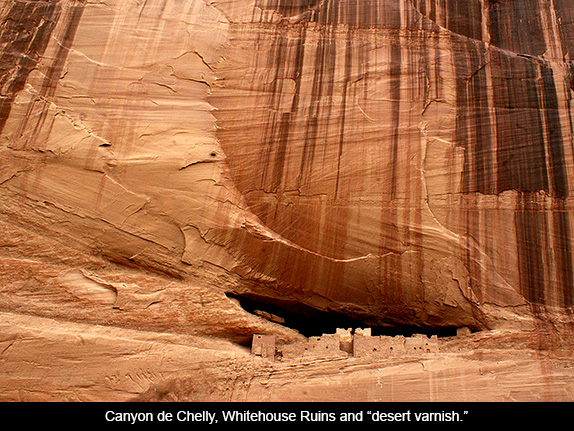

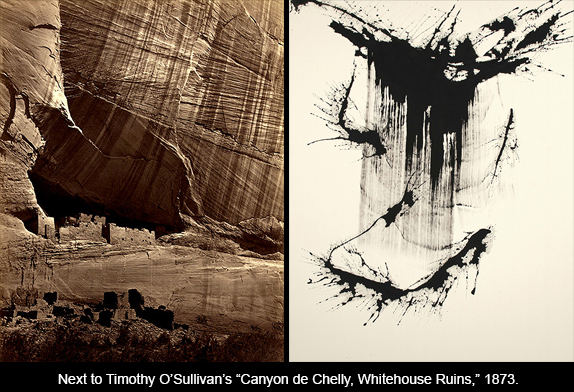

Camping at Canyon de Chelly sometime in the 1970s, Zachariah Rieke kept looking up at the so-called “desert varnish” on the stone cliffs—those long vertical mineral stains deposited by water runoff. For thousands of years, the desert’s most coveted heaven-sent substance would make its brief appearance in the canyon, pour over the cliffs, and then depart. Yet it left behind an enduring image of itself. It occurred to him that the massive canyon walls had been streaked with nature’s painting.

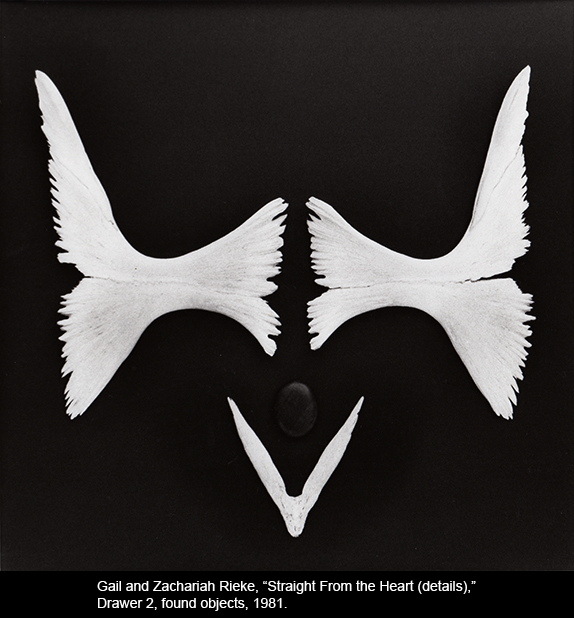

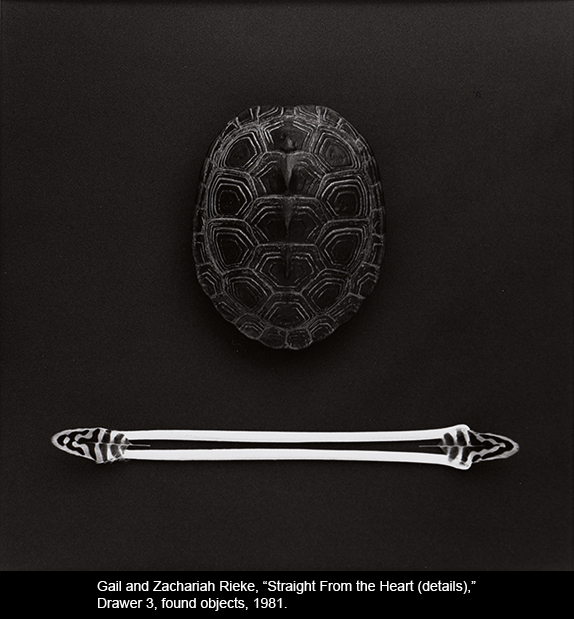

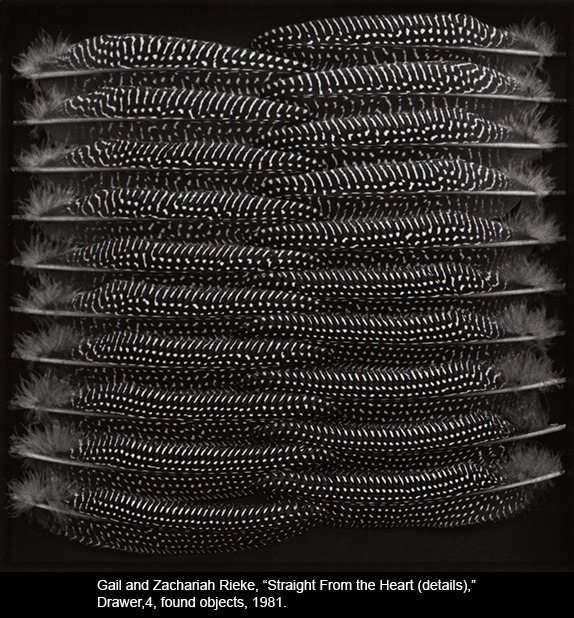

Together with his wife Gail, he has had a longstanding interest in nature as designer. Both are keen observers and collectors of nature’s patterns and textures, and the Riekes often collaborated on making art. They gathered together such things as folded and bundled palm leaves and paper hornets’ nests, spotted guinea feathers, tiger-striped nautilus shells, bones and porcupine quills, moth wings and shed snake skins, bits of rusted metal or weathered wood, and they arranged these finds into boxed collages and drawers. It was a process of natural selection, based in the discovery of visual harmonies and analogues. The resulting artworks meditated the beauty of forms that have been shaped by natural processes of growth and evolution and by the ineluctable effects of time.

Born in 1943 and raised on a Kansas farm, Zack Rieke spent his childhood in close contact with nature. Life on the rugged prairie immersed him in the changing seasons and provided an intimacy with the ecology of all living things. Yet the land of his childhood was littered with evidence of the human struggle with nature. Broken down parts of wrecked and weathered machinery, ruins of abandoned windmills and barns, these were constant reminders of hapless generations of farmers and their alienated contention with the elements. In later years, the textures of time and weather would become a recurring element in his art. For a while, he let the dark history of human frustration in conflict with nature emerge in painterly outbursts of destructive energy, and in the incorporation of various aging collage elements, from faded farm ledgers and bullet-riddled road signs, to rusted scraps of battered metal, sun-bleached and distressed wood, and even ashes. Eventually, however, his art would entail a search for reconciliation. It has become a means for reconfirming oneness with nature, while acknowledging the relentless passage of time.

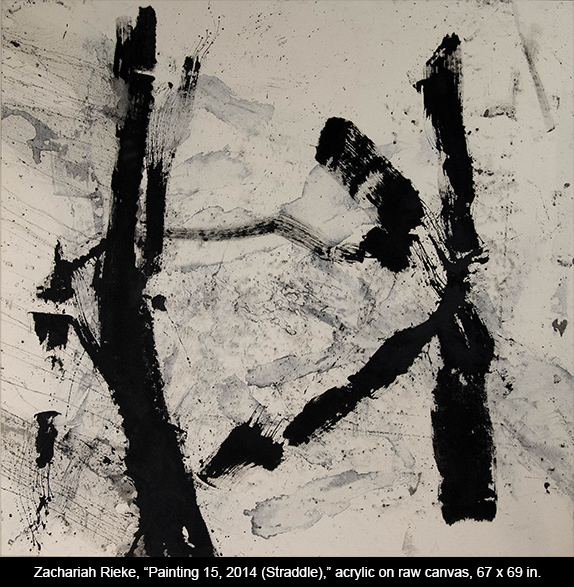

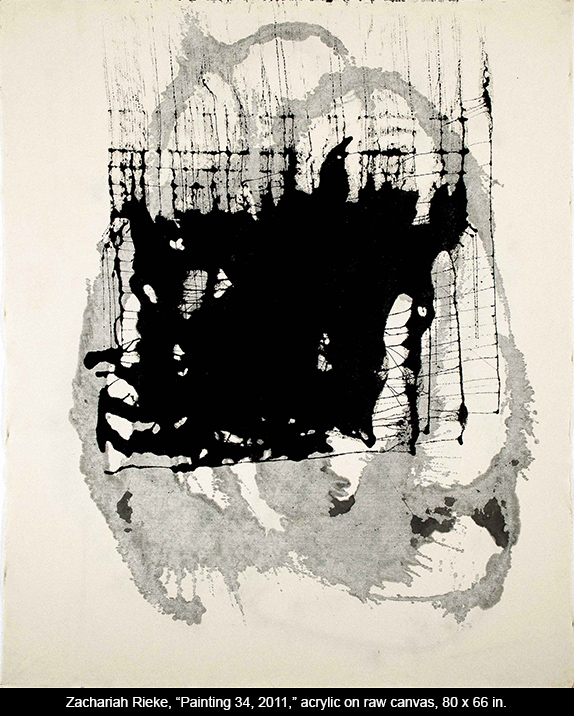

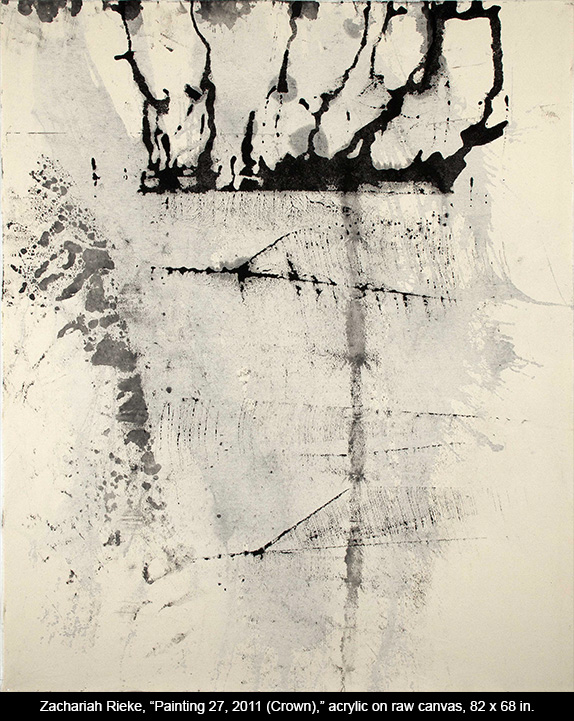

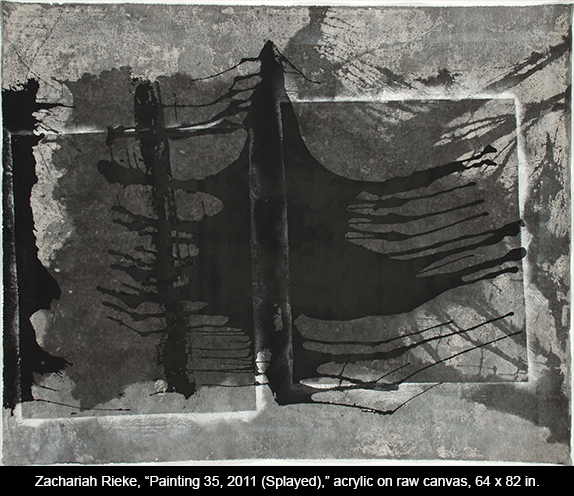

His early training as an artist came from teachers steeped in Abstract Expressionism, and over the years he has retained many of the tenets associated with “Action Painting.” Like Jackson Pollock, Rieke’s preferred method is to work with unstretched canvas, laid either on the floor of his studio or outdoors on the gravel of his backyard garden. Pigment is applied in various ways and in a variety of consistencies—from dry powder to thick paste to thinned watery washes. It might be thrown or poured onto the surface, or brushed on with a broom or mop. It can sometimes even be printed onto the canvas by offsetting from some other pigmented surface. In some recent paintings, he created a delicate veil-like effect by sweeping the surface with the fringed edge of another paint-soaked canvas. Rieke tends to work both sides of the canvas fabric, frequently developing a finished piece from stains that have seeped through from behind. His process promotes spontaneity and random evolution, responding to the materials and following their course as they reveal their own natural tendencies.

A deep connection with Asian aesthetics is evident in Rieke’s recent work, in both its process and results. Attracted long ago to the expressive energy and economy of Japanese brush painting and its Chinese antecedents, Rieke also felt an affinity with the philosophical bases of these traditions. The wisdom of Zen Buddhism with its roots in Chinese Taoist principles informs his working process perhaps even more profoundly than his background in Abstract Expressionism.

As Alan Watts points out (in The Way of Zen, p. 174), “The arts of Zen are not merely or primarily representational. Even in painting, the artwork is considered not only as representing nature but as being itself a work of nature. For the very technique involves the art of artlessness, or the ‘controlled accident,’ so that paintings are formed as naturally as the rocks and grasses which they depict.”

Zen painting originated in the more ancient brush art of Chinese painting and calligraphy, whose principles were formulated in the Six Canons of Painting, set down around 500 CE. These called for an effortless execution: the action of painting should seem to take place of its own accord, like a natural process.

Indeed, as the first canon states: Ch’i yün sheng tung, which roughly translates as “Spirit consonance renders life movement.” Ch’i means “spirit;” but, like our word “spirit,” its original meaning is “breath.” And since it implies “the breath of life,” like our word “spirit” it is associated with the “soul,” the animating factor, which is “taken into” the body and activates the mind. Its use here is meant to convey more than the simple need to harmonize your breathing. It refers to the origin of life (and of the universe as a whole) in the mysterious concept of the Tao—which in ancient thought is not a thing or event (or even a “Big Bang,” although it is said to be “the mother of all things”). Instead, the Tao is described as a kind of “path” of coming and going, more or less like the automatic action of breathing itself. Hence the canon states that, in preparing to paint, if you bring your breath/spirit (ch’i) into a state of harmony (yün) with itself and the world, letting everything flow without the intervention of self-consciousness or ego, then the result will contain the living quality of a natural occurrence. It will convey nature’s impulsive growth and spontaneity (sheng tung), as if nature itself had rendered the painting.

The beauty of the natural “brushstrokes” at Canyon de Chelly caught Zack’s attention. But it was the spontaneity of their natural occurrence that haunted him, and which over the years would influence his own artistic process. At the center of his process is a desire to align his painterly work with nature in its manner of operation, and to open himself to the full dimensions of that commitment.

It is said that “the Tao that can be spoken is not the true Tao.” Nevertheless, we might say that the Tao is the source or essence of all movement or action; and that throughout the cosmos, it is always and everywhere ongoing: it is simply “happening.” If Lao Tzu described the Tao as a “path” or a “way,” it is less like a path to or from a destination and more like an ongoing “way of doing”—as when people say, “It’s our way of doing things”—or, perhaps, like the “way of the open road.” It is basically the principle of activity; more a verb than a noun. Like our sense of hearing, it is ongoing—happening—whether or not anything is presently making a sound or whether we are actually listening. So, together with his vision of the spontaneous occurrence of imagery in the natural world, Zack Rieke acknowledged the simple truth behind the Taoist “way” of the world: it just happens. As stated in a Zen poem about geese passing over a lake: “The wild geese do not intend to cast their reflection; / The water has no mind to receive their image.”

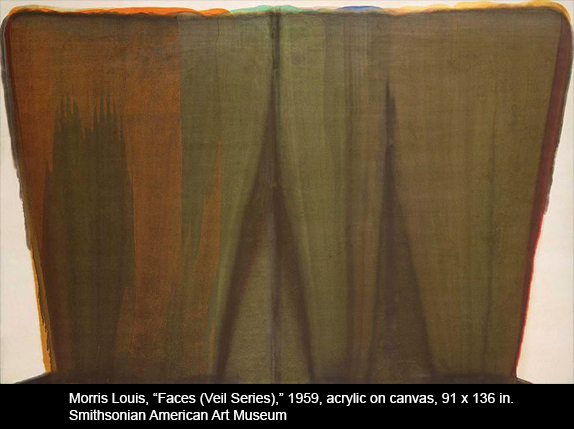

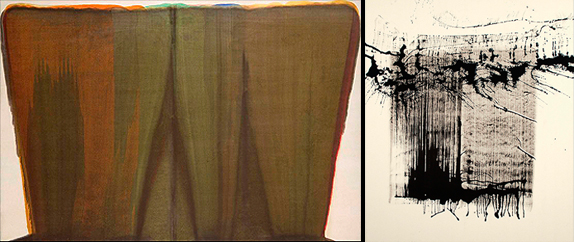

Only someone with Rieke’s firm experience of Abstract Expressionism and knowledge of Asian calligraphic brush painting traditions would see those canyon streaks of water runoff as “brushstrokes.” And only someone with a strong background in American Modernist painting would recognize, too, how the “desert varnish” had transformed the canyon wall into a natural equivalent of one of the monumental “Veil” paintings made by Morris Louis in the 1960s. Louis’s works, with their broad sweeping surfaces and their poured stains, resulted from a deliberate attempt on his part to “naturalize” his painting process. Following the example of Jackson Pollock, Louis sought to free his paintings from the artist’s hand. Using a largely automatic process involving successive pours of thinned pigment onto unstretched canvas, his aim was to allow the painting to more or less realize itself. He wanted to have the painting evolve and become an autonomous world unto itself, a world as independent and self-contained—as autonomous—as the world of nature itself.

And so it was that when Zack Rieke was looking at “nature’s painting” in Canyon de Chelly, he was also standing at a crossroads of East and West—between two great traditions for achieving naturalness in painting. On one side was Chinese brush painting with its Taoist philosophy. On the other, however, was not the traditional European version of naturalistic representation, but American Abstract Expressionism and the natural automatism that resulted from its Modernist philosophy of critical self-definition, truth to materials, and the desire for complete immediacy. Nothing would be represented that was not there; and the materials would be allowed to simply be themselves and run their own course.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Zack Rieke’s new work is its spontaneous freedom and release. This comes after a lifelong engagement with materiality. During his hardscrabble childhood as the son of a sharecropper, he had to create his own makeshift entertainment, utilizing whatever scraps and broken implements he found on the farm and combining these with sticks and stones, clay and mud. Consequently, when he encountered Robert Rauschenberg’s “combine paintings” as an art student in the early 1960s, their juxtaposition of physical materials and painterly action seemed a perfectly familiar way of making art. He was already sensitive to the eloquence of the concrete physicality of materials, and on the farm he had witnessed their testimony to time and endurance, their ongoing alteration by the ever-present forces of nature and weather.

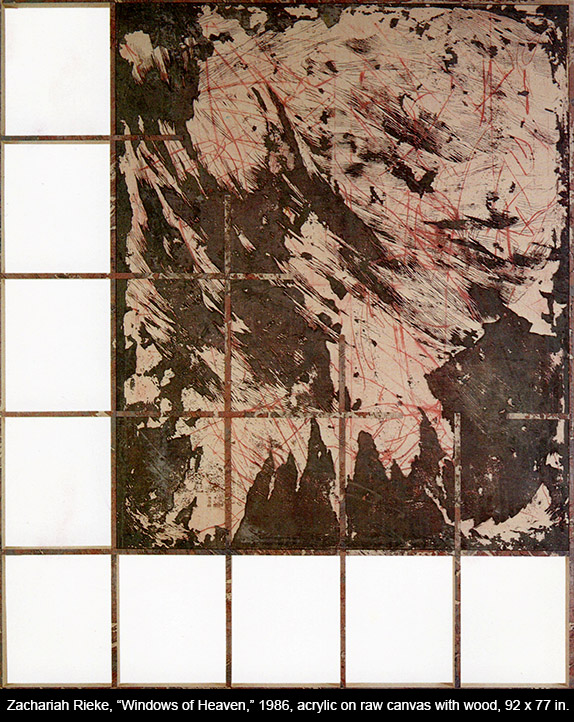

In the 1970s, when I first met the Riekes, they were living in the country near Edgewood. At the time Zack was doing most of his painting outdoors, on the ground. Subsequently, in 1980, they moved to Santa Fe for the sake of their growing family and the children’s schooling. There he continued to work outside and in a converted garage studio. His work was characterized by the use of materials that had been “acted upon.” These included not only distressed collage elements of such found materials as rusted metal and desiccated wood, but also the use of aging techniques, such as leaving the canvas outdoors for long periods of time, weathering and roughing the surfaces and then inflicting the damaged gesso with further scratches and scarring.

He also utilized methods of pouring and spattering liquid pigments in earth colors, allowing them to dry slightly under the sun until they had curdled along their edges, and then washing them out with a hose so that they left only a skeletal remnant of their presence and of their violent application. The effect was like that of the various mineralizing processes of nature—a fossilized leaf embedded in stone, the layering and erosion of sedimentary rocks, or the fused substances of igneous geological formations. While most of these techniques were passive, allowing nature to take its course, some of them were violent—including the splintering of plywood that had been glued to the canvas surface and then ripped away, or the tearing apart of two heavily pigmented canvas surfaces that had been laminated together, a process he called “flaying.” In addition to the achievement of unexpected textures, these procedures showed that there was nothing sentimental in Rieke’s appreciation for the beauty inherent in nature’s formative processes.

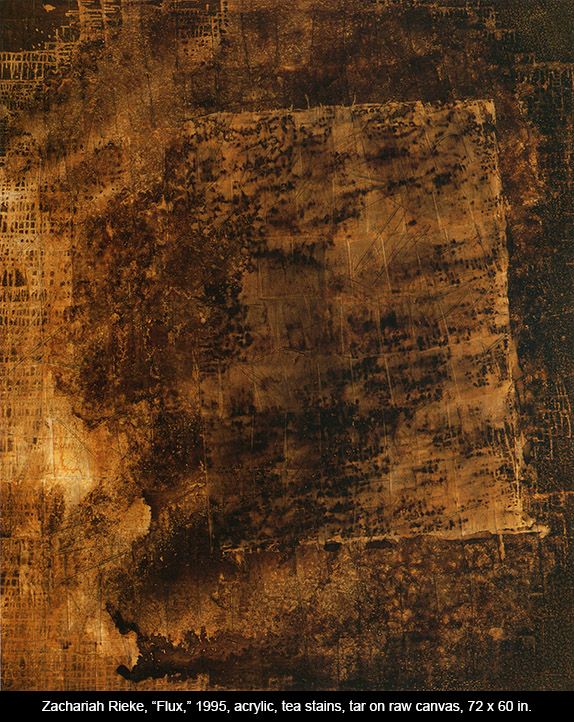

In the 1990s his interest in Japanese aesthetics deepened, partly through Gail’s involvement in her work with the sensibility known as wabi-sabi (an appreciation for the effects of time and loss and a mood of lonely dejection). His engagement with materials reflected concerns similar to the induced accidents and sophisticated humility of raku pottery firing. Indeed, fire sometimes entered into his process. After staining a raw canvas with tea bags arranged in a grid pattern, he then applied tar to the reverse side; when it dried, he poured lighter fluid over it and set it on fire. The tar melted and seeped through, interacting with the tea stains in unpredictable ways and creating a richly complex surface. He had been using dirt and sand mixed with his pigments and soon he was also including ashes—both for the gritty texture of their color and for their evocation of transience. By the early 2000s he was combining the ash-laden pigments with watery washes that dispersed them over the surface in a series of large-scale paintings called “Smoke Rings.” Another group with a similarly circular or spiraling action was called “Twister,” invoking the forces of a Kansas tornado. Sometimes the paintings’ imagery included empty rectangular frames, architectural elements drawn with thick black strokes that resemble charred embers.

In 2005, Rieke began experimenting with the circular Zen gesture known as ensō. A figure of immediate and spontaneous bodying forth, the ensō traditionally marks a moment of sudden spiritual revelation. Aware of the Japanese practice of large-scale calligraphy called hitsuzendo, and its Zen discipline of placing oneself fully inside the moment with “nothing in mind,” Rieke rolled out a piece of canvas onto the gravel in his backyard. Standing in the center of the canvas, he took up a long-handled broom, plunged it into gritty black gesso, and swept a sudden gesture around himself. Full of force and futility, like the spinning spatter of a mired wheel, the gesture traced his body’s movement and recorded a stuttering imprint of the underlying gravel. The action produced a large bold statement under the sun, a meeting point of Zen and Ecclesiastes. Nothing new, really, but a fresh declaration poised between emergence and dispersal. Brought forth out of nothingness, the sweeping “zero” of the Zen ensō is a calligraphic circle meaning “no form,” where the artist traced himself as the absent center.

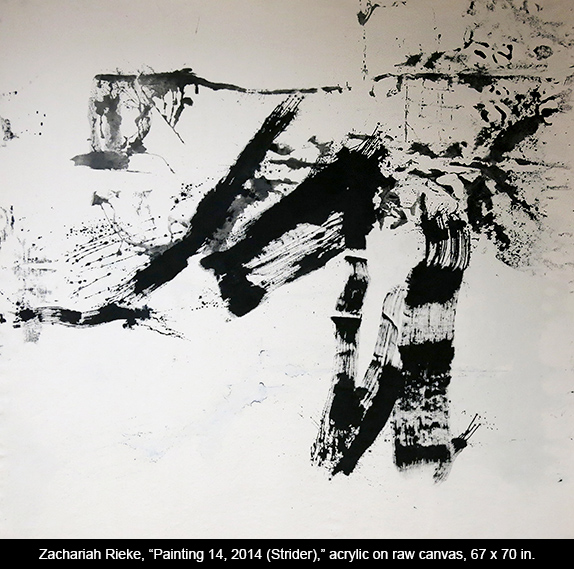

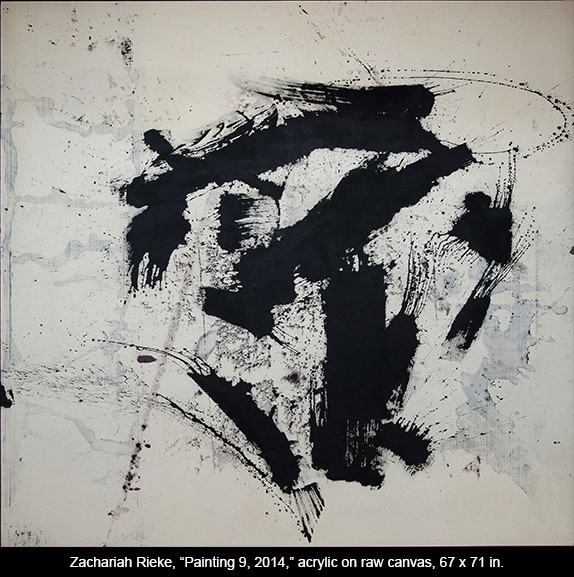

The ensō would provide the prototype for the kind of singular, bold configuration that characterizes Rieke’s newer work. After an intervening period, 2006 – 2009, when he produced a series of very fluid and lyrical field paintings using high-key colors, Rieke returned to basic black in 2010. Large in scale, the new paintings of 2010 seemed to reproduce aspects of a primordial earth in formation, figured with dark and dripping chthonic masses, both generative and destructive, arbiters of birth and decay. There were also smaller paintings with more lyrical black markings suggestive of floral sprays or floating branches.

Rieke’s newer paintings are again reminiscent of Japanese calligraphic brush paintings, especially the “flung ink” style known as haboku. Sesshu (1421 – 1506), the first great master of the haboku style, was said to have used “fistfuls of straw” to achieve his effects, and Rieke’s large paintings from 2011 through 2014 are equally remarkable for the variety of means he utilizes to move paint around. With amazing versatility, he is able to strategically fling black gesso at just the right liquidity for breathtaking effects of spontaneity, energy, and unbridled expression. Explosive spatters and long runny streaks of thrown pigment seem to have painted themselves, and yet they arrive with unerring placement. How, you wonder, does he control the beads and runs of paint? How did he achieve the intricately woven network of dripping parallel lines that sometimes emerge?

Most of the recent works of 2014 feature an isolated, centralized configuration, much like a single brushed character in Asian calligraphy, the legacy of the ensō. In an ongoing dialogue of negative and positive in the works of 2012 - 13, Rieke sometimes also used an opaque white paint as a ragged overlay or blank erasure. Occasionally the chalky white was allowed to thin out and cloud the surface; sometimes it soaked in to form a matte ground, a dull gray undercoat like cement or limestone. Shadowlike show-through stains from the reverse side of the canvas would sometimes further embed the centralized configuration on these canvases, and a scruffy texture lent a sense of age and rugged endurance. Occasionally Rieke worked around rectangular masks that were laid onto the surface; and when these were lifted away, they left a hollow frame in their place—like an empty icon, or the memory of an abandoned order, washed away by the retreating wave of time.

Although painstakingly achieved, Rieke’s painterly canvases seem to have been produced by independent acts of nature and marked by the weathering of time. Like the Tao, like breathing, these paintings sustain an intimate integration of infusion and expiration, of both emergence and loss.

Zachariah Rieke is represented in Santa Fe by Wade Wilson Fine Art, 217 W. Water Street. During the month of August, the Riekes have a tradition of holding an open studio in their home at 416 Alta Vista Street, where Zack’s paintings may be viewed by appointment: 505-988-5229 or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address).

Responses to “Zachariah Rieke: The Tao of Painting”