Yucatán and Quintana Roo are the two states that make up the Yucatán peninsula in southern Mexico. Both have coastal expanses along the Gulf and beautiful beaches. Both are studded with ancient Maya ruins (many restored and available for visit, many more still hidden beneath the luxuriant semi-tropical landscape). Both have colonial cities, and small villages where life is traditional and moves slowly. Quintana Roo is best known for the Riviera Maya and Cancún’s string of resort hotels. Yucatán’s capital city is Mérida, with colonial buildings, a variety of old churches, and important contemporary museums.

We made Mérida our base in mid February 2015 for visits to a number of Maya sites, the ruins of great cities such as Chichén Itzá and Uxmal as well as several smaller but no less fascinating ruins. Here I will write about three of these: Kabah and Labná on the Ruta Puuc, and Dzibilohaltún, north of the city and so close it can be reached in ten minutes by car.

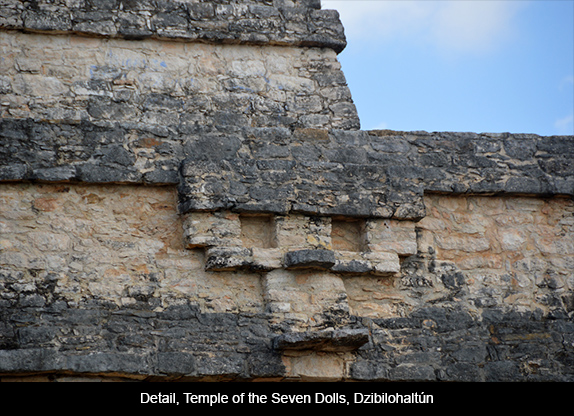

Dzibilohaltún, continuously occupied for thousands of years (although its population fluctuated through the centuries) is unusual, rarely featured in guidebooks, and we only discovered its existence because someone with whom we struck up a conversation at a restaurant told us about it. Its relative proximity to the coast may indicate it was on a trade route. Among its special features are a structure called Temple of the Seven Dolls, so named because seven small effigies were found when it was being cleaned and restored. In form this temple resembles some I have seen in Southeast Asia as much as it does others of the Maya world. A long sacbe, or built up pathway, leads from this building to the other end of the site, where the ruin of a Christian church shares space with several other Maya-era constructions. The syncretism between the two cultures is startling.

At this end there is also a large cenote or natural water hole called Xlakah. Price of admission to Dzibilohaltún includes the use of a changing room and a swim in the cenote, as well as a visit to a museum with many beautiful items on display. A garden just before you reach the museum holds an interesting range of larger pieces: stelae and full body sculptures. We shared Dzibilohaltún with less than a dozen other visitors, and our several hours there were well worth the trip.

Two hours by car directly south from Mérida, is the Ruta Puuc, a string of ruins smaller and much less visited than Uxmal but closely related to the larger city. Think Chaco and its outliers. Each of these ancient sites is connected to the metropolis by roads, many of which (unlike the Chaco roads) are still in use. At least half a dozen of these ruins are open to the public, at varying admission prices and with a range of amenities. All have sanitary facilities, a few offer the service of a guide, almost all attract many fewer visitors than their larger counterparts, and it isn’t unusual to have the place practically to oneself. Several hours may be happily spent exploring each.

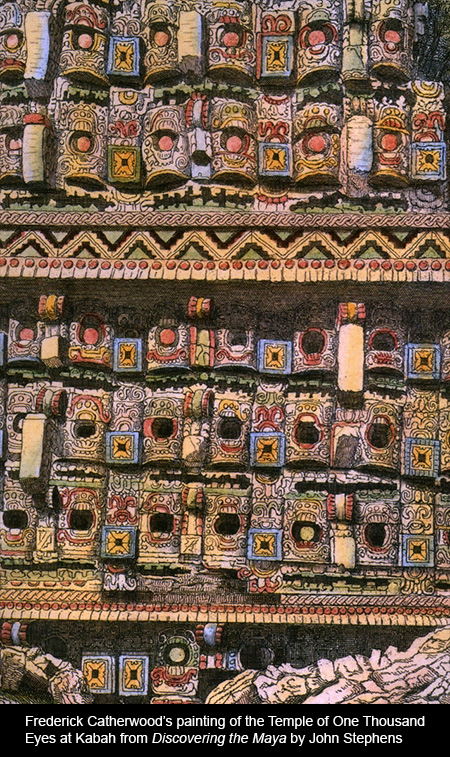

Off the main highways, narrow one-lane roads cut through thick jungle growth, sometimes coming together to form canopies of green. The ruins appear as if out of nowhere, their impressive pyramids and temples visible from the road. We started at Kabah, famous for its Temple of One Thousand Eyes. What is only visible today in carved stone was still brightly colored when Frederick Catherwood painted it in the mid-1840s.

These smaller ruins are full of surprises. And each is an entirely different experience. Kabah, with its many large and ornate buildings, had only a ticket seller, a woman minding the rest room, and a lone guide on duty when we arrived. The guide, Marco, turned out to be an expert wood carver as well; he displayed his statues and plaques on a small table near the entrance. All had Maya motifs. Some were quite beautiful.

We opted not to use a guide but to wander at will. A bank of steep steps leads from the well-tended grounds to an upper level where temples and courtyards abound. This was a place to sit in the shade of a rare palm and contemplate our surroundings. This whole area was inhabited by the mid-3rd century BC. Most of the architecture now visible was built between the 7th and 11th centuries AD. A sculpted date on a doorjamb in one of Kabah’s buildings gives the date as 879, probably at the height of the city’s glory. Another inscribed date is one of the most recently carved in the Maya Classic style, a little over one hundred years later in 987. Kabah was abandoned, or at least no new ceremonial architecture was built, several centuries before the arrival of the Spaniards.

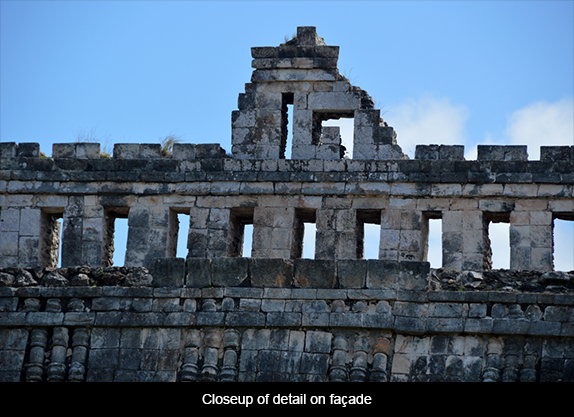

The most famous structure at Kabah is the Palace of the Masks. Its sides are covered with hundreds of stone masks of the long-nosed rain god Chaac. This structure is alternately known as the Codz Poop, meaning “rolled matting,” because of the pattern of stone mosaics on its façade. This massive repetition of a single set of elements is unusual in Maya art, and here it is used to unique effect.

We lingered at Kobah, exploring out of the way details and pondering what life may have been like for those who lived here when it was a bustling city. We were reluctant to move on.

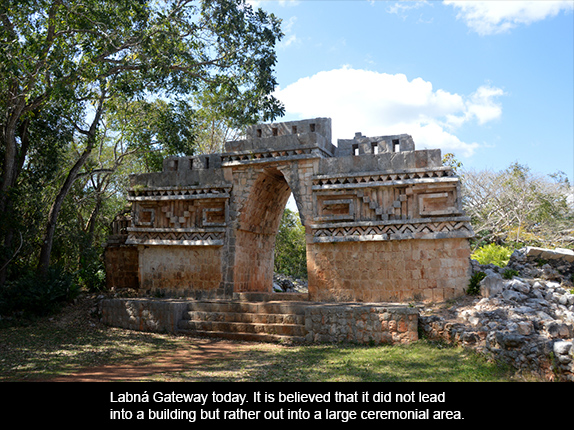

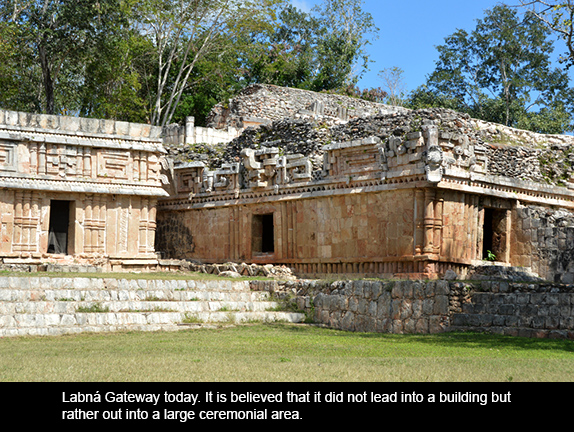

But move on we did, to Labná, another of the ruins along the Ruta Puuc. Labná seemed emptier and lonelier, if possible, than Kabah; there may have been one or two others on the grounds while we were there. This site was built in the Late and Terminal Classic eras. A date corresponding to 862 AD is inscribed somewhere in the palace. The first written report of Labná was by John Stephens, from his 1842 visit with Frederick Catherwood. Stephens wrote:

There is an arched gateway remarkable for its beauty of proportions and grace of ornament. […] On the right, running off at an angle of thirty degrees, is a long building much fallen. […] On the left it forms an angle with another building, and on the return of the wall there is a doorway […] of good proportions, and more richly ornamented than any other portion of the structure. The effect of the whole combination was curious and striking, and, familiar as we were with ruins, the first view, with the great wall towering in front, created an impression that is not easily described. Passing through the gateway we entered a thick forest, growing so close upon the building that we were unable to make out even its shape; but, on clearing away the trees, we discovered that this had been the principal front […]

Indeed the Gateway leads nowhere. And it is still not easily described.

Labná contains several surprising structures, one of which is a tall pyramid on two levels. The upper level is a well-preserved temple with a tall and ornate roof comb reminiscent of those one sees at Tikal, in Guatemala. The bottom half of the pyramid is covered in displaced rocks, rather like a debris field on a mountainside. Clearly, smaller sites such as these have been renovated or cleaned just to the point of preservation and providing safety but not reconstructed in any major way. This gives them an evocative quality. One’s imagination is invited to complete the picture.

Labná, like the other sites, still had its sacbe, on which we walked from one part to another. Old growth trees were everywhere.

Although Uxmal and Chichén Itzá are considered the jewels of Yucatán, not taking the time to visit the smaller sites would be a mistake. Only by strolling through several does one get some idea of the rich variety created by hundreds of Maya architects. Just as in our contemporary cultures, the visions were different and results complex.

March 13, 2015