Refugees seeking safety from political or economic violence have been streaming across our southern border for decades. Rapacious politicians often refer to them as “illegals,” as if human beings can be anything but legal and deserving of opportunity (can we really think of a newborn as illegal?). These politicians’ campaigns dismiss the tearing apart of families and use the plight of their vulnerable children as the proverbial political football.

Living close to our southern border puts us in touch with this tragic migration and all its human and political ramifications. Grassroots efforts at aiding these victims of violence, arrogance and greed, and the socially conscious art that often emerges from their predicament, give us the opportunity to consider the human stories behind the distorted reports in our corporate news media.

The Mexican/US border is certainly not the only site of such suffering. As I began writing this piece, I received a letter from a friend in Germany. She described the “tens of thousands of refugees fleeing war and hunger in Africa, Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan,” her country’s attempts to reject them by force, and the organizing aimed at guaranteeing their rights and mitigating their suffering.

Even as we witness thousands succumbing to heat and thirst while trying to cross an inhospitable desert in our part of the world, my German friend speaks of the thousands each year who die when their overloaded boats capsize and go down in the Mediterranean. Death by heat or water is nothing less than death by indifference and political cruelty. In this 21st century, forced migration has reached unprecedented global levels.

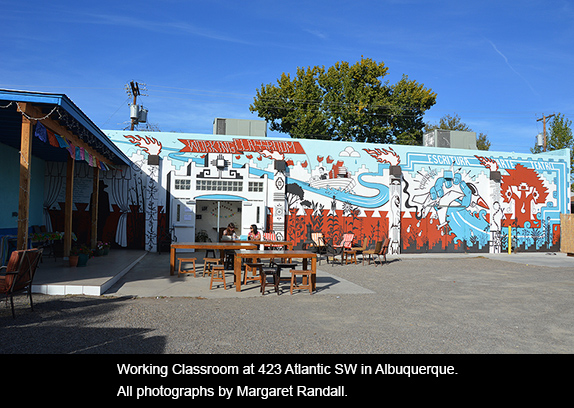

For almost as long as our own southern border has been a site of violence and human tragedy, Albuquerque’s Working Classroom has been offering professional training in English and Spanish to beginning, intermediate and experienced actors and artists from age 11 up. Many of these young people have experienced injustice or upheaval in their own lives. Through artistic expression in a variety of genres, the organization has raised consciousness about this and other social problems, empowering young people to use creativity to effect change—in themselves and others.

The organization knows it is not enough to have good intentions or decent politics, sadly the driving forces of too many well-meaning groups. Only through imbuing social change with real professionalism can it prepare its aspiring actors to “be the next Rosie Perez or Denzel Washington” (as its literature proclaims). And even those acting students who may not want to be another Perez or Washington gain experience that will help them succeed in whatever area they decide to explore.

Respect for diversity, bilingual expression, breaking down contrived barriers, and experimenting with new ways of speaking truth to power are necessary aspects of this work. Creativity is its vehicle.

Working Classroom offers scholarships to new and returning students. It holds workshops in digital storytelling, improvisation, theater of the oppressed, props and costumes, papier-maché, the confection of skeletons and other figures for the city’s annual Day of the Dead parade and other celebrations, public art and community planning, printmaking, piñatas, basic fighting techniques and stunt choreography for the stage, among much else. The organization is funded at the national, state and local levels, as well as by individual donors, enabling many students to pay only $10 to take a class.

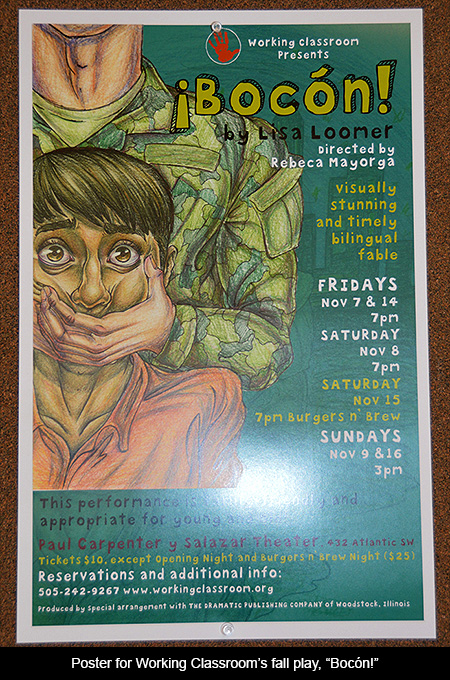

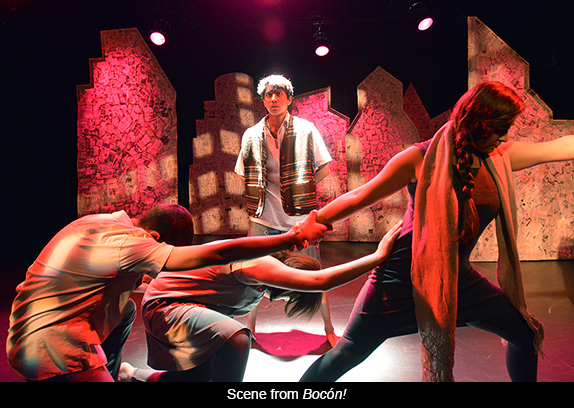

Bocón! is Working Classroom’s fall 2014 play, described on its poster as a “visually stunning and timely bilingual fable.” It was written by Lisa Loomer in 1986, and tragically is as on-topic today as it was back then. Rebeca Mayorga, who directed the inaugural performance, came back to direct this one, and the stellar cast is made up of Joel Garcia, Juliana Gorena, Jess Liesveld Roberto Morales, Michelle Perez and Sonya Tijerina. The behind the scenes designers and production crew showed themselves to be as innovative and talented as the writer, director, and actors: a simple but effective stage set and well-managed lighting are imaginative and work to enhance the whole.

In her Director’s Note, Mayorga writes:

What do we do with all these undocumented children? This is what we hear from the media, but a more meaningful question is, why are these children fleeing their homes? Bocón! explores some of the answers.

It is alarming that this play, written almost three decades ago, about a 12 year old boy who flees the violence and poverty of his Central American home, is just as relevant today as it was then. As the number of these young immigrants grows in huge proportions, it is our responsibility as theater artists to share their story in a compassionate, imaginative and accessible way.

In this conceptual production I attempted to give a face to the many children who brave countless dangers to get to a land where they believe they will be safe.

As a Working Classroom alumna it is very rewarding to be returning to direct the new generation of Working Classroom artists. The young actors’ willingness to research and tackle such profound issues is inspiring, and I look forward to seeing them grow as they continue to develop their craft and find their own voice in the world.

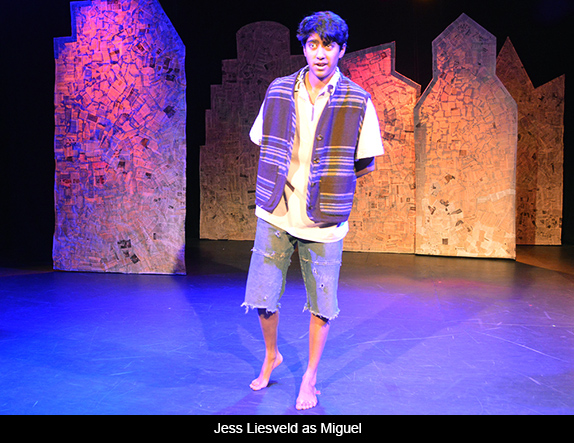

Bocón! (big mouth in Spanish) is about how violence and abuse result in voicelessness; and how empowerment, in whatever circumstances, requires claiming one’s voice and learning to speak out. The play tells the story of 12-year-old Miguel (played flawlessly by young female actor Jess Liesveld) who flees a repressive Central American military regime for a new life in Los Angeles. What he has been forced to witness literally renders him mute. Along the dangerous route he meets up with La Llorona, the legendary Weeping Woman of Mexican and Central American mythology. Through their magical friendship, Miguel recovers his voice and the courage to continue his journey. His story is important for immigrant children from all parts of the world, and for any child (or adult) who is learning the many meanings of finding his or her voice.

Spanish expressions mix seamlessly with English in this play; even an audience member who knows no Spanish at all will understand every line. Mime is also used to profound effect. During the part of the performance in which Miguel is rendered mute, his silent mouthing of lines is superb and evocative.

Sonya Tijerina is extraordinary as La Llorona, imbuing the role with flashes of comfort and humor as well as its darker side. At one point she tells Miguel: “You must find your voice! Porque…who can live without a voice in this world? Without a voice, you have no story…no one knows where you come from, why you are here…without your voice, you disappear.”

In these desperate times, disappearance is real as well as metaphorical. It has long been a terrible weapon waged against those who are poor, any color but white, female, different, or raise their voices against injustice and inequality. In Albuquerque we have wrenching examples of the disappeared in the still unidentified women’s bodies buried on the West Mesa, and in the ongoing victims of APD’s unchecked brutality.

Throughout Latin America, in the 1970s and ‘80s, military dictatorships literally disappeared tens of thousands of young people: 40,000 in Guatemala, 30,000 in Argentina, and thousands in other countries. But disappearance is not a phenomenon of the past. Just this month the bodies of 43 disappeared students in the Mexican state of Guerrero have been unearthed after weeks of searching. The students had attended a rural teacher’s school where resistance to rampant police/organized crime activity was encouraged.

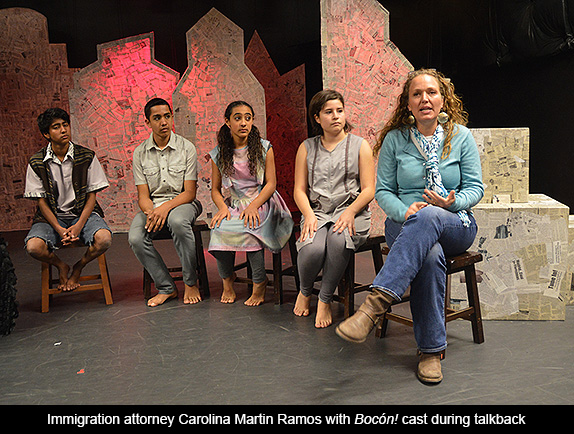

I was fortunate to see Working Classroom’s Bocón! on Sunday, November 9th. It will be performed again on the 14th and 15th (at 7 p.m.) and on the 16th at 3 in the afternoon. Some performances are preceded by food and drink for an extra donation. The showing I attended was followed by a talkback with the director, actors, and immigration attorney Carolina Martin Ramos of Justicia Digna. The latter spoke about the Artesia, New Mexico detention center where hundreds of young mothers and their children are currently being held for deportation, enduring obscene, frequently criminal, conditions before being sent back to places where they often face much worse.

Martin Ramos described women being brought before magistrates who will decide their fate, without the preparation that would enable them to respond correctly to questions. She reported on the prohibition of bringing even crayons to the children, inedible undercooked food, women so anxious or afraid they are unable to nurse their infants, and guards who offer baby formula in return for sexual favors. Children are particularly vulnerable in the detention centers. Mothers are often forced to tell their stories in front of their children, and are unwilling to do so, not wanting to subject them to stories of torture, including rape.

The deplorable conditions in such centers all along the border have been the subject of a number of recent news articles, while both our mainstream political parties continue to spew meaningless rhetoric about immigration reform and an administration that has long promised such reform fails to enact it.

Raising consciousness about immigration and other social problems is clearly beyond the concern or intention of today’s politicians. Ordinary people must take these issues into our own hands. Working Classroom is doing just that, in a powerful and extremely moving way. Audiences are educated. One young man, during the talkback at the performance I attended, said he had come to this country illegally, and pointed out that no child really knows he or she is “illegal.” He attested to the fact that Working Classroom has given him a space to exercise his own voice.

But if theatergoers benefit, for participants the experience is life changing. When the actors responded to audience questions, Sonya Tijerina’s testimony left a profound impression on us all. She said: “I am 19 now, and I’ve been with Working Classroom since I was 12. Through my participation I was able to come to terms with events I’d suffered in my own life. I want to go into professional theater, but not the theater of Hollywood or Broadway. I want to work in the theater of the oppressed.”

Sonya’s use of the term “theater of the oppressed” reminded me of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. The simple but powerful idea behind both terms is that when learning or acting or any other endeavor reflects one’s own experience, the outcome is qualitatively different from when one studies from an alienating textbook whose subject matter has nothing to do with one’s life. In the former case, experience is embodied and becomes a tool for change. In the latter, rote memorization and boredom often result.

I asked about Working Classroom’s audition process, and members of the cast explained that they don’t hold conventional calls for specific roles. Rather, those interested in being in the plays attend sessions where they experiment with a variety of parts. Actors are chosen on the basis of their ability to embody a role. “Males may be chosen for female roles, or females to play males,” one of the actors said. “Gender and race don’t matter.” This was evident in this particular play, where the male lead was played beautifully by a young woman, several other roles were gender-unspecific, and two guard dogs were also ably portrayed by young women. The serious professional training is obvious throughout.

Bocón! is a must see in Albuquerque’s fall theater season, and in and of itself. Don’t miss it if you can possibly make time to go. You can purchase tickets by calling 242-9267 or going on line (www.workingclassroom.org). I guarantee you will be glad you did.

Responses to “Working Classroom Gives Us “Bocón!””