Here’s one story. A big British bank with a bad reputation sets out to exploit a poor vulnerable city in order to recoup its bankruptcy losses. Vulnerable city fights back with good values born of tradition, love of place, and justice.

Here’s another version. Developers set out to help a poor city with economic development in an earth-friendly way via new housing and jobs. Stubborn and uninformed local groups resist and stall their efforts.

There is of course truth in both stories or else we wouldn’t recognize them. But the case of the proposed Santolina development just outside of Albuquerque—where these stories summarize two of many positions in the debate—drew me like a moth to a flame. I decided to attend the Bernalillo County Commission hearings on the proposed development in Albuquerque on March 25th and 26th. I sit now with scorched wings and fried antennae to try and show Mercury readers what I learned about why those two stories are among many portals into a poorly lit labyrinth.

I walked into the Vincent E. Griego Chambers, a comfortable and well teched-out space, though the fenced-in bullpen and the elevated semi-circular wood dais behind it felt a little like a cross between a cathedral and a tribunal. The seats filled pretty much to capacity, islands of yellow t-shirts scattered throughout the room imprinted with "Santolina Denied" logos. A rally and protest march of about 150 people preceded the hearing. The back of one t-shirt on a person standing next to me said “WTF” and, underneath, in smaller print, “What about the future?” A couple of people walked the aisles passing out material that raised questions about the proposed development. Clearly not a wildly supportive crowd.

The chair knew how to pound a gavel. The crowd buzz died like a swatted fly. Here we go, I thought. But no. First we go elsewhere. The previous Monday one of the commissioners, Art De La Cruz, had surprised everyone by writing an op-ed piece for the Journal. The heart of it, I think it’s fair to say, was that growth is inevitable and it’s better to plan for it, control it, and ensure that the county benefits by it. That’s the reason, he wrote, that he supported the new “planned community” development. The argument is reasonable, and it isn’t his alone, but should a commissioner publish his conclusions right before a County hearing meant to gather information? The Environmental Law Center thought not and pulled a legal lever to force the Commission to answer that question before anything else happened.

Here comes one of those boring things that turn out to matter a lot. Was this hearing a “quasi-judicial” or a “legislative” proceeding? This is not a difference that many Mercury readers have ever lost sleep over. But here it mattered. If the former, then the commissioner should "recuse himself"—legalese for a red card that ejects him from the game. And if he refused to go gracefully, the other commissioners should ask him to leave.

This consumed a fair amount of the time meant for the opening half-day session. Eventually the Commission refused to move to re-move him from the hearing, though Commissioner Debbie O’Malley spoke a bit about how this didn’t look good. She had in fact thought it was quasi-judicial and had refused to speak to people about the issue while it was still in process.

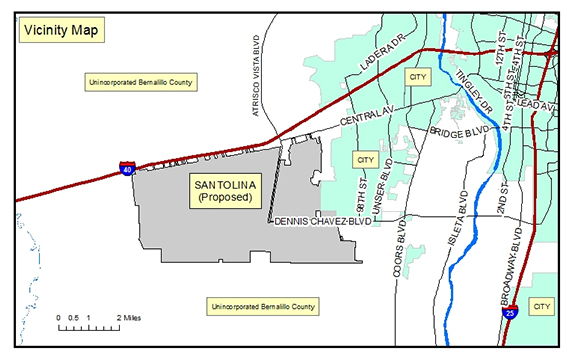

Finally, then, on to the proposed Santolina development plan. In case a reader doesn’t know, here’s a map from the proposed plan, which was also featured in an earlier piece in the Mercury.

This is obviously one serious patch of desert. Long story short, Barclay’s repossessed it from SunCal in 2010, who had acquired it from Westland in 2007, who had purchased it from the original Atrisco Spanish Land Grant, a story described in Joseph Sanchez’s book about the grant, Between Two Rivers. The land is now managed locally by Western Albuquerque Land Holdings, LLC.

Why is Santolina even happening? It begins, as far as I can see, because Barclay’s wants some cash back from its repo. I have nothing against global trade. I have a lot against too-big-to-fail banks based on their past and current behavior. Local pro-development voices, as you’ll hear in a moment, were reasonable. But I admit to a bad attitude at the beginning given the monster behind the proposed development.

According to Damon Scott in the Feb 6th Albuquerque Business First, the development covers 13,700 of the 57,000 acres that Western Albuquerque Land Holdings manages. The plan is to grow it over a forty year period, eventually including as many as 38,000 households, 90,000 residents, and the promise of 75, 000 jobs. It is part of an “I-40 corridor” concept for growth of the city. Albuquerque pretty much has to grow that way, since it has mountains to the east and Pueblos to the north and south.

Much has been written about Santolina, with much more to come, by people who know the intricacies of urban planning and development, pro and con. I’m no expert in those fields. But I’d like to zoom in on a couple of things that struck me, a language-oriented social researcher, as I worked to make sense out of what was being said.

We language nerds talk about “discourse” a lot. All that means is that a certain kind of person or certain kinds of events require use of the corresponding language as a condition of participation. If you address the Commission Chair with “Yo lady chair dude” you’re on your way to the exit. On the other hand, if Chairwoman Stebbins talked to the homeless people near the convenience store I walked past on the way to the hearing and said, “Call me Madame Chair,” she probably wouldn’t get very far either.

Figuring out the discourse in the Griego Chambers, I felt like a fresh arrival in a foreign land. I spent a day and a half-listening and conversing with other members of the audience. By the end I was having a “Newspeak” problem, if you remember Orwell’s novel 1984. The discourse I was trying to figure out to understand how a decision was made. At the same time it made it impossible to nail down the information needed to make that same decision. Santolina, yes or no? Sorry, can’t come to any conclusions right now, because the discourse rules say it’s not time to do that yet. Confusing? Read on.

Here’s one key discourse marker that appeared early and then re-appeared over and over again during the two days. It goes by "Level A, Level B and Level C.” Advocates of the development, like Commissioner De La Cruz and the consultant who presented the plan in detail, referred to this “Level discourse” as the reason for major misunderstandings between the process and the public.

Well, of course there’s a misunderstanding. People like me, the public, come to the event to debate on whether or not we support Santolina, period. People who speak County Development Discourse come to the event to decide if they approve “Level A” so they can keep going and get more information at “Level B” to decide what information they need at “Level C” to finally decide if someone should actually “shovel dirt” and build a house. There’s plenty of time to “drill down” later—a metaphor with plenty of resonance in New Mexico. No commitment, no detail, not at Level A, let’s just talk about this thing and see if we want to talk some more.

In this case, the discourse got weirder still. The A-level plan had already been approved by a split vote, subject to a list of “considerations and findings” that the Commission added. That translates into “changes in the plan that the County added, with their approval conditional on developer acceptance of those changes.” But the developer, between that earlier meeting and this one, had officially challenged some of them. The Commission had to rule on those challenges, but they were the final item on the agenda. So what was being discussed really? A plan that the Commission might or might not reject at the end of the hearing?

I’m balanced on the tip of a melting iceberg here and there’s much more to tell. But so as not to overload the limits on The Mercury’s digital storage, let me just “drill down” into a couple of examples.

Commission staff, one after another, presented details of what they had done to evaluate the Level A plan—water, open space, transportation, economic development, etc. They all concluded with support to move on to Level B. Remember, in principle “B” is not a decision to do anything, but rather a decision to talk about the plan in more detail. But—here’s the Newspeak problem—questions from Commissioners, and later comments from “the community,” usually focused on the characteristics of a finished Santolina, not just the question whether or not the Commission and developer should keep talking.

Consider the water guy from ABCWUA, the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority. Santolina is outside their service area and would have to be brought into it. Part of the “A” plan is a letter from that agency saying yes, they have the water the development needs. He carefully noted that the letter didn’t commit to actually doing anything and added that Santolina would have to show satisfactory plans for infrastructure, conservation, and water-efficient technology. And where would the new water come from? Conservation, new plans for aquifer recharge and wastewater recycling, better technology now available to new construction, things like that. Drought, climate change? ABCWUA plans for the future weren’t required for the letter. All they had to deal with at this Level A stage was, "are we capable of providing enough water, yes or no?" The answer was yes.

How much water does Santolina need? For a guesstimate, let’s use the end figures for the development, an estimate of 90,000 people. Now consider Bruce Thompson’s presentation at the Water Assembly 2015 conference, “Climate Disruption and Our Water Future: Mitigate, Adapt or Suffer—A Call for New Strategies.” He presents slides of the water budget for the Middle Rio Grande, one slide specifically on “Municipal and Industrial” use. The slide includes Albuquerque, but also Rio Rancho, Santa Fe, Belen and Socorro. “Consumption” of water equals what cities and industries take out minus what flows back into the river and the aquifers after they use it.

Roughly, cities and industries in the Middle Rio Grande take 30,000 acre-feet per year out of the river, but they send 71,000 acre-feet back in. They also pump 98,000 acre-feet per year out of the ground and return only 4,000 back into the aquifer. So their net consumption of water in a year is 53,000 acre-feet per year.

Let’s also use Thompson’s figure of 130 gallons per day per person water consumption in Albuquerque, a remarkable decline from the 1994 figure of 252. In fact, Commissioner O’Malley noted that all the effort the city and its citizens had put into conservation helped understand resentful questions about a massive water demand from a new development.

So 90,000 people at 130 gallons per person per day, doing the arithmetic, comes out to 13,104 acre-feet per year. That doesn’t include use by the planned Santolina business/industrial park and the local businesses that would serve residents. If we estimate a 52% rate of consumptive use from Prof. Thompson’s slides that means Santolina will consume 6,814 acre-feet per year for residents. The additional amount for commercial and industrial use I don’t know how to guesstimate.

Is that possible? Can the tangled web of rights, leases and permits, and new technology be manipulated to handle that demand in the years that the development grows, years when the big picture looks more and more like reduced supply from groundwater, snowmelt, and the San Juan/Chama—all three?

Whoops, I’m drilling down, not a Plan A agenda item. I have no idea if my guesstimate is in the ballpark, nor what the situation with rights and “wet water” and technology is and will be in the future. Without that information, how am I to know if Santolina makes any sense or not? The ABCWUA guy, by the Level A rules, doesn’t have to answer such questions or provide these and other data. ABCWUA just had to write a letter that they could supply what Santolina will need, or not, that’s all. Trust them, they can do it. More information if we go to Level B, and more again at C.

There are many, many more examples of hitting this Level A wall. Just one more here, the economic development presentation. Santolina promises a new tax base, businesses, jobs, all this following the “no net” rule, in other words, the rule that the county will not pay a penny, that it will actually benefit from the economic activity and revenue of its new citizens. Such a deal. I believe that this is one of the “conditions” that the County added, that this “no net” was guaranteed by the developer. It is also one of the conditions that the developer challenged.

The young staffer who presented the analysis concluded, like the others, that the Santolina plan should be supported at Level A, though the figures were provided by the developer. Two other models were a little less cheery on how it would go. Then, in response to questions, especially from Chairwoman Stebbins and Commissioners O’Malley and De La Cruz, she lifted the cover off the analysis and showed the assumptions it was based on. I hope she becomes governor some day.

One question was, what if it turns out that no one wants to move there? Population growth has declined in the city and other planned communities in the area haven’t done so well. The analysis, she pointed out, like most of its kind, assumes a “build it and they will come” result. But will they? Who knows? Commissioner De La Cruz presented an example of how new business could be developed and make a difference. He invited a spokesman from a company named Foods of New Mexico to describe how that particular business did indeed bring revenue and employment into the county. I was impressed, though it is a food distribution company, not a real estate development.

And what about this “no net” deal? The City and County won’t have to pay a penny? Well, not exactly. When the developer presented the plan, questions from commissioners flew through the air like annoyed bees.

The developer promised to take care of those parts of the development that were for the use of Santolina residents. But other parts would be of value to non-residents as well. The County or City would pay their fare share of those. How did they propose to figure out what was shared and what the developer percentage for those things should be? Not a Level A problem.

Then I learned another piece of new discourse, the TIDD. It stands for “Tax Increment Development District.” A TIDD, originally designed to encourage renovation of depressed areas, means that some of the property and/or gross receipts tax that a new area produces is returned for construction of public spaces in that area. Did the developer plan to request a TIDD to cover some of its costs? Some Level A waffling ensued. No, yes, maybe so, or maybe a TIDD shouldn’t count as breaking the no net rule. We can drill down later.

I could go on and on here. Transportation for example. If the Santolina business park didn’t fly and new residents had to work in Albuquerque, would commute traffic across the Rio Grande Bridges add to the mess that Rio Rancho has wrought? An expert consultant joked that projections showed that, under certain conditions, you’d get to work faster if you walked.

I can no longer tell what might be dull and what is interesting to a reader. In fact, I left after the second day thinking, “This is a book, a story that contains in microcosm the major ins and outs of what Albuquerque, Rio Rancho, and Bernalillo County might turn into.” But for this highlights of the hearing for the Mercury, I want to shift gears now and say something about the “community” comments.

“Citizen” might be a better term to describe the variety of people who spoke before the Commission. “Community” of course also means “citizens,” but it seemed to be used more as a code word for people who lived in the Santolina area, the “South Valley,” primarily native New Mexicans whose families have been here for generations, some of them actual heirs of the original Atrisco Land Grant awarded by the Spanish Crown in colonial days.

Many of those who rallied and marched and filled the auditorium with yellow t-shirts—South Valley community and others—had planned on the first day schedule. But with the legal arguments about Commissioner De La Cruz’s column, statements were postponed until the second day. Many couldn’t return because of work and kids, but the Commission did allow some proxy readings of prepared statements.

The problem is that a person—“community/citizen” or ordinary “citizen”—only gets two minutes to speak, and the sequence of presentations is uncoordinated, so content, besides being extremely limited, jumps from one perspective to another. The Commissioners didn’t spend the time checking their email on their smart phones, though. They concentrated and listened, almost always. I watched their eyes.

One thing was clear: Statements were overwhelmingly against the development—the development, period, not the Level A plan. There were many different two-minute reasons, most all of them worth hearing, some of them worthy of much more elaboration. For example, the manager of the Atrisco community said that the original sale of the land grant remains in dispute so the land titles aren’t clear. A UNM grad student had wandered the Internet and found earlier reports that the land shouldn’t be developed at all. An acequia specialist outlined how little we actually know about who has what water rights, permits and leases and how rights for Santolina would be handled.

An eloquent two-minute opposing statement was rewarded with applause. The few supporting statements—though reasonable—were met with dead silence at the two-minute bell.

For a good example of some “community” and/or “citizen” views, a reader could visit the New Mexico Mercury and Albuquerque Journal web pages and look for guest editorials prior to the hearing. In particular, take a look at Virginia Necochea's reply to Commissioner De La Cruz’s controversial editorial and take another look at the video of her interview with VB Price on The Mercury web page. She put in her two cents—I mean two minutes—worth at the hearing as well. Her editorial and video interview will show you how a two-minute comment by a critic of Santolina pales in the face of what the same person has to say when allowed a reasonable amount of time.

In an earlier Mercury article, I complained about how “community participation” at a water hearing I attended was poor social science. Community/citizen participation was limited and superficial there as well. The endless sequence of sound bites at the Santolina hearing was just another example of the problem. There are many ways to develop more profound and systematically based knowledge of diverse points of view on a difficult issue, from translation/interpretation theory, from conflict resolution, from organizational development, from ethnography. There are also special elections on specific issues. A couple of the two-minute comments suggested exactly that.

Albuquerque Business First ran a poll before the hearing asking readers to vote on Santolina. With 671 responses, 57% voted “no.” Not a systematic sample, not at all, so hard to tell what the results represent, though probably the readership of Business First isn’t a hotbed of communists. On the other hand, there was an effort to get critics to participate as well. I voted “no” myself.

At any rate, the overcrowded agenda spilled into the end of the second day. I had to leave a little early—comments were still going on—but by then it was clear that the Commissioners wouldn’t get to the appeals against the plan, which included the developer’s appeal against conditions from the earlier approval. And, sure enough, I read the next day that the final decision on Level A had been postponed and another hearing will be held in May. We’re still at Level A and holding.

Warning: Author’s personal rant starts here.

I left convinced of what the occasional talking head in the media says, that cities and counties are the future of political action in the United States. Washington is hopeless; New Mexico matched it this last legislative session. The hearing in the Griego Chambers, in contrast, was for the most part civilized and reasonable. It didn’t have the feel of a rigged game. There was plenty of respectful give and take. It was hard to feel like there was a major villain or a secret conspiracy. Even the developer’s representative, the usual Simon Legree suspect, presented some interesting concepts about the “complete street,” environment-friendly technology and open spaces. And many who spoke in support of Santolina seemed passionate about adding opportunity and wealth to a depressed city and county. It wasn’t only making some money and leaving town. Not from the voices in the Chamber.

A group of people of the quality I witnessed should be able to steer their local world into a better future. What’s the problem?

Here’s one: Learning my Level ABC’s made me feel like we were stuck with a process that resembled trying to run a slalom course down a ski slope on a ten by ten foot adobe brick. The proposal was first submitted in 2013. We’re still on Level A with no end in sight. If the Commission says yes, we go to B and do the whole dance over again, I guess. If the Commission says no to A, I bet the developer appeals in court. And I bet the court will be as confused as I am, because Level A isn’t about whether we should start throwing dirt in the air. It’s about whether we’ve talked about it enough to talk about it some more. How do you rule on the shape of things in that kind of Newspeak fog?

We have probably entered the Anthropocene, a time when Earth is changing into something different at an increasing rate, and we don’t know for sure what it will look like until we get there. The process that an issue like Santolina requires, or the Aamodt case that I’ve researched and talked about at other times, makes it impossible to know and react and learn and change what we know at a pace quick enough to make it through this transition from one geological epoch to another. The discourse around Santolina that I learned in my short two-day course in Albuquerque—it was enough to teach me that the present rules aren’t up to the job. It’s not the fault of any specific villain that we’re working with a system that is now dysfunctional. But it has to change, now.

Here’s another thing that occurred to me: I’ve lived in a lot of places, travelled to a lot of others, heard stories about more still. I thought about what kind of major changes I’ve seen that have lifted cities out of the depths and set them on a trajectory of turning into a better place? I couldn't think of a single case where a massive suburban development had done the job for any city in the U.S., not in recent times. On the other hand, I thought of several examples where a city put energy and money into its center, became something more lively, more creative, more stimulating, safer than what it had been before.

I know the jargon here is “infill” versus “greenfield”—I learned that discourse in the Griego Chambers, a name that is sounding more and more like the title of a SciFi novel. One two-minute commentator thanked Commissioner O’Malley for her support of “Sawmill,” an urban renovation project in Albuquerque. I took a quick look on the Internet. And I thought about the earlier testimony of the man from the food distribution company in the South Valley, a development strategy that seemed to me like it was locally anchored and had worked. I decided that my earlier “no” vote, based on my water mania, was too narrow and too specific.

My “no” vote now was based on how Santolina was the wrong answer to the right question. The right question was, what kind of city and county do “we”—in the most inclusive sense of the pronoun—want to move toward? Investment and incentives need to be part of that vision, obviously, but so do values and interests that derive from the kind of world we want to live in. That’s the quick way to Level ABC. You want to invest here? Here’s what we are interested in seeing happen. Does your plan contribute to our vision of the future? Otherwise let’s not bother with any ABC conversation at all.

I’m a Vaclav Havel capitalist. He said that a market is neither a morality nor a philosophy; it is only a means of exchanging goods and services. And for reasons too complicated to describe here, I’m influenced by post World War II Austria, where the economic idea of a “social partnership,” like the post-war German concept of “social market economy” was a way to grow out of destruction and poverty.

The core question is—it motivated both the pro- and anti-Santolina comments—how do we “develop” a region—the one we care about and live in—out of poverty and decline in a way that handles the way our planet is changing? Santolina and the planning process I experienced in Albuquerque echo the old solutions of the post World War II Western world, the period of time that the Anthropocene researchers call “the great acceleration,” when the human impact on Earth went into exponential overdrive and pushed the planet to the point where it now pushes back

We need a new way forward, with a vision of how we want to live and co-exist with our tempermental planet, capital helping to get us there with all the reasonable risks and rewards that will bring it into the project. I had this notion on my drive back to my own county that that roomful of people in the Chambers of Griego might just be able to create a new discourse and pull it off. Maybe they could change the rules, aim at a common future, and make the money work for them rather than the other way around.

I know, politically naïve and hopelessly optimistic, but better to die on your feet than live on your knees.

End of rant.

Responses to “What kind of plant is “Santolina”?”