Mexico has been in the news over the past decade, among other reasons because of its uncontrollable violence. Competing drug cartels kidnap and murder at will, and poverty is extreme enough that law enforcement, when not directly involved, takes bribes to protect the guilty. Corruption seems to rise to the highest levels, and despite notable advances some consider the country to be a failed state. When we say we’re going there, people often ask us if we’re afraid.

Perhaps. But we are just as afraid on the streets of Albuquerque, where rogue members of our own police force are as liable to shoot an unarmed civilian as give a parking ticket. Or in Chicago, where drive-by shootings routinely claim the lives of young Black children—whose faces rarely make it to a national newscast. In Paris, where pickpockets can become violent, or Madrid where a family member who was stopped at a red light believed a passerby who told him he had a flat tire and before he knew what had happened he’d been cleaned out of everything he had.

Mexico’s violence is endemic and tragic. But so, too, its millennial cultures flourish, its cities are as architecturally exciting and its landscape as varied and beautiful as anywhere in the world.

On a recent visit to Mexico City I felt, more than on any previous trip, how thin the membranes are that separate its layers of astonishing cultures. In the metropolis of 26 million, any street corner may reveal the stones of ancient civilization. Superimposed upon those stones, colonial churches and other buildings speak of the time when Spain’s influence was at its height. And contemporary Mexico doesn’t lag far behind: everywhere magnificent modern architecture, conceived by both native and foreign artists, claims its space—sometimes successfully housing relics from previous periods, as in the case of the massive Museum of Anthropology and History. All this, interspersed by more open spaces than any other city its size: parks, fountains, and greenery wherever one looks.

Like Mexico’s cultural richness, its violence too has its history. A particularly dramatic moment in that history is present in my own memory: the Díaz Ordaz administration’s brutal repression of the country’s 1968 Student Movement. It’s been more than 46 years now, but those of us who were there can still smell the blood and smoke, still know the particular texture of absence when someone we loved was disappeared.

Nineteen sixty-eight was a year in which young people protested injustice globally. Columbia University in New York. What came to be known as The Paris Spring (precursor, perhaps, to the Arab Spring and other rebellions so many years later). In Mexico, a July 26th student march in support of the Cuban revolution was brutally attacked. This was when the Army, wielding a bazooka, destroyed the high school door. Movement demands were for university autonomy, governmental transparency, an end to single-party rule, and other ills. Students took the lead, but workers and farmers soon joined them, making for a powerful struggle.

Mexico was preparing to host the Summer Olympics. A great deal of money had been spent on new sports facilities and an Olympic City where the world’s athletes would be lodged. Private homes joined hotels in advertising accommodations. On September 18th a long line of tanks rolled down Avenida Universidad, breaching a great university’s autonomy. The government feared the loss of its investment. On October 2nd a peaceful demonstration in the Plaza of Three Cultures (one of those spots where an Aztec ruin and a colonial church share space with high-rise apartment blocks) was attacked by Army and paramilitary forces for close to five hours. The event is known as the massacre at Tlatelolco, the name of the tri-cultural site.

I lived in Mexico in 1968. I was in my early thirties and, like most of my contemporaries, participated in the Movement. The night of the massacre at Tlatelolco produced a “before” and “after” in my experience. Before October 2nd I could not have imagined that a self-proclaimed democratic government would murder its own children. On October 2nd I lost my innocence. The years to come provided ample evidence of what the powerful will do in order to retain their control.

Needless to say, the Mexican Olympics took place as planned.

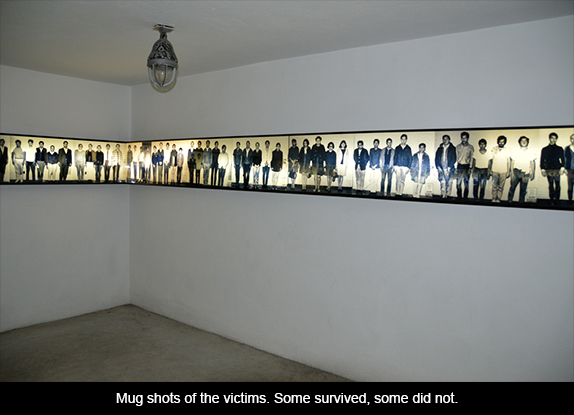

After 1968, I remained in Mexico for a year. But the repression against those who had taken part in the Movement prevented us from leading secure lives. The official death tally at Tlatelolco had been 28, but hundreds disappeared, never to be seen again. The prisons were full, not only of Movement leaders but also of many uninvolved, who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Artists and intellectuals had taken an active role. Many of them were forced into exile. My family and I eventually had to leave the country, a story I have told in detail elsewhere.

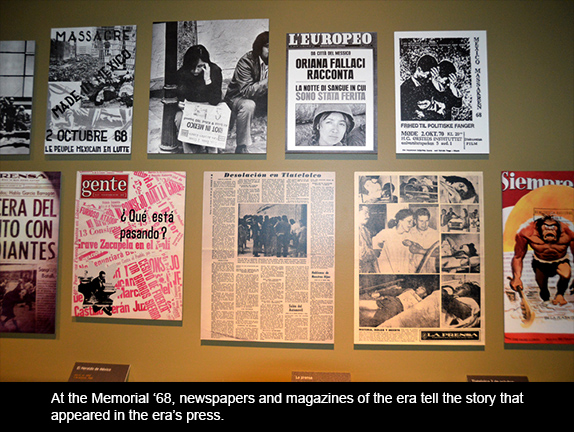

For decades information and newsreel footage about what had happened that night was suppressed. On Tlatelolco’s thirtieth anniversary, in 1998, the archives were opened and a great deal of material made available. This produced a spate of articles and books. The only book that had appeared shortly after the massacre was Elena Poniatowska’s La noche de Tlatelolco (The Night of Tlatelolco), a compendium of first-person accounts by survivors accompanied by photographs. Poniatowska, a brilliant novelist and social activist, has long been known for her courage.

I thought those archives had remained accessible. But on this visit I learned that several years after they’d been opened they were closed once more, and dispersed to a variety of locations, such that it is once again almost impossible to find the damaging documentation. For this reason, I was surprised to hear that a Memorial ‘68 exists, a museum devoted to telling that story of infamy. It is a story in which no one has been charged or convicted. No one has been brought to justice. Which makes it hard to imagine the nation being able to deal with its past.

This is true, I believe, of all nations. Without being willing and able to look its crimes, acknowledge them and make collective decisions about such issues as retribution, amnesty, and how future generations should be taught what was perpetrated, peoples are unable to create a different future. This was true in Nazi Germany and in Cambodia after its Killing Fields. In South Africa, when Apartheid ended, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission set a high standard for this sort of experience.

In many other countries—Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Bosnia, Rwanda, and Peru, among them—the establishment of such commissions have helped heal wounds. Each country’s history and culture has produced variations on how the experience works. In countries such as the United States, where crimes against humanity have gone unacknowledged, swept under the rug so to speak, we continue to grapple with the trauma of unexplored guilt.

I was eager to see Memorial ‘68. And I had the opportunity to do so one evening when I was in the neighborhood. The Mexican museum is unusual in that its storyline begins several decades before the Movement, with the Cold War years of the 1950s. And it is not restricted to Mexico. Furthermore, it does not end in 1968, but extends to the present so that visitors can have an idea about how the country’s contradictions have unraveled since. I was fortunate to be able to go through the exhibition halls with Esmeralda Reynoso Camacho, the museum’s director.

Esmeralda is about my age. She too took part in the Movement of 1968. Present in Tlatelolco on that fateful night, she was captured and tortured for a week before a series of fortuitous events secured her release. A curator by profession, when she interviewed for the job a few years back she was not aware of the task she was being asked to take on. There are eight different museums in the same building, and she didn’t know which one was seeking a director.

When she learned which job she was being offered, Esmeralda decided she would have to think it over. She wondered if she would be able to endure such close and constant contact with this painful part of her past. She did decide to accept the position, though, and says that, although it was very difficult at first, it has gotten easier.

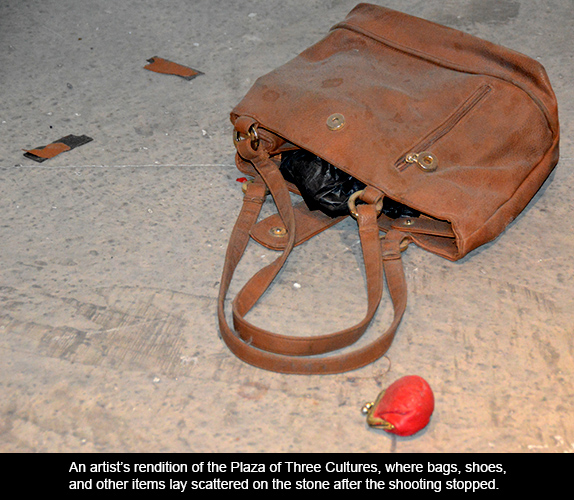

As we moved from images of the Rosenbergs, Martin Luther King, Jr. and others, to those who had taken leadership roles in Mexico, I recognized leaflets and flyers, saw posters and publications of the era. I began to remember faces—older versions of those with whom I had worked, just as I myself have aged. An artist’s reconstruction of scattered bags and shoes, belongings left in the plaza once the shooting stopped, held my attention for quite a while.

Suddenly, there was the famous image of US African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising their black-gloved fists during the Olympic medal ceremony. As the US national anthem played and Smith and Carlos turned to face the flag, they continued their protest to the anthem’s final notes. Both athletes were making a point about South Africa’s presence at the games while apartheid still reigned in that country. The gesture is one of the most overtly political in Olympic history. In retaliation their medals were taken from them, only to be returned many years later.

I remembered how naïve we had been leading up to those Olympics. Those of us in the Movement hoped the visiting athletes would show some sign of supporting our struggle. One or two countries might even refuse to attend the games, we thought. But no. I remembered having tried to sneak into the Olympic Village to distribute material about what was happening in Mexico. We had prepared it in several languages. Of course I never made it through security. Although, Smith and Carlos’ protest was not for us, we claimed it as our own. “We thought they were in solidarity with us,” I said to Esmeralda. “Yes,” she said, “we took what we could get.”

In the final exhibition hall a continuous line of photographs at eye level is the only feature cutting across the gray wall. These are pictures of those who were manhandled, tortured, and worse. The dead looked back at me out of empty eyes: those nameless dead, many of whom remain uncounted.

Visiting Mexico City’s Memorial ‘68 was a moving experience. It reconnected me to a dramatic moment in my past and to old comrades, those who died and those who lived to tell our story, many after prison or exile. And it made me think of my own United States, still waiting for such a museum to honor the thousands of victims of our illegal wars, “extraordinary rendition,” “black sites,” torture sessions euphemistically called “extreme interrogation methods,” and ongoing drone strikes that so often go off course, hitting wedding parties or schools.

Responses to “What Happens When We Don’t Remember: Tlatelolco”