It isn’t often that a bygone era can be recreated organically, with authenticity and style. Too often we get a Las Vegas or Disneyland version of a previous moment in history. La Posada Hotel, in Winslow, Arizona, allows us to go back to the 1930s and ‘40s, when the railway was opening the American West, and enjoy one of that era’s iconic lodgings. It also brings into focus Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, main architect for The Fred Harvey Company, to whose genius the Southwest owes so much.

Mary Colter was an architect at a time when few women entered that profession. She was a designer whose ideas about natural materials and sensitivity to the great Indian artists of the time marked her work in very unique ways. Harvey’s confidence in her and his ability to invest gave her the perfect palette for her ideas. She designed many of the early railroad hotels—at Grand Canyon, here in Albuquerque, and elsewhere. Albuquerque’s Alvarado was torn down in 1970, a tragedy for the city. Other of her hotels also disappeared around that time; rail travel had been replaced by the airplane, and fewer tourists were using the trains.

La Posada, in Winslow, escaped this fate through a series of fortuitous circumstances. It was Colter’s favorite project, but she finished it in 1930 just in time for the Great Depression. It never did well, and closed in 1957. Its beautiful murals were painted over and its period furnishings were sold off or destroyed. Rather than tear the building down, however, the Santa Fe Railway decided to use it for its northern Arizona offices. Grand halls were converted into office cubicles; luxuriant gardens became a parking lot. But at least the building itself was preserved.

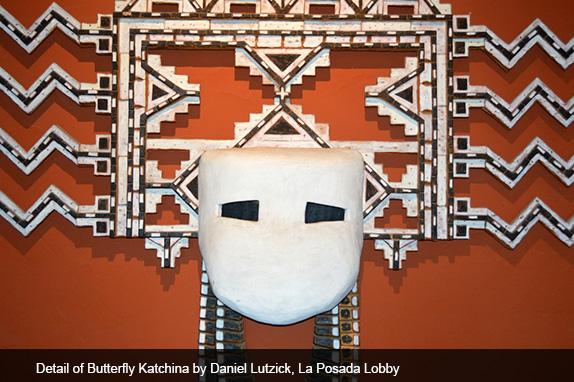

When Allan Affeldt and Tina Mion learned from the National Trust for Historic Preservation that La Posada was in danger of being demolished, they raised the money to buy the property in 1997. A third partner, Daniel Lutzick, joined the endeavor. From then on, they devoted themselves full time to renovating the building. Affeldt and Mion actually reside on site, and Lutzick has an art gallery down the street. Day by laborious day, they have brought back the guest rooms, exhibition halls, dining room, and gardens. La Posada continues to be a work in progress. Mion is also an artist, and her paintings adorn the walls, along with pieces by others. Master carpenters are still creating furniture reminiscent of that which Colter commissioned for the hotel.

Most of us want to return to an inviting hotel because of its location. It sits in the mountains or by the sea, is on the rim of Grand Canyon or in New York’s theater district, or its climate is particularly suited to a delicious getaway. Winslow, Arizona is none of these. It is a small dusty town off I-40 between Flagstaff and Holbrook. True, one can use it as a base from which to explore nearby Homolovi or Wutpatki ruins, the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest. And La Posada is more than a hotel. Its renovators conceive of it as a community-building project. They have set up the Winslow Arts Trust (WAT), which contemplates a Route 66 Museum, Snowdrift Art Space, and other local spots important to the area’s cultural history.

At La Posada there is much to admire, and also much to imagine—from Colter’s presence at the site. Half the fun is “remembering” what Winslow must have been like when the original hotel existed. Cadillac and Lincoln long cars would have been parked near the door, and guests would have embarked on the famous “Indian Detours” promoted by Fred Harvey to acquaint easterners with the people who inhabited –and still inhabit—this land. The concept was admittedly contrived, but visitors at least obtained some familiarity with the area.

Winslow was once an important transportation hub. Not only did the Santa Fe Chief stop there, but the town was a TWA destination as well. Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow stayed at La Posada during part of their honeymoon, and again when Lindbergh designed Winslow’s airport, the world’s only surviving Lindbergh-designed airport. Albert Einstein, Will Rogers, Diane Keaton and many other celebrities stopped in Winslow, either during the hotel’s first incarnation or its current one.

At the height of its initial glory, La Posada welcomed guests arriving by train. The Chief, with its luxurious dining car, gave travelers a taste of Colter hospitality with her Mimbres decorated tableware. Or travelers could leave the train and eat at the hotel’s Harvey House, staffed by the famous Harvey Girls in their long black dresses and white aprons. They prided themselves in serving a hot meal in a half hour, so passengers could board again in a relaxed manner. One of Harvey’s featured items was its pie; each serving was one-quarter of the whole. Today’s excellent Turquoise Room restaurant continues the tradition of offering a quarter of a pie per serving. But the rest of its menu is more sophisticated.

Today at La Posada a stay of a night or two is well worth stopping in Winslow. Many travel magazines and guides list the hotel as one of the best modestly-priced in the country. Just as many restaurant guides list The Turquoise Room (owned and run separately from the hotel) as one of their favorites. Simple comfortable rooms have all the amenities—including normal-sized shampoos and lotions (none of those tiny hotel samples). Décor is eclectic Southwest, with a nod to Mary Colter’s eye for fine art. Sunken gardens and large expanses of lawn offer quiet places to read. A croquet game was going on the south lawn when we arrived. A maze, constructed of bales of hay, provides an interesting diversion. And books are everywhere: in the guest rooms, in the reading rooms and lobby.

For me, though, the delight of our stay was hearing the trains roaring by, especially at night. Between 97 and 104 pass in any 24-hour period. Most are freight trains and don’t stop. An Amtrack passenger train stops twice daily, once going east and once west. The woman who took my telephone reservation warned me that our room was “on the train side,” but added that they provide earplugs for guests who may be bothered by the noise. I was lulled to sleep by the sound of the trains, and woke only when I realized one hadn’t passed in a while.

This was the first time we had stayed at La Posada, although we had stopped there a number of times in the past to eat. The Turquoise Room deserves special mention; its menu is creative and delicious. The waitresses wear a modified Harvey Girl outfit, with pants or a short skirt replacing the long black uniform but with a similar white apron. My favorite dishes are any that include the chef’s signature sweet white corn tamales. My partner had a meat-lover’s plate this last time around, combining buffalo, elk, and quail. She’s still talking about it.

Responses to “The Hotel That Came Back from the Dead”