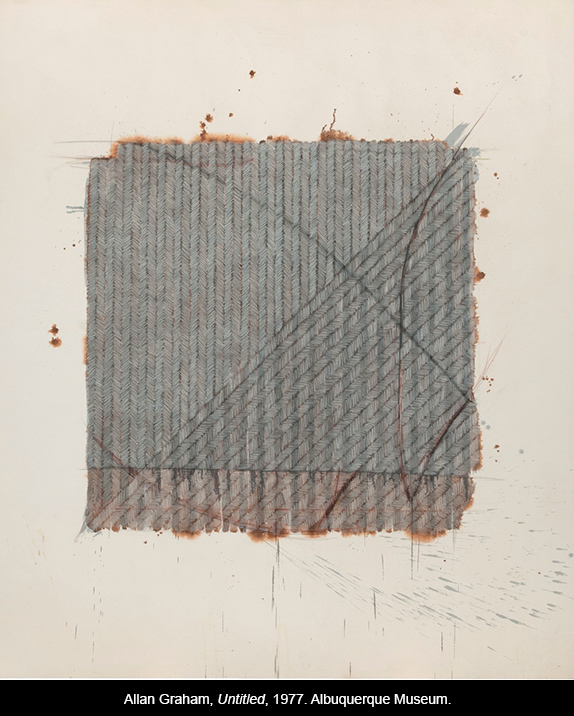

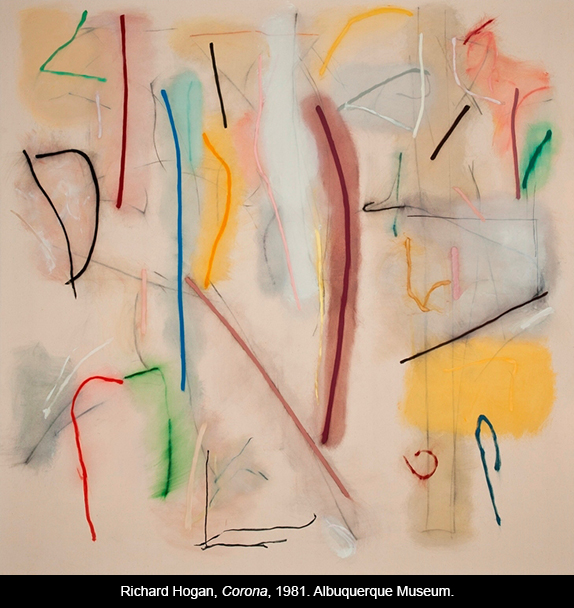

A freer approach to abstract painting could be seen in the works of Allan Graham and Richard Hogan in Visualizing Albuquerque (and that of Terry Conway, had he been included). Graham used the tight grid of a closely marked herringbone pattern (based on woven Japanese mats) as a foil for the linear sweeps of his freehand drawing and spontaneous splashes of wash. Originally inspired by his experiments with a holistic grid, the herringbone mats shrank into rough-edged fragments that hold to the surface, reinforcing its flatness against the more open gestures.

Hogan’s painting, Corona, 1981, is unfortunately reproduced wrongly in the show’s catalog. Shown resting on its right side, the reproduction destroys the sense of the painting, which is entirely based on paralleling the vertical orientation of the viewer who stands in front of it. In its proper orientation, Hogan’s painting is composed of separate marks that are dominated by the vertical, but they remain separate and spontaneous gestures, like place markers, made in response to the field of space that seems to open out within the neutral surface. Drawn in chalk-box colors, and often rubbed out and re-struck so that they leave a halation of color around them, Hogan’s marks alternate between hesitancy and certainty. At once tenuous and affirmative, they declare their independence and separateness as a shared condition, echoing that of the painting’s individual beholder.

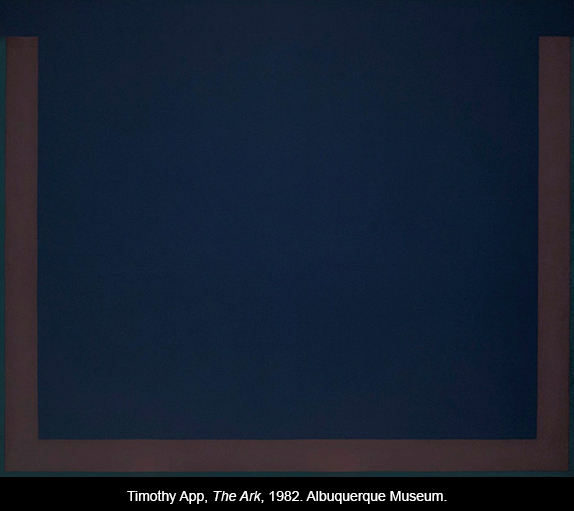

Timothy App’s The Ark, 1982, is a masterpiece of holistic painting, produced with a minimum of means. Austere and silent as a Carthusian monastery, its quietly subdued colors converse in whispers across a vast open architectural space that resonates with a mysterious spiritual presence, and its simple banded border, left open at the top, becomes like a vessel brim-filled with wine-dark liquid light.

More light-hearted, but equally as masterly in its concern for the framing edge, Lucy Maki’s Tulip, 1988, moves the idea of the self-contained painting into a playful dialogue between object and illusion, and pits a bold sense of structure against a feminine delight in decorative nuance. The dialogue between self-contained painting and sculptural object takes a different turn in Constance de Jong’s The Voyager, 1986, which juts laterally along the wall like the stately prow of a ship while its wedge-shaped black planes shift back and forth in three-dimensional space and its edges of polished copper cast a warm reflected glow, as if lit from within.

One final note on the importance of the universities for American artists: By mid century, universities had become the modern Medici. They would provide refuge and reliable financial support for artists where the society at large did not, and they created an environment that encourages individual development. In a university setting, artists could take intellectual and formal risks that would rarely be supported in the marketplace. This is one of the reasons that artists want to attach themselves to universities, and it is a large factor in the influence that UNM has had on the direction of art in Albuquerque.

Nevertheless, there is a deeply conservative strain in Albuquerque’s make up as well, holding onto an imagined past and devoted to a form of “traditional” art that had already become dated by the end of the Victorian era. I recently worked with Garo Antreasian on a book about his career to be published this fall by UNM Press. In his memoir, Garo relates an experience that may have been the breaking point between the city’s traditional artists and the University:

Back in Albuquerque, an event occurred during the mid-1960s on the local art scene that needs to be mentioned, as it reflects the artistic climate of the times and the tensions that existed between the complacency of the established interests and the academic support for artistic innovation and forward thinking at the university. It took place during the New Mexico Arts and Crafts Fair, which was an annual event held in Old Town in the 1960s. I was invited to be one of the jurors for the 1965 exhibition, along with Bob Ellis, a colleague at UNM who was newly arrived from the Pasadena Art Museum, and Elmer Schooley, who was the chairman of the art department at New Mexico Highlands University. The organizers and regulars expected that the usual popular group of perennial winners would walk off with the top awards. But we unanimously and unknowingly rejected many works by these all-stars from the show, choosing much more adventurous and innovative submissions instead. Afterward, there was a huge uproar among the traditionalist artists and their supporters. We were labeled insensitive outsiders, and the local newspaper played up the story. Our colleagues at the university supported our actions with letters to the editor, but there were also letters in bitter complaint from prominent townsfolk. Unforeseen from either side, a rift occurred between “town and gown”—between the traditional town artists’ set and the university crowd—that was harmful to the university and took many years to heal.

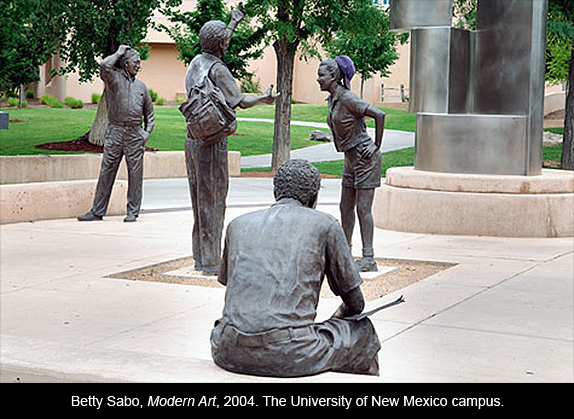

In the end, the conservative forces got their revenge some forty years later, when, in 2004, one of the most dedicated, locally revered, and politically active of the traditionalists, Betty Sabo, managed to get her metal sculpture group called “Modern Art” officially installed in front of the Fine Arts Building on the university campus. The building houses the university’s Music, Theater, and Dance Departments as well as the University Art Museum. But it also houses Popejoy Hall, which serves as the premier theatrical and concert venue in the city and is attended by the entire Albuquerque community. In collaboration with Gary Beals, who provided a pseudo-modernist sculpture as its focal point, Ms. Sabo produced a tableau of Norman Rockwell style figures embalmed in bronze, who appear to be scratching their heads and engaging in a cracker-barrel debate about the “modern art” in their midst.

Now, it must be acknowledged that through her community service and charitable work Betty Sabo has been a significant figure in the Albuquerque art world. It was largely through her efforts that the Museum obtained the magnificent Albuquerque High School collection containing major works by such artists as Ernest Blumenschein and Oscar Berninghaus. She, too, was a product of UNM’s art department around 1950, and she studied technique privately for many years with Carl von Hassler. Consequently some have wondered why she was not included in Visualizing Albuquerque. But her painting, and in her later years her sculpture, was wholly committed to a craft style of anecdotal illustration based in the professional and utilitarian efforts of the so-called “little Dutch Masters” of the seventeenth century, who recorded aspects of daily life. The popularization of the Kodak (and later digital recorders and iPhones) robbed this enterprise of everything but its craft dimension. It’s now a hobbyist’s pursuit that simply has no more than sentimental resonance in the modern world.

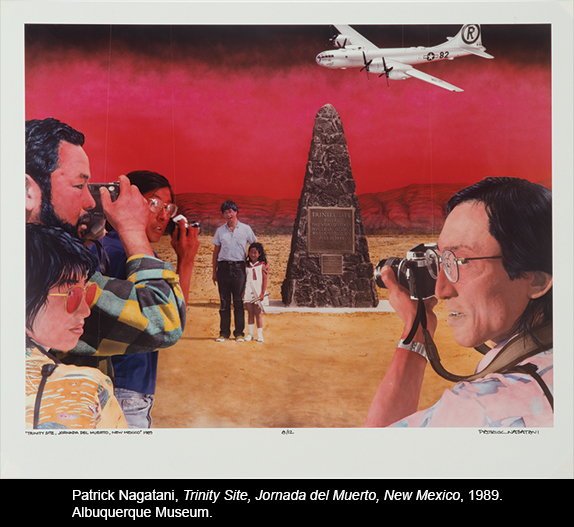

While Sabo’s “Modern Art” sculpture is an all-too earnest attempt to address the puzzlement of artistic change, its innocent backwardness of form and simple-minded conception make it an embarrassment in the university setting. It might be worthwhile to compare Sabo’s sculpture with Patrick Nagatani’s Trinity Site, Jornada del Muerto, New Mexico, 1989, an image from his photo-based series, Nuclear Enchantment. Both offer a similar tableau arrangement of gawking, everyday spectators that incorporates us viewers as bystanders. But Nagatani, a longtime professor of photography at UNM, takes a critical view of the human frailty behind mindless spectatorship, and his desire is to raise consciousness about this pervasive attitude toward the world. His image features a group of mostly Japanese tourists robotically posing to have their picture taken at the Trinity site monument, cameras snapping away. The artist himself is behind one of the cameras, his eye rolled back comically to catch ours and to implicate us in the scene while also indicating that the whole tableau is a highly artificial and ironic concoction. An exaggerated redness of radiation suffuses everything, and although the Japanese are the world’s only direct victims of the atomic bomb, here everyone behaves like typical tourists, driven by mere sensationalism to record or be recorded, while seemingly unable to acknowledge the full historical meaning of the place of their posing. But the camera is an instrument of aggression, and within the ritual of posing they’ve become subjects—subjected to the camera’s invasive victimization, just as earlier unsuspecting residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been subjected to the bomb.

Nagatani’s ironic satire is certainly more sophisticated than Sabo’s. Yet I have to say that in this instance I don’t think Nagatani’s art manages to get very far beyond the trivialities that it attempts to expose. Once you’ve got it, it doesn’t seem to reward repeated viewing, and eventually its exaggerated stance becomes merely annoying. This is a problem with much of the politically conscious art that curator Joe Traugott selected for Visualizing Albuquerque. It can have the character of a good one-liner. But art hangs around for a long time, and who can bear to hear the punch line of a joke repeated endlessly? However, this is not the case with other plates from Nagatani’s Nuclear Enchantment series, such as the one chosen for the cover of the show’s catalog, which is a far more ambitious and enigmatic exploration of the uses of the photographic medium and the elusiveness of the information it purports to provide.

There’s no need to dwell on the fact that a great deal of the art produced in Albuquerque is of limited ambition, provincial and even backward in what it is attempting to accomplish. (To paraphrase Jesus, although with an admittedly un-Christian and non-PC twist: modest talents, like the poor, are always with us.) Nevertheless, there is a surprising amount of adventurous art being done here in a wide variety of media, much of it attaining a high level of achievement. But it is also highly individualistic, which is only to be expected given the stubborn independence and self-sufficiency that is required of anyone who elects to stay on and to persist in doing creative work in The City Indifferent.

Responses to “Unfolding Art in Albuquerque, Part III”