You can’t write about Grand Canyon; everyone’s written about Grand Canyon. There must be a thousand books out there. What could you possibly say that would be new?

That was me talking to myself.

But myself insisted.

I’ve probably been to the Canyon more than a hundred times since my first trip at the age of nine. We lived in a suburb of New York City, and my parents loaded my brother, sister, and me into their old black Studebaker and drove west, looking for a new place to live. Grand Canyon was a detour of pure wonder on that trip. Several years later, at home in Albuquerque, my father took me down to the bottom on mule back. One of my saddest losses, through the years, was the 8 x 10 taken of our group as we passed just below the rim; the old Kolb Brothers Studio snapped those pictures every day for almost half a century, having them ready to sell as mementos when the happy campers came out of the Canyon the following day. I remember my father wearing a wide-brimmed hat; I had braids.

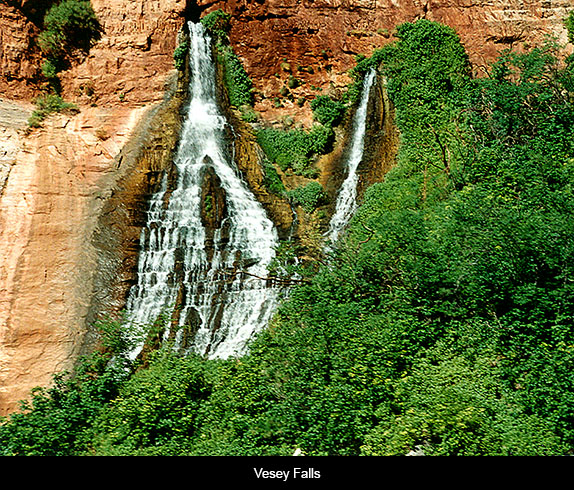

Since then, Grand Canyon has been a favorite retreat. I’ve driven to both rims dozens of times, taken one of my own children down by mule, hiked to Indian Gardens and out to Plateau Point, explored 277 miles of the Colorado River in a little wooden dory, and made pilgrimages to every one of Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter’s innovative buildings that so eloquently speak its language of age and rock.

When my partner of 26 years and I got together, we went over to Grand Canyon to spend a couple of days. A few nights before, Mary Colter had come to me in a dream. She told me we would find the matching rings we wanted there. And we did find those rings at Hopi House, the unique studio/trading post Colter designed and built in 1905 so that visitors to the Canyon could observe Hopi artists at work. Hopi House is no longer a place where one can see working artists, but its museum quality jewelry is always worth an hour or two.

I’ve been back to the Canyon with my parents, relishing their enjoyment of the place in the last few years they were able to travel before they died. I’ve taken every one of my four children and most of my ten grandchildren, and in every season. Seven easy hours’ drive from Albuquerque, Grand Canyon is always a good destination for a satisfying getaway. It has changed immensely over the years. Not the Canyon itself, of course. Despite the old joke about filling it with used razor blades or the more serious attempts to dam the Colorado or run a railway through its corridor, destruction of the natural wonder hasn’t been possible.

What’s changed is the nearby Indian peoples’ relationship to the land, the human community around Grand Canyon, the National Park Service’s ability to cope with its huge numbers of visitors; a succession of commercial concessions’ solutions to the requirements of traffic, lodging, gift shops, and food; regulations aimed at most expediently organizing parking around the lookouts and the way no small number of serious emergencies are handled. A ranger’s detail at the Canyon is still a prized post, and summer employment waiting tables or cleaning rooms draws young people from around the world. In 1919, the earliest year for which records are available, Grand Canyon attracted almost 38,000 visitors. With only brief dips during the Depression and World War II, the number has steadily risen to today’s 4 and a half million a year.

Several Indian tribes live nearby, or hold territory adjacent to the park. Navajo lands extend out from many points along the south rim. The Navajo people believe the spot where they emerged from the third into the fourth world is along the river, and several river guides, as a sign of respect, cautioned us not to look when we passed that spot. The Havasupai live in beautiful Havasu Canyon, a large tributary on the south side of the Colorado River that veers off from the main canyon but does not lie within national park boundaries. It’s a strenuous hike down to their village of Supai and the magnificent falls beyond, but several thousand people a year make it. The Hualapai people also lay claim to land within the Canyon corridor. They have their own one-day river rafting business at its western extreme, and have built The Skywalk, a horseshoe-shaped steel frame with glass floor and sides that projects some 70 feet out from the rim. There is a great deal of disagreement as to whether this is a legitimate attraction or a denigration of the environment that nevertheless brings revenue to the tribe.

The United States has more, and more expertly run, national parks than any country I know. Currently there are 59, ranging from the system’s stars—Yellowstone, Denali, Glacier, Bryce, Mesa Verde, Yosemite, Everglades, and Grand Canyon—to many smaller sites. Most have something for everyone. Although a few of the major parks, such as Canyonlands, have no lodging within their boundaries, in most of them well-kept campgrounds welcome those with tighter budgets or simply want an experience more immersed in nature. Those desiring greater comfort or luxury can find it in historic lodges. In between, there is a broad range of hotels, cabins, and hostels.

Grand Canyon has more variety in this respect than almost any other park. Rooms in every price range dot the busy south rim, and lodges and cabins care for visitors at the much less visited north rim. Just outside the south rim’s canyon village, overflow crowds can generally find a place to stay in Tusayan, Flagstaff or even Williams. One can reach the Canyon by train as well as car. River traffic ranges from commercial trips using large inflatable rafts (some rowed, some motorized) to commercial dory trips and a small number of independents sportspeople who enter a lottery for the coveted permissions.

One of this country’s greatest bargains is our national park entrance fee. The larger parks, such as Grand Canyon, charge $25 per carful per day. But those who frequent these glorious sites can buy yearlong multiple-entry passes for $50. And the best deal of all is the Golden Age pass: for just $10 anyone 60 or older can purchase a lifetime credential allowing the bearer and all those accompanying him or her access to any park or national monument in the system for as long as the bearer lives.

This is about Grand Canyon, though, its breathtaking beauty and enduring mystery, its fascinating history and idiosyncratic stories.

Native peoples who lived in or passed through what is now north central Arizona must have stumbled across the Canyon’s dramatic landscape long before it gained national recognition. We have no record of their travels but can imagine their astonishment. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, on his 1540 quest to find the mythic “seven cities of gold,” was the first European to view the Canyon. In 1869 Civil War General John Wesley Powell, an intrepid one-armed explorer and geologist, led a three-month expedition on the Colorado believed to be the first to make it all the way through the corridor. His diary is worth reading for anyone interested in Canyon lore or early American adventure.

It wasn’t until the beginning of the 20th century that adventurers, photographers, and entrepreneurs began coming to the Canyon in significant numbers. German brothers Elsworth and Emery Kolb built a studio on the south rim and lived there for decades; their negative collection is at the University of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, and their home is now a bookshop and gallery. A young honeymooning couple named Glen and Bessy Hyde tried to row the Colorado through the Canyon in 1928. Their empty boat was found intact, but Glen and Bessie were never seen again. Rumor has it she murdered him and somehow escaped the rigorous terrain. But no bodies have ever been found. A river guide told me that in the 1980s a woman on one of his trips claimed to be Bessie Hyde. Her story was intriguing, her age about right, but she ultimately refused to cooperate with an investigation that might have closed the case. It remains, like so much Grand Canyon lore, a part of its complex legend.

There are hundreds of legends about Grand Canyon, some of them true, others richly embroidered, still others outright tales. All say something about the place and many have been anthologized. There are books about the river, about hiking Grand Canyon, and collections of personal stories of canyon meditation and reverie. There is a wealth of poetry and art. There is even a book about deaths at Grand Canyon (Over the Edge by Michael Patrick Ghiglieri and Thomas M. Myers). Sadly, many choose the Canyon as a suicide site, but many more fall accidentally when they venture off marked trails or succumb to sunstroke or dehydration if hiking without sufficient water.

A legend that has always intrigued me is the one concerning William Dunn and O. G. and Seneca Howland, three members of Powell’s expedition. Exhausted and dispirited, they decided to leave the group at a place now called Separation Canyon. Powell gave them food and guns, but they were never heard from again. For years they were believed to have been murdered by Paiute Indians, and there is a plaque with that explanation at the riverside spot where they parted company with Powell. In recent years a new story surfaced. It was learned that Dunn and the Howland brothers were shot by Mormon settlers who thought they were representatives of the federal government who had come to do them harm. A letter with the truth was discovered in someone’s attic. The plaque was still there the last time I was at Separation Canyon, though. Racist assumptions live on.

The Fred Harvey Company played an important role in developing Grand Canyon so that it could support a future of visitors. The late 19th and early 20th centuries belonged to the railroad. Before commercial airplanes, trains not only carried the country’s major commerce, they were the preferred mode of travel for millions of Americans. The country’s railways helped to open the West. Fred Harvey built hotels, called Harvey Houses, at many of the stations. It was Harvey who took a chance on the very young Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, when US architects were few and woman architects all but nonexistent. She became his chief builder and interior designer, mastering the use of natural materials and making them an extension of their settings long before Frank Lloyd Wright became famous for similar innovation.

For decades, starting in 1878, the Fred Harvey Company operated the hotels at Grand Canyon. Colter’s designs, and her recognition of native artists such as Hopi Fred Kabotie (1900-1986), made her buildings special. Other hotels, designed by Colter throughout the West, were also gems. Here in Albuquerque we had the graceful Alvarado until it closed in 1969 and was thoughtlessly demolished the following year. The 1970s saw the demise of most Colter hotels. The La Posada in Winslow escaped that fate and has since been meticulously renovated.

The Harvey eateries were staffed by the famous Harvey Girls, unmarried white women between the ages of 18 and 30—most of them from the eastern part of the country—who wore starched white shirts, long black skirts that could be no shorter than 8 inches from the floor, white aprons, and no makeup. They were supervised by a “house mother” and forced to observe a 10 p.m. curfew. They earned $17.50 a month (approximately $450 in today’s wages) plus room, board, and tips. It was a desirable job and lent an aura of glamour to the establishments.

When a train stopped at a station with a Harvey House, the restaurant was able to feed all passengers in 30 minutes. And the food was famously good, with hefty portions (pies were cut in fourths, rather than sixths which was the measure of the day). Harvey service also extended to the train’s dining car. Colter designed the dinnerware, using stylized Mimbres motifs. In the early 20th century, with the advent of the automobile, the company prospered by extending its services. In 1926, Harvey Cars were used in the famous “Indian Detours,” taking tourists to more remote areas of the Southwest. Fred Harvey’s legacy continued until the death of a grandson in 1965.

Today, with the exception of Bright Angel Lodge on Grand Canyon’s south rim, most of the hotels no longer exist. Bright Angel has gone through a series of subsequent managements. Since 2004, all Canyon establishments are run by Xanterra Parks & Resorts. In 2006, Xanterra purchased the Grand Canyon Railway and its remaining properties, including the upscale El Tovar Hotel. But the Harvey Girls earned their place in the history of the West. Samuel Hopkins Adams published a 1942 novel called The Harvey Girls. Judy Garland and Angela Lansbury starred in George Sidney’s 1946 musical of the same name. The little known but very interesting Belen Harvey House Museum is only a short Railrunner ride south of Albuquerque. In an original Harvey building visitors can see relics used by the famous girls, as well as a marvelous collection of model trains from the era.

Grand Canyon, despite seasonal overflow crowds (the typical visit averages 15 minutes at the park!), remains one of the all-time great destinations. I am always amazed, especially living so close, how often I meet people who have never been there and have no plans to go. There is something for everyone, from pricey helicopter flights (some years back planes were stopped from flying over the canyon due to noise pollution and accidents) to gentle walks along the rim, hikes part or all the way down, half-day, full-day and two-day mule trips (on the latter people spend the night at Colter-designed Phantom Ranch), and the aforementioned river excursions.

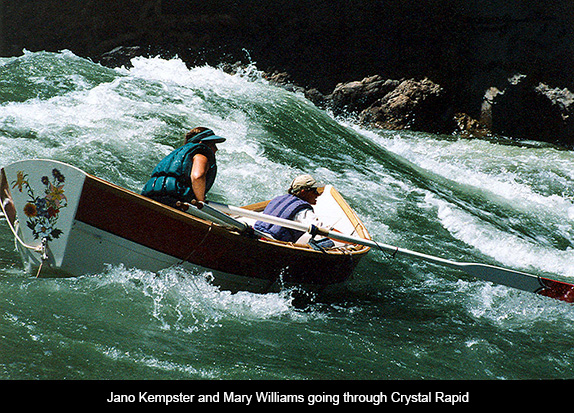

The Colorado River runners have their own fascinating history. Initially, theirs was a world of men. A few rugged prospectors and ranchers designed the first boats, started the companies that offered their services, and made history with their exploits. Names like Nathan Galloway and Don Hatch are legion. Martin Litton made the wooden dories famous, and also played an important role, along with David Brower of the Sierra Club, in preventing a proposed dam on the Colorado. That dam would have destroyed the Canyon. Beautiful Glenn Canyon had already been forced underwater by the 20th century’s greed for development, and Brower and Litton’s 1960s campaign saved Grand Canyon from the same fate.

The first woman to break into the river runner world was Georgie White. After World War II, she invented what she called her G-rigs, by lashing huge Army surplus rafts together and launching pay-as-you-go trips. For the first time, running the Colorado through Grand Canyon became something you could do even if you didn’t have a lot of money. Today, although it’s still mostly a men’s world, third and fourth-generation river runners include a number of skilled women.

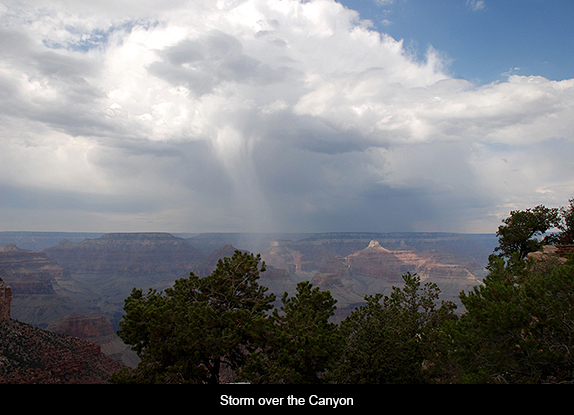

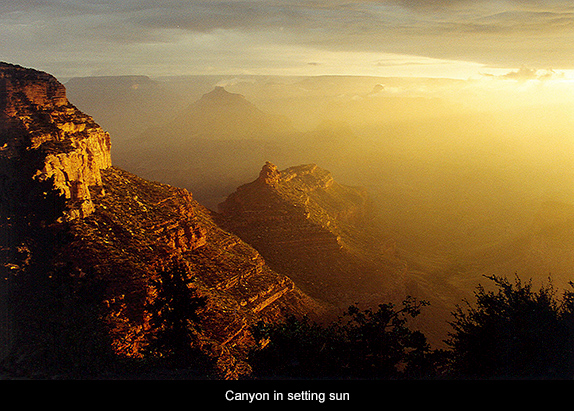

A mile above the river, one can sit on the El Tovar verandah and sip a cool drink while watching the canyon’s colors change in the shifting light. One can appreciate a variety of resident animals, including squirrels, lizards, mule deer, a herd of elk that can often be found nibbling at the hotel lawns in the gathering dusk, and a number of California condors floating on circular currents of air just beyond the rim. And Grand Canyon is different day to day, season to season. Every light works its magic, as is evident in the rich painting and photography the place has generated. Free evening lectures given by rangers versed in the area’s geography, geology, botany and human and animal life can be fascinating. Sadly, beginning during the George W. Bush administration cutbacks in National Park funding has limited these events.

Another “gift” the Bush administration bestowed on Grand Canyon was an incursion of Christian fundamentalist tracts. Grand Canyon is a place where millions of years of the earth’s evolution can be seen in its many strata of rock. It is an open book of evolutionary history. Yet Christian fundamentalists maintain that God created the earth 4 and a half thousand years ago. This makes for quite a contradiction. Such contradictory belief systems can co-exist. River guides have told me that trips taken by those who take the Bible literally generally bring their own “geologists,” so the group may hear a story in line with their beliefs. During the Bush administration, though, at one of the south rim’s curio shops I saw a book on sale that made me shudder. It explained that the Canyon was carved by Noah’s flood. I’ve looked for that book on subsequent visits, and happily haven’t seen it again.

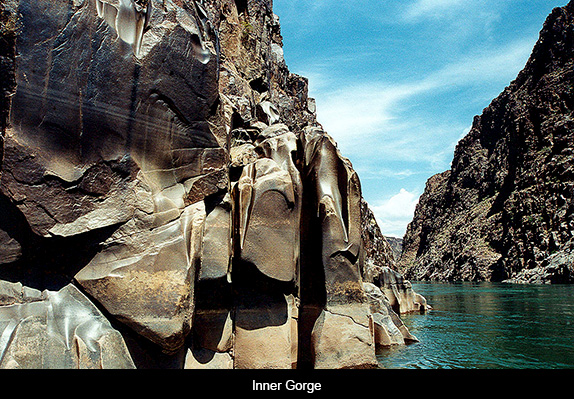

Grand Canyon National Park comprises close to 2,000 square miles. Through it runs 277 miles of river. It is a mile deep and averages 10 miles across rim to rim. The North Rim is higher than the South by a thousand feet (8,000 and 7,000 respectively). The Colorado River has an average width of 300 feet, closing to only 76 at its narrowest point. But Grand Canyon is probably less well represented by statistics than most places. It has been termed one of the seven natural wonders of the world. No listing of depth, width, or area can convey what simply standing before it and taking in its wonders can afford.

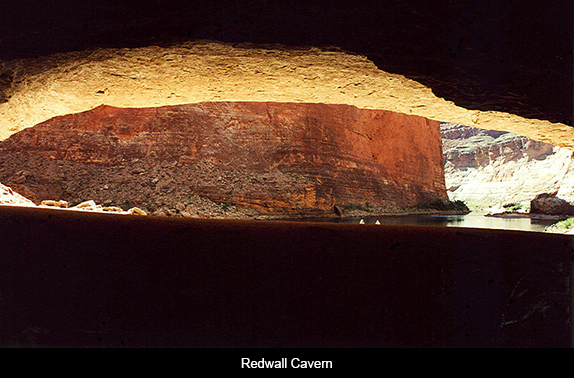

There is an astonishing difference between gazing at the canyon from its rim and going into it, even if you venture only a quarter mile or so down one of the well-tended trails. Walking even that short distance changes one’s perceptions. For one thing, the moment you enter the Canyon there are far fewer people experiencing it with you. You are more alone with those layers of rock, more in touch with their enfolding arms, more deeply touched by the Canyon’s magic. Even on top, if you walk away from the hub of tourist activity you will see a different Canyon. The free shuttle service along the West Rim drive is perfect for those who may want to walk a bit and then ride to a further destination or return to the village.

Another spot not to be missed, if you have time, is Desert Watch, the Mary Colter stone tower built on a promontory about 25 miles out along the East Rim Drive. This is a construction with no discernible purpose except that of allowing visitors to experience the Canyon in new ways. Stairs rise inside the circular building, allowing you to see a variety of vistas through small rectangular windows and go out onto terraces at various levels. The East Rim is particularly spectacular. Inside the tower, paintings by Fred Kabotie and others lend an added dimension.

But the magnificence of Grand Canyon resides in the chasm itself: 6 million years of sculpted Kaibab, Coconino, Mauve and Redwall limestone, Hermit and Bright Angel shale, schist and other sedimentary rock shot through with igneous folds, faults, overturns and intrusions. The panorama displays a palette of ever-changing light and shadow. Whether you are able to hike the Canyon’s intimate interior or only have time for a glimpse from the rim, there is nothing that can top this utterly unique place. Its vast power empowers you, even as it situates you as a speck in the natural world.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Grand Canyon”