Throughout the world, foods are some of our greatest cultural assets. They do so much more than feed our bodies. They speak sustenance, survival, generosity, and hospitality. Their scarcity can mean death, their overabundance body image disorders. Their roles in community celebrations are jubilant. When they are rationed, as they were in Cuba when I lived there in the 1970s, it can be experienced as hardship or as joy in no one going hungry. An extra place at the table is a stalwart in many cultures.

My own childhood didn’t come with recipes. My father’s favorite meal was hot dogs and sauerkraut, and Mother’s widely advertised spaghetti was too heavy on the Velveeta processed cheese to be a part of my eating today. We had the typical middle-class U.S. American Christmas and Thanksgiving dinners—the former as one of many cover-ups for our carefully assimilated Judaism, the second despite the fact that later in all our lives this celebration of European assault upon the country’s indigenous population would prove distasteful: not a tradition any of us would nurture. Today, although I confess to loving roast turkey, stuffing, and homemade cranberry sauce, we often skip the traditional meal for a visit to the Apache Bird Refuge, where we can see the winged creatures live, in their natural habitat. My grandmothers might have had recipes for strudel, borscht or other old country Jewish dishes. If they did, I never knew about them.

As an adult, I have traveled the world, looking and listening, and savoring. Breathing in the scents of unfamiliar foods, experiencing not only their myriad tastes, but also what they tell me about how other peoples live. In Africa and the Middle East spice markets are filled with aromas that entice me even when they are unrelated to anything I have known.

In Uruguay, the asado is like and unlike our bar-b-q; it is meat on a grill but that’s where the similarity ends. The asado is pure ritual. Each part of the cow is prepared and served in its own way. Offering the outdoor meal is a skill passed down from generation to generation. Like mate, the bitter herb infusion sipped through a silver straw from a gourd carried everywhere by Uruguayans and Argentineans, it is a food custom typical of the people who live along the Río de la Plata.

As with music and poetry, a nation’s culinary art is a central part of its culture. Favored foods, and how they are prepared, define countries and regions within those countries. Some, such as China, Mexico, France, India, Italy, and Vietnam, have such a variety of food traditions that thick cookbooks have been written about them, and films produced in which particular dishes are central characters. In all these places, as well, hunger is a terrible presence. Bread, called “the staff of life” almost everywhere, anchors the human diet from the time of fire and grinding stones. In many countries the poor person’s table offers a rudimentary flat bread, that often acts also as a spoon, while the social status of the rich is defined by “proper bread.”

In every country in the world, both the plentiful table and the child’s belly bloated by hunger are messages that speak competing truths. Images of vast refugee camps, where international aid organizations provide basic rice and gruel vie with those of exclusive eateries where the wealthy spend upwards of $1,000 dollars on a single entrée. This astonishing contradiction, which most people seem to take in stride, is not unlike the stuffed crust pizza commercial that flits across our television screen followed immediately by the commercial for a diet plan or exercise equipment: globalization at its most absurd. In Southeast Asia giving alms to Buddhist monks is an essential part of everyday life.

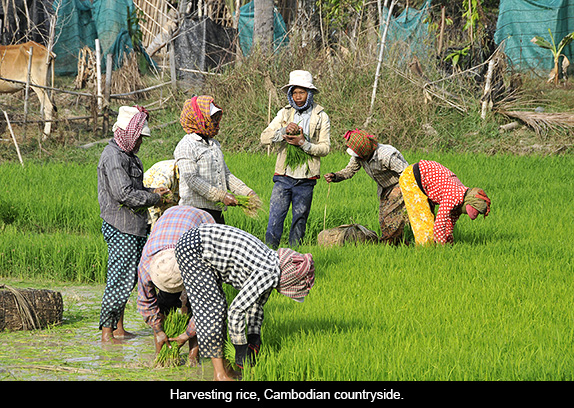

Whole parts of the world are defined by whether they are rice cultures, corn cultures, or wheat cultures. These grain staples depend upon climate and the properties of the earth. When we think of China or Vietnam we automatically think of rice. When we think of Mexico and Central America we think corn. Wheat comes to mind when we consider French bread or Italian pasta. These food staples are so deeply entrenched in national cultures, so important to the food expectations of their peoples, that it is difficult to imagine what will happen when climate change turns weather and growing seasons upside down.

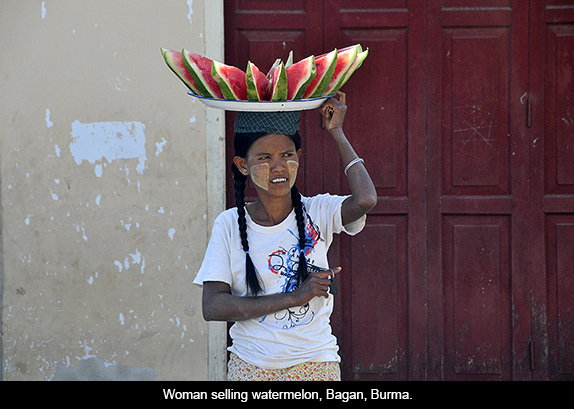

Familiarity in food is comforting. And so a woman with a tray of fresh watermelon slices on her head in Bagan, Burma may remind us of eating the same fruit in the southern United States. Or a young girl offering us a raspberry right from the bush in the tiny village of Gromaca, Croatia may make us feel at home in ways we may not be able to immediately decipher. The fact that the Burmese vendor’s face is painted with swatches of white clay, or the Croatian child and we don’t speak the same language, are issues that fade in the face of food recognition.

Everywhere people offer their unique dishes with special pride: Guatemala’s silky tamales wrapped in banana leaves, Belize’s freshly caught fish, South Africa’s vegetable stews, Navajo mutton, Vietnames Pho, Italian pastas, and more. The ordinary becomes extraordinary. Often the most delicious of these dishes are those that are everyday fare for the country’s native population.

Surely one of the travesties and tragedies of our time is that food is no longer what it once was. No longer can we trust it to be uncontaminated, free from genetic modification, or devoid of the hormones, pesticides, or radiation we can’t taste at the moment of eating but that will come back to hurt us in the long term. Even movements demanding the proper labeling of what we buy—designations such as “organic” or “natural”—have come to mean very little. The giant food lobbies have managed to twist these labels so they don’t mean what we are led to believe they do.

I have so often observed with delight, in countries less industrialized than ours, that a tomato tastes like a tomato or an apple like an apple. Here, unless we grow our own or shop at local farmers markets, we tend to forget those tastes. Untreated vegetables may wilt sooner than ours, but the chemicals used to keep them looking fresh are counterproductive. Pandemic obesity, generations of eating disorders, and famine-size hunger are all too common in societies with dangerously skewed priorities. As long as we demand foods that are not in season and specialties from halfway around the world, we contribute to a food unbalance that hurts us all.

Responses to “What We Savor: Food that Makes Memory”