New Mexico, late in acquiring statehood (1912) but ancient in its cultures and traditions, has attracted tens of thousands of residents originating somewhere else. The Spanish Conquest proved tragic to indigenous people here, who resisted, survived, and today contribute to life alongside more recent groups. Hispanics and Genízaros, Crypto-Jews and artists, writers and commune-dwellers of the 1970s, cutting edge scientists and architects, gurus and their followers: all these and more have imbued our state with its splendid diversity.

Along with these general groups, and others, some transplanted individuals stand out for the uniqueness of their contributions or histories: Billy the Kid, Gerónimo, D. H. Lawrence, Robert Oppenheimer, Edith Warner, Mabel Dodge Lujan, Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, Agnes Martin, John Lewis, Herb Goldman, Eliot Porter, Elaine de Kooning, Shirley MacLaine . . . the list is a very long one. Among these, perhaps none was more interesting, or took more from and gave more to, New Mexico than the painter Georgia O’Keeffe (1987-1986).

O’Keeffe’s presence permeates a part of the state to the extent that some of us call the area where she lived—the Chama Valley, encompassing Ghost Ranch and the village of Abiquiu—“the Georgia O’Keeffe country.” If you are familiar with her art and drive through this part of northern New Mexico, particular paintings will suddenly come to life around a bend in the road or in the spectacular near distance. The multicolor cliffs, Indian and Hispanic cultures, and objects such as animal skulls that inhabited her work remain unchanged from when they inspired her.

O’Keeffe was born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, migrated to the eastern part of the country, and entered the art world in the mecca that was New York City early in the twentieth century. She married the important photographer Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), who both promoted her work and curtailed her yearning to become the artist she was meant to be. Stieglitz was considerably older than O’Keeffe. Although their relationship was important to them both, she eventually broke away, coming to the American Southwest where her life and art became her own.

In 1929, O’Keeffe visited New Mexico for the first time, traveling by train to Santa Fe with her friend Rebecca Strand. Art patron Mabel Dodge Lujan soon moved both women to her community in Taos, and gave them studios. Strong women were important to O’Keeffe throughout her life, among them Strand, Lujan, and Maria Chabot. O’Keeffe lived for a while at the Lawrence Ranch, Ghost Ranch, and eventually built a permanent home in the tiny community of Abiquiu, high on the bluff above what was then a dirt road and is now Highway #85. The landscape of the Chama Valley intrigued and inspired her; she never tired of painting its mysteries. In 1929 she purchased and taught herself to drive a Model A Ford, in which she roamed every part of that landscape accessible to early automobile travel.

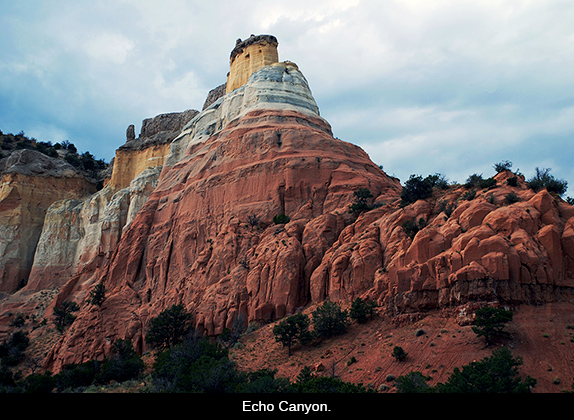

She often spoke of her relationship to northern New Mexico: the area around Ghost Ranch, a spot she called “The Black Place” (about 150 miles west of the Ranch), and the mesas surrounding the home she built at Abiquiu with the help of Chabot. Among her many expressions of identification with this land, in 1943 she explained: “[It’s] such a beautiful, untouched lonely feeling place, such a fine part of what I call the ‘faraway.’ It’s a place I have painted before . . . even now I must do it again.” And in 1977 she wrote: “The cliffs over there are almost painted for you—you think—until you try to paint them.”

Georgia O’Keeffe was indeed a loner. Her relationships with Stieglitz, Chabot, and others were important. Toward the end of her life she lived with Juan Hamilton, a young potter who was her companion, helpmeet, business manager and friend. The court battle after the painter’s death at 98, disputing what some called Hamilton’s “undue influence” on O’Keeffe, was finally settled, with the majority of her estate going to a foundation and his being allowed to keep her home at Ghost Ranch and a number of her paintings. Her work can be seen in major museums throughout the world, and in 1997, seven years after the artist’s death, The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum was opened in Santa Fe. It is located at 217 Johnson Street.

This private, non-profit museum was founded in 1995 by philanthropists Anne and John Marion, in order to preserve O’Keeffe’s artistic legacy and promote an understanding of her importance to the history of contemporary art. Some have called her the founder of Modernism, and the museum also has as one of its goals the study of American Modernism (a phenomenon that began at the end of the nineteenth century and continues to the present). The museum’s collection started with 140 paintings, watercolors, pastels and sculptures, but now holds more than 1,000, making it by far the largest repository of her work available to the public in a single institution.

Another serious O’Keeffe institution is the Research Center, housed in Bergere House at 135 Grant Street, also in Santa Fe. It sponsors research on American Modernism by awarding stipends through its competitive scholar program to historians in the fields of art, architecture, design, literature, music, and photography, as well as museum professionals. Early in 2006, the President of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and the Chairman of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation announced that their boards had signed a letter of intent, establishing the principles under which the Foundation would transfer all of its assets to the Museum. These assets included more than 800 O’Keeffe artworks and the house and studio in Abiquiu.

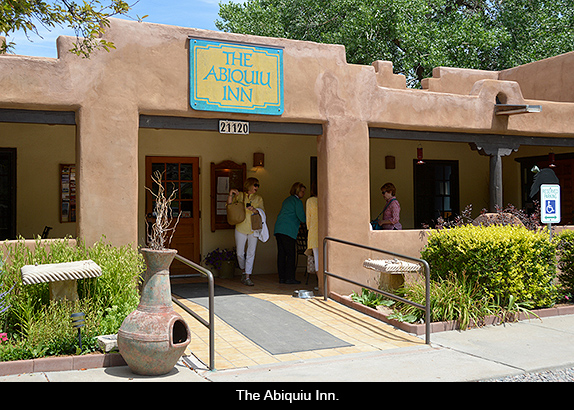

The Museum has tours of the Abiquiu house that are run out of its tour office on Highway #85 next door to the Abiquiu Inn and just across the highway from the road leading up to the village. These tours run from mid-March through November. They cost $35 to $65 per person, depending on the type of tour. The more expensive are led by the Historic Properties Director, who worked with the artist for over ten years, and provides “insights into her daily life.” Alternately, there is a Behind the Scenes Tour from June through September, on which guests are permitted to go “behind the Black Patio Door that inspired O’Keeffe to paint it many times and where she prepared her canvases.” For information and reservations, contact 505-685-4539 or visit www.okeeffemuseum.org.

If this sounds like a rather strange commercialization of O’Keeffe’s life and work, this writer believes it is. All famous people, of course, especially after their deaths, tend to spawn the range of consumer items—cups, notecards, posters, recipe books, and so forth—that enable the paying public to “have a piece of them” and make money in perpetuity for those who own the rights to such commercialization. This generally follows a scale, from beautifully printed reproductions to bogus objects having nothing to do with the values espoused by the person’s life or work. One must also look at where the money from such sales goes: into private hands or to an institution that keeps the art alive.

In the case of O’Keeffe, because the money from the tours is managed by a non-profit with the aim of preserving the artist’s legacy, I can’t complain. And the private companies that produce and sell O’Keeffe memorabilia generally do a decent job. In my opinion, though—and it is only my opinion—there is something strange about the tours of the Abiquiu house. After taking one, I felt I had been sold more hype than given meaningful insight into O’Keeffe’s extraordinary life and work.

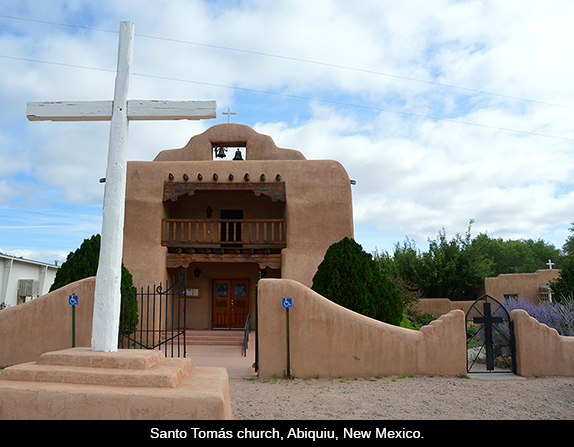

One can also drive up into the village of Abiquiu on one’s own. The village was founded in 1754, 22 years before US independence. On the small plaza, the church, which O’Keeffe supported generously, is well kept up. It is called Santo Tomás and is a typical example of the adobe churches that dot northern New Mexico. There are a few other buildings of moderate interest. But O’Keeffe’s home is secluded behind a wall and thick screen of old trees: no trespassing except by tour. Sunday through Thursday, in the mornings from 11 to noon and afternoons from 3 to 4, the Abiquiu Library conducts tours of the village at $15 per person (call 505-685-4884 for information and reservations). These, of course, do not include the artist’s house.

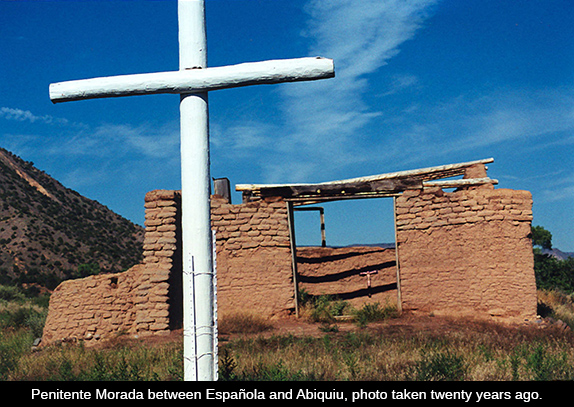

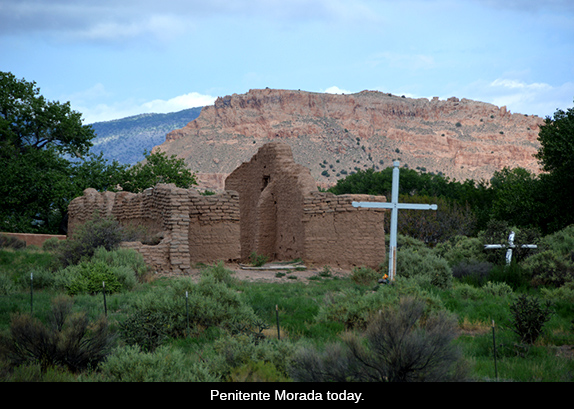

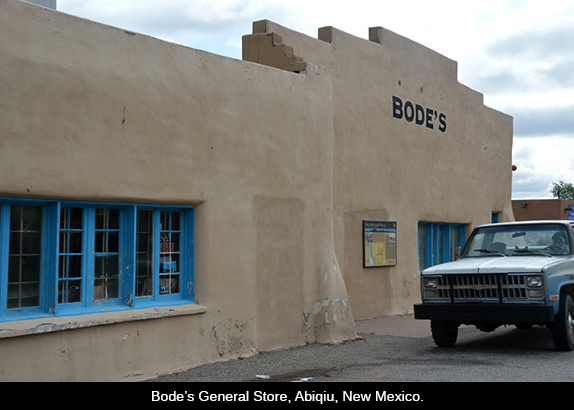

Quite apart from the commercialization—ordinary or extraordinary—you can also get a feel for what Georgia O’Keeffe loved so much about this area by exploring the Chama Valley on your own. Places of interest abound. Some were landmarks in her time and are memorialized in her work. Others have been established since. A very short list includes Christ in the Desert Monastery (where guests are welcome), the Dar al Islam Mosque and nearby White Place, Ghost Ranch, Echo Canyon (a National Park Service site), the Tierra Amarilla courthouse (site of the famous 1967 takeover), the village of Los Ojos with its inviting Tierra Wools Cooperative, the El Rito campus of Northern New Mexico University, the lovingly preserved ruin of a Penitente Morada between Española and Abiquiu, Bode’s general store, and the Abiquiu Reservoir. All are within an hour of each other.

A convenient and congenial place in the area to have lunch or spend the night is the Abiquiu Inn, across the highway from the road that leads up into the village. The Inn has 25 casitas situated among large Cottonwood trees. The food is delicious. The office for O’Keeffe’s home and studio tours and the Abiquiu Realty (if you’re interested in researching land opportunities in the area) are also on the premises, as are Galeria Arriba, hosting exhibitions of local artists, and a gift shop where clothing, crafts, books and some of the more tasteful of the artist’s memorabilia are sold. By official tour, or on your own, the Georgia O’Keeffe country is well worth seeing.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Georgia O’Keeffe Country”