Author's Note: This was originally published as an Op-Ed in the Albuquerque Journal on June 27, 2010. We were still suffering from extreme hope at that time, waiting for the “hope” president to end these Bush-led wars, which as we all know, our government started because of oil. Oil is the most important substance on the earth (water will overtake it soon) and no matter what anyone says or argues or postulates— It’s the oil, Stupid! So we’re still there, back on the same track, with Bush now a long faded image.

There are many lessons in the pages of our nation’s history, which we seem unable to assimilate, so we must repeat them in an endless cycle of disillusionment and destruction. We appear arrogant in our dealings with other nations, unilaterally deciding what’s best for the world, at the same time endlessly proselytizing about democracy. When foreign nationals feel that their internal lives are being manipulated and disrupted by U.S. intervention through military and monetary power, a blowback is inevitable. The infamous outlaw and revolutionist Pancho Villa raided the United States in 1916, his actions being an example of this backlash; we may extrapolate this lesson to September 11, 2001.

By the fall of 1915, Francisco “Pancho” Villa and his División Del Norte, once the greatest military force in Mexico, had been subdued into surrender. The government of Venustiano Carranza and General Obregón had offered the insurgent army a general amnesty, which included ten gold pesos per soldier; Villa’s 16,000 men put down their weapons. Most experts agree that Villa, who had refrained from taking control of the large haciendas in northern Mexico, had not built a permanent land reform policy that would ensure lasting changes for his largely peasant followers.

Villa did not surrender, however, nor did he go into exile. With his famed “El Dorado” cavalry he reverted to his bandit past, raiding and stealing, and settling old scores against those he felt had wronged him or, worse, betrayed him by supporting the Carranza government, whom Villa felt had betrayed him and their cause. Villa was also angered by President Wilson’s support of Carranza and the fact that the U.S.-owned mines in Sonora had shut down, an act that caused widespread suffering among the workers. And Mexicans were still bitter over the military intervention of the U.S. at Vera Cruz, in order to support the Carranza government against General Huerta. On top of this, anti-Mexican sentiment in Texas had led to the vigilante deaths of hundreds of Mexican-Americans, including twenty Mexicans who were burned to death in El Paso just two days before the raid.

General Villa had much to stew over. Being a man of action he decided to level his retribution on the North Americans. He captured and shot sixteen U.S. mining engineers traveling by train near Santa Isabel, Chihuahua. Then he pillaged a hacienda owned by William Randolph Hearst, the San Francisco news lord. These antagonistic actions clearly conveyed the message that his hands-off policy toward norteamericanos had been reversed.

His next act—although insignificant as a military operation—would enter into the history books as a unique event: Villa invaded the United States. On the night of March 8, 1916, Villa led about 400 men through the chaparral where they breached the border a few miles south of Columbus, New Mexico, a sleepy settlement of only 300 residents. Villa’s plan was to wait until the early morning and raid the town and its bank. This was the first time since the War of 1812 that U.S. soil had seen foreign troops bent on causing death and destruction.

The Mexican Revolution followed a complex scenario, but it had begun during the elections of 1910. Villa had been a major player from at least the following year, and during that time he did not vent his hostilities on U.S. citizens or their property. In fact, he lived for a period in El Paso, and purchased arms from dealers on this side of the border. He sold beef to Texans and always operated with the hope that the men in Washington would be sympathetic to the cause of the Constitutionalists. He spared the large haciendas and foreign-owned property in general (although he expropriated their cattle, for which he paid the price of making some important Americans very upset, like Col. Harrison Gray Otis who owned the Los Angeles Times) and was content aiming his energies at the counter-revolutionaries—so why did Villa now turn his rage against the United States? For one, he felt betrayed by Washington, because President Wilson had backed his foe.

The raid began sometime after 4:00 a.m. The garrison as well as the citizens were caught by surprise, families were awakened by what they “thought was hail on the roof.” Some testified they heard Villa’s voice “everywhere.” By 7:30 the town was a smoking ruins, 18 Americans lay dead and 90 Villistas had been killed. Villa’s men withdrew with 80 horses, 30 mules, and at least 300 Mauser rifles, a dubious victory considering the number of dead. But booty was not their avowed purpose, as Pablo Lopez, one of Villa’s officers said, “We want revenge against the Americans.”

Villa was not planning to occupy Columbus, nor claim the territory for Mexico; the raid was more an act of terror, one he was hoping would cause embarrassing repercussions for the government in Mexico City. The tactic worked, tentatively, as Mexico and the U.S. sparred and jousted for weeks, taking them to the brink of war, until Carranza promised to release U.S. captives and pursue the bandits.

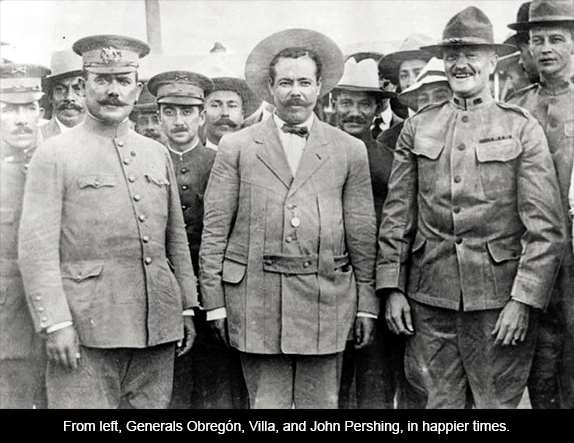

Figure 1 From left, Generals Obregón, Villa, and John Pershing, in happier times.

Whatever logic or political motivations were behind the attack, there were good reasons to attempt to plunder Columbus. The U.S. Army had garrisoned a few hundred troopers there, so there were supplies and animals, as well as arms available. The bank had accommodated the military by adding cash for their payroll, and a merchant by the name of Sam Ravel, who had supposedly cheated Villa on a shipment of rifles that the general had paid for in advance, operated a mercantile store on Boulevard Street. Luckily Ravel was out of town, the story goes, visiting his dentist in El Paso; another tale has him hiding under a pile of hides while his store was looted.

Of course the public expected an armed response. One week later a force of 4,800 troopers under the command of John J. “Black Jack” Pershing crossed the border with orders to disperse the Villistas and capture their leader. After a year, they had not accomplished this feat, had not even glimpsed Villa; worse, their presence only inflamed anti-American sentiment in Mexico. Pleased with the efficacy of his tactics, General Villa raided Glenn Springs, Texas, in the Big Bend, as well as Dryden, at Eagle Pass, with American troops giving hot pursuit. The Mexican press, with Carranza’s urgings, attacked the U.S. and President Wilson was warned again that the situation could spark a war between the two countries.

New Mexico was on everyone’s minds during this time, this event reached around the world, as newspapers everywhere retold the story of the Mexican bandit who had attacked America, as well as the pending outbreak of war between the two nations. Columbus began to attract tourists and eventually a museum commemorating the attack was installed inside the old train station.

Ironically, this lawless act of revenge has become a permanent part of the culture of New Mexico.

Ninety-nine years ago near a dusty border between two neighbors a dispute broke out because one of the neighbors was interfering in the domestic affairs of the other one. Isn’t it time for us as a nation to discard our “shock-and-awe” policies and begin to fathom and shape more positively and honestly the image that others hold of us?

This is what we were hoping our new president would accomplish, along with showing a new face in foreign policy, so we could begin to reshape our image so the rest of the world would respect us once more.

This would be mundane if the consequences were not so dire.

Responses to “Why, Pancho, Did You Invade New Mexico?”