Now, in mid-2014, it seems like everyone is talking about water. If you measured information flow like water, in cubic feet per second, you could say that the discussions have accelerated from Nambe Lake to the Taos Box, or what the Box used to be before the drought. To some extent it’s a natural human tendency--once you learn to see something, you see it everywhere. But psychology isn't totally to blame. We humans are being tossed around inside a point that is in the process of tipping. Water scarcity disrupts lives and humans have to react, creating a world of denial and alarm and uncertainty. They have to figure out the next move in the middle of a game where nature quit following their rules.

Me, I’m getting worn out just trying to keep up with the daily water news. So, when a water gathering was announced in Eldorado, a small community where I live located a few miles from Santa Fe, I decided maybe I should focus on the local, like with food and politics. People around here say “local” like “salud” when you sneeze. At its best, it has advantages for problem-solving. Ideally, it means a group of people share some common experience and a frame of reference in their environment. They make sense to each other in ways that maybe outsiders can’t. And if they’re all having the same problem—maybe for different reasons—there’s motive to cooperate to solve it.

That’s the optimistic scenario. The other possibility is the Hatfield/McCoy syndrome, in which case the problem will sink the locals while they shoot at each other over the details.

The Eldorado event was part of the “Green Cafe” series, held at the “Performance Space” in La Tienda, a sort of shopping center that the owners turned into a configuration of community and commerce. It ran for two and a half hours. It was pretty local, in the good sense of the term. Even the panel of experts was local, consisting of people from local government, the local water district, and a local water company. As moderators, there were two PhD’s in planetary science, both local as well. For the most part, it was a true conversation with the bullshit meter seldom moving off the pin.

Much of the talk was about groundwater. Eldorado depends on wells for its kitchens and bathrooms and plants. Many wells are administered by the local water utility. Many others are private, owned by homeowners for their personal use. “Groundwater” is a slippery concept. When humans think of “water,” it’s usually placid mountain lakes or river rapids or the like, water that you can see and hear and touch. Google “groundwater” and “invisible” together and you’ll see a long list of reports that use the latter term as metaphor for management problems with the former.

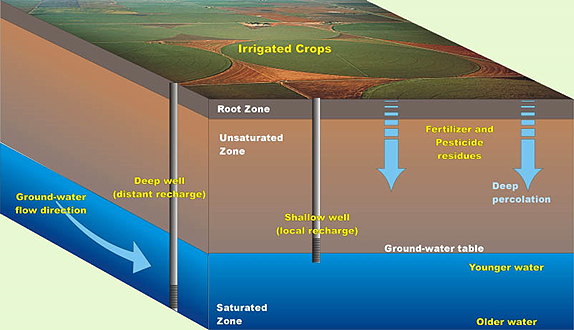

Here’s a picture, not of any actual place, but it gives a first idea to those unfamiliar with the concept, though it’s only one variation on the hydrological theme.

Groundwater, for most of us, is the mysterious hidden gear in the hydrological cycle whose workings we don’t understand. Ironically, this least understood water is also the most abundant source from a human point of view. Of the comparatively small proportion of water on earth that is drinkable—which leaves out oceans and ice—those familiar rivers and lakes are just one percent of freshwater. Almost all the rest is groundwater, this according to NOAA.

And—here’s the kicker—it takes a longer time to accumulate groundwater than it does to take it out and use it. Increasing numbers of humans are drawing groundwater out at a rate faster than it can replenish itself. This strategy, in its most extreme form, is called “aquifer mining,” and the practice is a poster child for unsustainability.

We humans got away with it for a good while. But increasing use and decreasing quantity is creating problems all over the world. Readers have probably seen articles on the example of the famous case of the Ogallala aquifer. It’s happening in Eldorado, too. Well water levels are dropping, we were told at the meeting. Two of the 18 wells on which the Eldorado water district relies are now too low to pump.

There’s more to talk about here than an essay like this can handle. There are many variations on the groundwater theme, the more so when its connection, or lack thereof, to surface water comes into the picture. And the Eldorado news wasn’t all bad. Good work is being done to slow down the draw and make the system—and its consumers—more efficient.

But here’s the thing. We’re still using up the groundwater, some of which is prehistoric and can never be replaced, and some of which is recharged by Mother Nature but more slowly than we humans draw it out. This is the signature problem that won’t go away. Slowing down the draw is just kicking the leaky can down the dusty road.

Here in the Southwest, say the experts, climate change will warm things up, but we will probably also get more rain. As I drove home on my own dusty road, I thought about a comment another local had made at the gathering. Shouldn’t we be ready to take advantage of that increased rainfall, she asked? None of us, neither audience nor expert panelists, put two and two together during the meeting. Why not catch as much rainwater as we can to compensate for the emptying aquifers? Some of it percolates down anyway, true enough, but most will run off and/or evaporate in the hotter air.

We Eldoradrans already have a tradition of putting barrels under our canales to catch the rain pouring off our flat roofs, and some have installed their own storage tanks. The problem with barrels is, heavy storm water shoots off the roof beyond the barrels and then when the amount of rain slows the wind sprays it in many directions. But they work to some extent. Maybe we could dig pits to hold the water, mini reservoirs sort of? We have one in our back yard, probably from the days when Eldorado was a ranch. But then there's the evaporation problem, the more so with the higher temperatures to come. A 2013 article in a New Mexico newspaper said “studies show” that between 8% and 20% of released water from Elephant Butte reservoir is lost, and another says that overall loss is as much as 1/3 of average inflow.

So say it does rain more. How could we gather up and store more of that storm water so that we could use it later? One obvious thing to do is provide incentives for us home-moaners to do a better job of harvesting rainwater—via state tax deduction, county property tax credit, a break on the water bill, something—along with information to help those of us who arrive from the other side of the 100th meridian so we don’t have to reinvent the water wheel. This topic came up a few times at the Eldorado meeting. The enthusiasm of our water leaders at the sight of lost revenue was subdued.

Some years ago I went to an “educational forum” at the UNM Law School called “Aquifer Recharge, Storage & Recovery: Boon or BoonDoggle?” I’d forgotten about it until the Eldorado meeting brought it to mind. “ASR,” they call it for short. A dated essay from 2008 in the e-magazine On The Colorado remains a good brief introduction to the concept and shows that the idea is hardly brand new.

The theory of ASR is simple. To paraphrase the article: Take a depleted aquifer. Pick a recharging method. Locate a water source of suitable quality. Build a conveyance system to deliver and then recover the water. Of course costs are involved here, and it's not clear to me exactly how to best collect a thunderstorm, and one has to consider what the rest of the environment will have to say if that rainwater is diverted. But it sure sounds more sustainable than a strategy of “just keep on pumpin’.”

Here’s a picture by Eddie Moore, for an article by John Fleck in the Albuquerque Journal, from a world-class rainstorm in Eldorado a year ago that hints at the possibilities, obviously not a typical event, but mouth-watering all the same.

Consider another climate change prediction for more frequent extreme weather events: There ought to be a way to get events like this one into an aquifer.

The ASR concept is in play in several places – too many to list here even after a cursory internet search. Interestingly, one place is the Middle Rio Grande. A reader can sample what’s going on from a talk given in 2014 by Amy Ewing and others about ASR projects in Albuquerque, presented at the National Ground Water Association meetings on Hydrology and Water Scarcity in the Rio Grande Basin. Warning: The prose slides into water geek-ese—of course, it’s a professional meeting—but the general story is clear. A successful experiment at Bear Canyon is moving to permanent status and more projects are planned.

So why not have a serious conversation about a long-range plan for ASR in Eldorado? If you can’t beat the wells, then join them.

I’m no expert, though I continue trying to learn enough about water to be an informed citizen. It’s a long hike with a serious elevation gain and no summit in sight. ASR and the groundwater it means to replace is yet another concept to explore for this student of water whose mission seems to be to share what he learned in school today in as clear a fashion as possible. With any luck, it’s useful to readers.

You touch water; you touch everything. El Agua Es Vida. Maybe the theme song should be Ray Charles singing “You’ll Always Miss the Water When the Well Goes Dry.” He’s singing about relationships, but then maybe that’s how we should think of water. Each of us is in a personal relationship with water, though, unlike romantic relationships, humans can’t break up and survive. You can’t sing the blues without water.

(Recharge basin photo by Bill Morrow)

Responses to “Thirsty Locals and Their Declining Wells”