This is the second and final column about a Yucatán journey. Read Part 1 here.

We traveled around Yucatán exclusively by public bus, which does have the advantage of giving you lots of idle time to study the people and countryside. Everybody has their own opinions on when and where the buses run, so you have to be resigned to long waits and occasional dead ends. Even though the distances in Yucatán are modest by U.S. standards, it takes a day or two to get just about anywhere by bus.

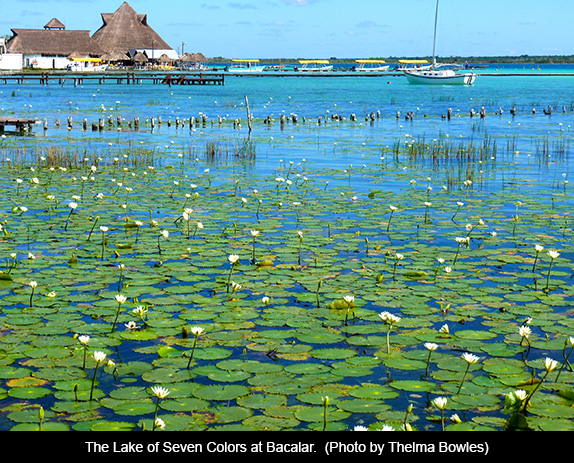

Such was the case with Bacalar, about 150 miles south of Tulum and perhaps the best surprise of our trip. The village is a charm. It is filled with parks. The streets are immaculate. The food and hotels are both good and cheap. A beautifully rehabilitated 200-year-old Spanish fort with an excellent historical museum overlooks the town. There are lots of well-maintained public beaches.

The beaches front on a vast fresh-water lagoon which is locally called the Lake of Seven Colors. The lake is technically a lagoon because of a narrow passage dumping its fresh water into the sea. The lagoon is every bit as spectacular in color and clarity as the sea itself. We left Bacalar after three days but could have stayed on and on and on.

An even more remote village, however, turned out to be a disappointment. It took us two days to get by bus from Bacalar to Xcalak, a village that our guide book (“Moon,” which was the only recent guide we found that was entirely devoted to Yucatán) described as “heaven.”

To get there we stopped overnight in the curious small town Mahahual. It is really two towns, existing in the same location at different times. When giant cruise ships disgorge their thousands of passengers (more people than live in all of southern Quintana Roo), locals open up their seaside stands and restaurants and jet ski and dive operations and start pestering passersby to buy their wares and services. Then in mid-afternoon the cruise ships leave and the stalls close and the streets empty. What you find then is the peaceful fishing village that once was all that existed here. During these quiet times, it is a pleasant town to stroll through with nice beaches and delicious street food.

After a night in Mahahual, we continued on another bus to the village of Xcalak, the end of the road and a town just 90 minutes by boat across a bay to the islands of Belize. There are two roads to Xcalak. The one we went there on was a new, straight, well paved highway that passes through endless jungle with nothing to see. The other road, the one we returned on, was the old one, still deeply rutted and potholed from being torn up by the 2007 hurricane, with views of the sea and occasional tourist lodges and fishermen’s huts.

The problem with Xcalak is that it is, if not dead, at least dying. Most of the small inns and restaurants were closed. Most of the private land and houses were for sale. The 2007 hurricane devastated the area, destroyed much of the mangrove forest protecting the coast, severely damaged the nearby reef and drove away most of the residents and nearly all the tourists. What remains today is only a shadow of what it once was. It is still a pleasant place to stroll around, in about the same way that an old cemetery is, but after one night we decided we had had enough of this particular pleasure.

Although some people from elsewhere in Mexico have been attracted to the new jobs in the resorts, the great majority of those living in the three states of the Yucatán Peninsula are still Maya. They are quite different from the mestizos that predominate in Mexico. They look different, shorter, darker, with more prominent noses, thicker waists and wider shoulders. The traditional Mayan dress, still seen from time to time, is a pure white for both men and women with brightly colored fringe decorations.

While the traditional Maya dress is less in evidence than on my first trip to Yucatán in 1960, the traditional sense of courtesy and honor has not receded. They Maya act in different ways from most Mexicans. They are more modest, utterly lacking in the swagger and machismo of many mestizos. They also lack the aggressiveness and pushiness often seen elsewhere in Mexico. When asking you to buy a basket or a tour or a taco, they ask once, politely, and if you decline, turn their attention elsewhere. And the level of honesty is phenomenal. Not only did we never fear theft, when on a couple of occasions a small amount of cash fell out of my pocket, a Maya bent down to retrieve it for me. They respond with friendliness when you want to talk, and retreat into silence when you don’t.

Our last night in Yucatán, we returned to Turquesa, took a final swim in the calm, nearly empty sea and walked miles along the world’s most beautiful beach.

Returning to our tent, we discovered something we had first seen in Sian Ka’an: two similar trees, a brown trunk with a fatally poisonous sap and a red trunk carrying the antidote to that poison. They were growing next to each other just outside our tent. One of them bore the sign, “Danger, Do Not Touch.” One of the piquancies of Quintanta Roo is that antidote and poison, safety and danger, heaven and despair are seldom far apart.

At 3:30 a.m. an efficient company called Holtelhoppa picked us up from Turquesa and delivered us directly to the airport terminal outside Cancún, enabling us to avoid entirely the overblown, crowded, Americanized high-rise resort city that, we felt, was the antithesis of everything that we had found, and loved, in the wonderful place called Quintana Roo.

Responses to “Yucatán Journey, Part II: Where poison and antidote are seldom far apart”