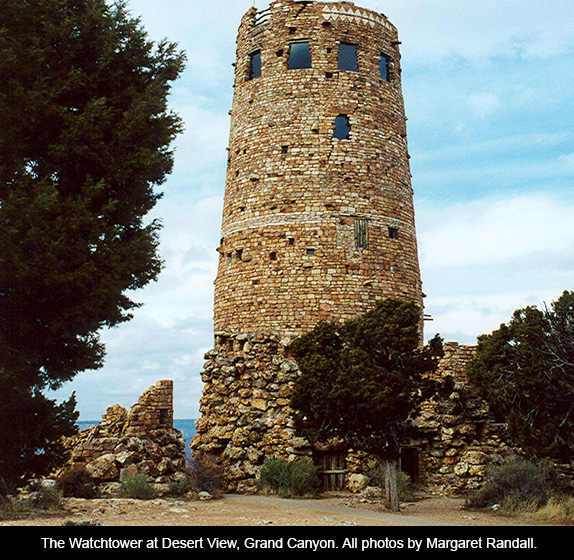

Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter was one of the country’s great architects, at a time when most architects looked to Europe for inspiration and almost no architect in the United States was a woman. To the great delight of those of us who live around here and care about such bounty, she left many of her beautiful buildings in the US American Southwest. None is more breathtaking than the Watchtower at Desert View, on the southeast rim of Grand Canyon.

When Colter started out there was a single school of architecture in the country. It was in Oklahoma. She didn’t study there. In fact, she was fortunate to have a couple of years of art school in San Francisco. From a poor family, her father wanted her to learn something more practical that would insure an easier living. It was his early death that opened her horizons. Her mother recognized her passion and allowed her to study art.

Colter’s big break came when she apprenticed one summer to Fred Harvey, whose company was just then establishing a series of railroad hotels as the dawn of train travel began bringing tourists west. Harvey was immediately impressed by young Colter’s ability and imagination. He hired her on as his lead architect, and the rest is history, a history only told fairly recently in Mary Colter Architect of the Southwest by Arnold Berke (Princeton Architectural Press, 2002). Before this book, there was only one rather superficial biography, Mary Colter: Builder Upon the Red Earth by Virginia L. Grattan. It pays sketchy attention to Colter’s life, but doesn’t say much about her work.

As tourism in the West increased in the 1930s, every important railroad stop acquired its hotel. Colter adapted each to its surroundings, using local materials and highlighting the unique Southwestern cultures. Native artists and artisans often sold their wares close to the train platform. Hotel restaurants became adept at serving delicious full-course meals in the half-hour or so the train would be at the station. (These restaurants were known for their generous portions of pie: each whole pie was cut in quarters!) The famous Harvey Girls waited tables in their starched white shirtwaists and ankle-length black skirts covered with white aprons. The aura surrounding them resembled the aura that would envelop the first airline stewardesses twenty or thirty years later; both jobs were highly romanticized and required good looks, decorum, and single status. Many young unmarried women from the East competed for the job.

I have often bemoaned the fact that Albuquerque’s Alvarado was torn down in 1970: a shortsighted decision the city would live to regret. But Albuquerque was not unusual in this respect. As train travel gave way to flight, many of the old railroad hotels met similar fates. Alone among them, La Posada in Winslow was saved from destruction when it became the northern Arizona office building for the Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe. La Posada was Colter’s favorite hotel. I have written in these pages about the successful efforts made by the couple who bought, renovated, and runs that hotel today.

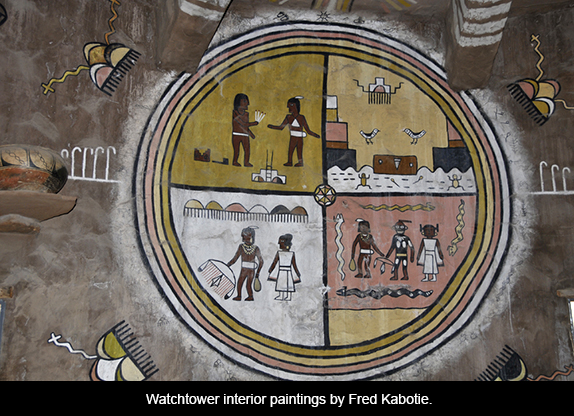

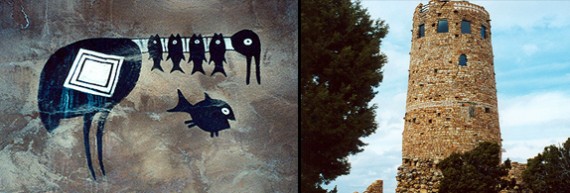

Those creations by Colter that were able to survive the seventies erasure include a number on Grand Canyon’s South Rim. The natural wonder itself insured a steady stream of visitors long after railway travel subsided. Colter built and decorated Bright Angel Lodge and Cabins, Hopi House, Lookout Studio, Hermit’s Rest, and Phantom Ranch nestled in the Canyon’s depths. But her most spectacular building in the Canyon environs—perhaps anywhere—is without a doubt The Watchtower at Desert View. Neither hotel nor restaurant, nor even primarily a gift shop, it stands simply and proudly as a testament to her love of the land, knowledge of and respect for indigenous cultures, capacity for careful research, and recognition of some of the great Indian artists such as Hopi Fred Kabotie, whose haunting work she brought to national prominence.

Colter went to work on the Watchtower right after finishing La Posada, and finished the spectacular building in 1932. By the mid-twenties train travel actually began to diminish at the Canyon, but by then its fame was assured. Travelers began coming by car, and each year saw a healthy increase in visitors.

The Watchtower rises 70 feet above the rim some 25 miles east of Grand Canyon Village. It is the only building that can be discerned from the Canyon floor. Colter flew over the Four Corners region and observed the ruins of small watchtowers still visible; she had also seen the towers at Canyon de Chelly and elsewhere. The round tower at Mesa Verde’s Cliff Palace comes to mind. Although she didn’t model The Watchtower on any of these in particular, they inspired its conception.

One also thinks of the towers at Hovenweep. The Watchtower’s base is intentionally rough, resembling rubble or the natural stone outcroppings upon which the Hovenweep towers were built. There is a sense of it being firmly planted on the earth, not so much imposition as continuation. With the Watchtower, Colter was telling stories—using form, content, and location as her language. Her creation at Desert View is stagecraft, history lesson, and spiritual experience.

Mary Colter didn’t believe that her work ended when a structure was complete. She had precise ideas about how it should be represented to the public, what narrative should accompany it, the connections that needed to be made. She was a hard taskmaster, and it was often rumored that her workmen resented the detailed labor she demanded. At Bright Angel Lodge, for example, she asked that boulders be hauled from the Canyon’s various rock strata, and used in just that order in the construction of one of the great fireplaces that became her signature feature.

I know of the existence of The Manual for Drivers and Guides: Descriptive of the Indian Watchtower at Desert View and its Relation, Architecturally, to the Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest, a guide written by Colter to be used by those taking early visitors through the Watchtower. Unfortunately only 100 copies are said to have been printed, and I have yet to get my hands on one.

Arnold Berke points out that “the similarity, to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum, in both design and use, is striking.” I have long wondered who influenced whom, especially with regard to the use of local materials to blend buildings with their natural settings.

Today a curio shop occupies The Watchtower’s ground level, replete with the range of tacky to more interesting souvenirs, and even some museum quality pieces, purchased in volume by the more than five million people who visit Grand Canyon each year. Since the average stay is 15 minutes—yes, 15 minutes!—it’s safe to say that very few of those visitors even get to The Watchtower, which is quite a bit off the beaten path.

But it’s the Tower’s upper levels that captivate. By way of narrow circular staircases, and gripping bannisters still wrapped with the original rawhide, you ascend from one floor to another. There are a total of four, each richly painted by Fred Kabotie whose murals alone deserve long contemplation. Fred Greer’s petroglyph-like imagery is also bewitching. There’s always someone who wants to disrespect extraordinary art; in 2008 two tourist were banned from all the National Parks for a year after applying whiteout and permanent marker to correct (deface) the punctuation on a sign at the Watchtower that had been painted by Colter herself.

The circular ceiling is the building’s crown jewel: a sort of indigenous Sistine Chapel. Two terraces open to sweeping Canyon views.

Colter undoubtedly chose this spot with those views in mind. Here you look down river, the multi-hued buttes and other formations spreading out on either side. But she wasn’t satisfied with the overall view. She placed small windows—some of them square and others irregular in shape—in strategic spots along the walls. These, and odd wooden boxes that border one of the terraces and reverse the image, frame singular views she must have considered at length.

Snippets of conversation from the numerous visitors reveal surprise and delight. Even when comments are uttered in a language you don’t understand, the tone and inflection indicate something of what is being experienced.

In the upper echelon art and architecture world of today we sometimes get to admire a monument or edifice whose only reason for being is to bestow wonder. The Watchtower is such a building. It enhances a natural land feature one might think could not possibly be enhanced. It embraces the ancient as well as a profound sense of timelessness. It simply is. And within it, you feel the ways in which Colter was connected to this land, this place, this unique spot on earth.

Desert View Watchtower was designated a United States National Historic Landmark as part of the Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter Buildings collective nomination on May 28, 1987. This nomination comprises the Watchtower, Hopi House, Lookout Studio and Hermit’s Rest. The tower is also part of a National Register of Historic Places historic district, the Desert View Watchtower Historic District, designated on January 3, 1995.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Mary Colter’s Grand Canyon Gem”