Perhaps a hundred members of the New Mexico political class munched brie, signed petitions and tossed $5 bills into the hopper July 10 at the home of former state Sen. Dede Feldman, but if there was a Republican in attendance, he or she was hiding in the warrens of the custom-designed house. That fact tells you a lot about the politics of marijuana reform.

The multi-pronged drive to ameliorate the state’s harsh pot penalties brought these political activists together. The specific effort was to raise money, gather signatures and solicit support for petition drives in Albuquerque and Santa Fe to put proposals on the November general election ballot. The proposals in both cities would eliminate any jail time for first-time possession of less than an ounce of marijuana and reduce the maximum fine from $50 to $25. A more far-reaching proposal cleared the state House of Representatives but not the Senate, and a constitutional amendment failed earlier this year.

Gov. Susana Martinez has threatened to veto reform proposals. She has also been negative about the state’s medical marijuana law, which her administration has been trying to restrict, but in the face of an outpouring of opposition at a public hearing earlier this month, at least some of the restrictions seem likely to die.

Blocked on other avenues, reformers have turned to the unusual device of gathering signatures on petitions. If they get sufficient support, the city councils in the two cities will have to either pass an ordinance or send the measure to the voters.

Already in Santa Fe, petitions signed by 7,126 registered voters have been turned in, more than the 5,763 required minimum, although the validity of the signatures has yet to be verified by the county clerk. Santa Fe plans to verify the signatures by July 25. If there are enough verified signers, the city will hold a public hearing on the proposal Aug. 27. Some city officials, including the mayor, support the petition.

In Albuquerque, the reformers are working against a July 28 deadline.

In both cases, the goal is not just a popular vote but a vote on Election Day, Nov. 4; not just to reform pot laws but to give reform advocates an incentive to go out and vote in what is shaping up as an unexciting low-turnout election. It just happens, former Republican Gov. Gary Johnson and his libertarian supporters notwithstanding, that most of the advocates of marijuana reform are young, liberal—and, as the turnout at Feldman’s home indicated, Democratic.

Thus, the Drug Policy Alliance and Progress New Mexico, which are leading the reform effort, calculate that having reform measures on the Nov. 4 ballots in Santa Fe and Albuquerque would increase Democratic turnout, helping the endangered candidacy for governor of Gary King and perhaps rescuing control of the House from a big-buck Republican onslaught.

The double-barreled campaign of idealism and calculation, of pot reform and Democratic victory, is what has given fire to the campaign and increased its chances of success.

The actual changes the proposals could accomplish are hard to predict. In the short term, every policeman and prosecutor in the two cities would be faced with a choice: whether to charge an offender under the new lenient city ordinance or the harsher state law, where up to 15 days jail time for a first offense would still be possible. Reformists are gambling that most cops and prosecutors would choose the city ordinance because it would be easier and cheaper to secure a conviction. For the offender, what he would have on his record would be a citation comparable to a traffic ticket rather than a criminal charge that could shadow him all his life.

In the long term, the votes would be indications of the strength of pot reform in New Mexico and thus spur further efforts for change. New Mexico led the way with one of the nation’s first medical marijuana laws, and since then repeated efforts have been made to move toward decriminalization or even legalization. Just about all those efforts have been led by veteran state Sen. Jerry Ortiz y Pino, who spoke briefly at the Feldman gathering.

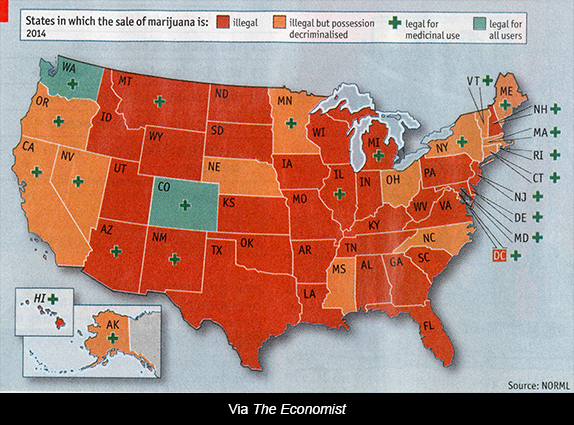

Nationally, the movement has made considerable strides. With the recent addition of New York, 23 states now allow production, sale and use of marijuana for medical purposes, mostly to relieve pain. In some states such as California, these laws are so loosely worded and poorly enforced that just about anybody who wants to can legally use marijuana.

A majority of Americans tell pollsters they favor legalization. The U.S. House of Representatives has voted to eliminate all money from the budget to pay for raids on medical marijuana facilities. Although such facilities remain illegal under federal law, by tacit understanding the law has not been enforced.

Full legalization now exists only in Colorado and Washington. But two more states, Oregon and Alaska, are to vote on legalization in November, and a half dozen more, including California, will probably vote in 2016. Legislatures in most of the New England states will be voting on whether to legalize pot.

Internationally, only one country, Uruguay, has achieved full legalization, but many other countries, such as Denmark, Germany, Holland, Portugal and Spain have moved in that direction. Mexico has legalized possession of small amounts of all drugs. The seven Central American countries are discussing legalizing marijuana and perhaps other drugs as a way to stem cartel violence. The drug gangs have virtually taken over Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador and are causing lots of trouble everywhere in the region. One result has been the recent onslaught of Central American child refugees showing up at the borders of New Mexico, Texas, Arizona and California.

Reform proposals are also piggy backing on other issues, including prison overcrowding and budgetary constraints, with the result that they have picked up momentum in some surprising states such as Mississippi, Texas and Florida. Texas has done such a good job of reducing its prison population that Bernalillo County is now looking at it as a model for reform. An Oklahoma state senator maintains the Bible supported legalization when it stated, “God said behold I have given you every herb-bearing seed…upon the face of the all the earth.”

How far the reform movement reaches in New Mexico may be determined by who wins the gubernatorial election in November. While Martinez, who has spent most of her career as a prosecutor, opposes all the reform proposals, her opponent, King, has changed his position, according to Ortiz y Pino. At the Feldman gathering he said King implied in a conversation with him that he would announce support for decriminalization.

At the least, marijuana may add some fire to the upcoming election campaign. As the saying goes, where there’s smoke, there’s fire.

(Photos: Susana Martinez by Steve Terrell, marijuana by Dank Depot)

Responses to “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire”