If we had even a modest education, it was almost certainly a Western one. Depending on whether we studied at private or public schools, or in the latter case were lucky enough to attend one in which the teachers tried to give us their best, when we studied ancient Greece our lessons included some talk of the most famous Greek Gods. We are much less likely to have learned Khmer or Maya or Aztec mythology, which is a shame because those cultures, so much closer to home, are equally rich in the stories ancient peoples invented to explain their worlds.

If we studied Greece, it was most likely a superficial overview. We probably covered some of the main gods—Zeus, Apollo, Athena, Dionysus, Hermes—ignoring the vast roster of other deities, titans, giants and other magical figures. It would have been useful had we learned that almost every culture’s pantheon of gods and goddesses mirrors every other culture’s roster; their names are different but the powers with which they are imbued and the roles they play in shaping our destinies match up amazingly well.

I received a public school education here in Albuquerque, fairly typical for the period between World War II and Vietnam. Being a girl, they didn’t think it important that I learn math or science. Not until 1957, that is, when the Soviets put their Sputnik into space. Then the contest was on. But by that time I had finished high school. Great literature—even what contemporary literature we studied—was taught mostly by rote, and history and culture were as well. And although I remember brief mention of the most important Greek gods and their myths, I wasn’t able to relate them to my own life in any meaningful way.

I first realized the similarity between the gods worshipped in one culture and those worshipped in another when I lived in Cuba in the 1970s. The revolution didn’t pay much attention to the African gods brought over on the slave ships, nor did it allow much space for the Christian saints. But living among the Cuban people, I quickly came to understand that Saint Barbara and Chango were one and the same: two patrons of two different cultures, both fighting for recognition in a single rapidly changing society. Different ancient cultures explained their world in different ways, assigning personalities and powers to a pantheon of gods and royal figures. Later, when the Cuban revolution became more tolerant of religion, many artists and poets understandably began producing faith-based work.

It wasn’t until many years later, when I began to travel, paying particular attention to some of the sites where ruins of the great civilizations existed, that I began to be able to understand the roles played by the gods and goddesses in those disparate cultures, and how they could so often be likened to those worshipped elsewhere.

Satellite imaging has revealed Angkor, in present day Cambodia, to be the largest pre-industrial urban center in the world. There, and in much of the rest of Southeast Asia, Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism alternated from one period to another. The great ruined cities were built by local kings, who gave themselves supernatural powers. For example, Jayavarman II resided for some time in Java during the reign of Sailendra, Lord of Mountain. Some believe that the concept of Deva Raja or God King was imported from Java. For a time, the God King allegedly ruled over Java, Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula and parts of Cambodia.

Closer to home, in the Mayan city states of Mesoamerica (today southern Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and parts of El Salvador), kings also ruled centers of power during the height of the Maya civilization. These flesh and blood kings acquired divine attributes, and there was a great deal of syncretism between royalty and gods. Quetzalcoatl, or the feathered serpent, was one of the major deities of the ancient Mexican pantheon. Representations of a feathered snake occur as early as the Teotihuacan civilization in the 3rd to 8th centuries of our era. Quetzalcoatl seems to have been conceived as a vegetation god, an earth and water deity closely associated with the rain god, Tlaloc. I have written about visiting a colonial church in Cholula, Mexico, and being surprised to find an unmistakable image of Tlaloc among 260 baroque heads of Christian saints covering the underside of the main cupola.

All these cultures had female deities as well. Lady Jaguar Shark was a queen with divine powers whose reign is documented in hieroglyphs and stelae at the Guatemalan ruins now known as Tikal. Coatlicue, the ferocious figure of the woman with a skirt of serpents, is the Aztec goddess of Earth, believed to have given birth to all celestial things. Most Aztec artistic representations of this goddess emphasize her deadly side, because earth, as well as being a loving mother, was considered the insatiable monster that consumes everything alive. Coatlique ate her own children. She was the devouring mother, in whom both the womb and grave coexist. Her imposing figure can be viewed today in the main exhibition hall of Mexico City’s Museum of Anthropology and History. I have always been fascinated by Coatlique.

I could go on, listing gods and goddesses from every known culture, and pairing them with their counterparts. But I want to get back to Greece. I finally traveled there in 2004, armed with the scant knowledge of Greek mythology I had somehow picked up from my years in school and what I had read since. Somewhere beneath the surface of my consciousness, I think I wanted to run into Athena, Goddess of intelligence and skill, or Demeter, Goddess of grain, agriculture and the harvest, growth and nourishment, in their modern-day incarnations. I wanted to meet Hermes, God of boundaries, travel, communication, trade, thievery, trickery, language, writing, and diplomacy, and have the courage to ask him why he represents both language and thievery. I wanted to understand how contemporary Greece, one of the nations pulling the European Union apart, lives its ancient myths in the midst of the present day demonstrations flooding the streets of Athens. And if those myths offer solutions to the problems of poverty, injustice, corruption and imposed austerity.

We flew to Athens, where we climbed Acropolis Hill and looked down on the Agora where Socrates once walked. I felt my body tremble slightly, as I imagined myself in conversation with the great teacher. The Socratic model of education has long seemed insuperable to me. Deep in a modern subway station, I saw a glassed-in wall protecting the many layers of earth that had been revealed when subway construction took place. Here were burials and utensils from everyday life, artifacts and other objects in a map upon which travelers could gain glimpse some sense of earlier times.

We traveled north to Meteora, where we visited several ancient monasteries clinging precariously to jutting rock. A part of this area of the country is still off-limits to women: a world of men. Although admittedly operating through a tourist lens, throughout Greece I felt the weight of male chauvinism in glances, attitudes and comments. At the same time, I learned that much Greek law is favorable to women’s rights. Aphrodite, Goddess of love, beauty, desire, and pleasure, caught me off guard on more than one occasion. But Zeus, king of all the gods, ruler of Mount Olympus and God of the sky, weather, thunder, lightning, law, order and fate, was ever present.

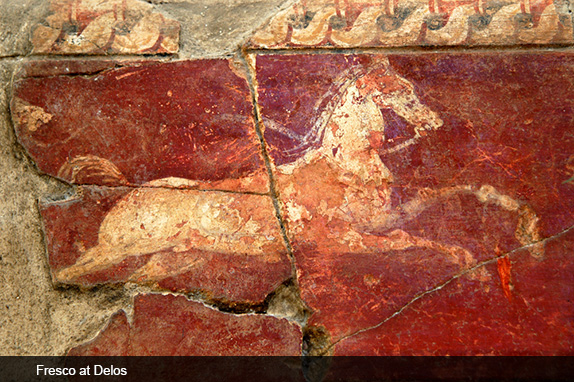

I found the strength of Greek women most palpably on the island of Santorini, where a small museum of Minoan culture displayed a few frescoes as well as ceramics and objects wrought in gold. In the frescoes I saw large-boned Minoan women working in the fields and going about their daily activities. They reminded me of the Amazons. Some wore brightly patterned clothing but their pendulous breasts hung naked and unashamed. Later that same day, a woman showed us around the grape fields, cellars and tasting rooms of a winery proud to describe how it applied modern methods to an age-old industry. That night I dreamed I was visited by Phanos, God of procreation in the Orphic tradition. We started to talk, but our conversation ended abruptly.

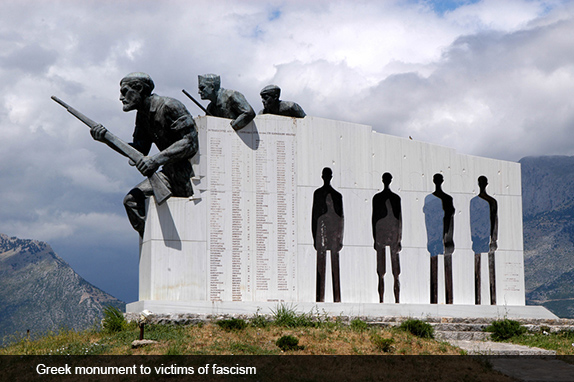

Driving through the countryside one day, I came upon a monument to Greek partisans killed by the ravages of European fascism during World War II. The monument made a profound impression. Along with a rather uninspiring cluster of figures of men with guns, and the customary list of names representing lives lost, the bulk of the monument involved simple cutouts of bodies no longer there. Those silhouettes, through which one could view an impersonal landscape of distant mountains and valleys, hit me where it mattered. Sacrifice and death as an absence of life, a nothingness, a warning. Terrifying and entirely appropriate at one and the same time.

Despite the overly touristic nature of most islands’ waterfronts, riddled with T-shirt shops and expensive cafes, I loved ploughing the Aegean Sea on a small sailing vessel called Galileo. We were only a couple dozen on board. Usually we had a day or two at each island, and making our way as far inland as possible brought the enriching experiences of discovering villages where inhabitants worked marble or baked a particular sweet. Windmills in different states of repair or disrepair, dovecotes with their little square windows, and old stonewalls winding their way up hillsides spoke of the authentic Greece.

In many of these island habitats, remnants of ancient ruins proved as interesting as the Parthenon or the underwater harbor at Delos. The ways in which the locals incorporate these sites into their daily lives imbue them with a quality the larger more important ruins no longer possess.

I remembered being a child, six or seven years old, living in a suburb of New York. On weekends my parents or grandparents sometimes took me into the city, and a favorite place to go was The Metropolitan Museum of Art. I was small, so everything in that museum was enormous. My absolutely favorite statue was the Victory of Samothrace, sometimes called The Winged Victory. Headless and armless, she nevertheless exuded an energy I needed. To my yearning girl-child psyche, she personified all the strength and power a woman might have.

Sailing through the Agean, I thought of my childhood heroine. I learned that the marble used to sculpt my winged woman came from the island of Paros. Hundreds of years ago Paros marble traveled throughout the Aegaen on its way to artists’ workshops on other islands. Several years later, perusing the New York Times obituaries, I found one for Dr. Phyllis Williams Lehmann, 91, Archaeologist of Samothrace. That’s how I discovered that she had been one of the archaeologists who dug at the site. Three Nikes, or winged women, were unearthed there. Two, discovered by others, were taken away and sent to European museums. Lehman directed that the one she dug up remain at the ruin, in its little site museum. This was how I put the last piece of my own puzzle regarding Samothrace together: the statue belonging to the Louvre in Paris had been on loan to the Metropolitan for a few years during my childhood.

When we travel we not only take in the sights and sounds of today’s world. We can move beneath the surface and back through time, to worlds whose mythologies shape the one in which we live, no matter where that is. This is one of the reasons it is so important that museums that have acquired pieces of another country’s cultural history—whether legally or illegally—return those pieces to their places of origin. A people is not complete without the living evidence of its life. And that includes its mythology.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Greece”