On January 1, 1959, Cuban revolutionaries led by Fidel Castro ousted a dictatorship and claimed their country’s sovereignty. In the United States, the Eisenhower, soon-to-be Kennedy, administration reacted with familiar arrogance. Immediately, covert destabilization strategies as well as all-out military invasion were orchestrated to bring the new government down. US policy, then and since, could not conceive of a nation in its sphere of influence being allowed to follow its chosen path. Millions of people weren’t yet born, or don’t remember this historic event. A little history is in order.

To the United States, prerevolutionary Cuba had been a convenient playground where high-end businessmen could go for a weekend of fun at one of the US Crime Syndicate-owned casinos, spend a few hours with a voluptuous mulata, and drink rum and Coca-Cola oblivious to what life was like for those who serviced their whims. In old Havana, a US Marine had a few too many beers, climbed a statue of José Martí, and urinated on the patriot’s head. Such incidents, harmless jokes in the imperialist mind, to Cubans were symbolic of decades of domination.

For them, their country was a land where a one-crop sugar economy exploited vast numbers of cane cutters who only had work a few months of the year. These people were indebted to the company store and subsisted under miserable living conditions with little access to education and healthcare. Sugar, tobacco and coffee production was in the hands of US companies. Cuba depended as well on US oil and imports of all kinds. The nation’s raw materials and human resources meant huge profit for foreign interests, with a bit trickling down to an ostentatious local oligarchy.

All this got much worse on March 10, 1952, when an ex-president and general named Fulgencio Batista staged a coup and took power. The United States immediately recognized the new government, which it knew would continue to protect its interests. All over the island, young people were looking for ways to take back their country.

A young lawyer named Fidel Castro was able to rally a group that would later emerge as the July 26 Movement. It adopted that name in honor of a failed attack on Moncada Barracks in eastern Cuba in 1953. Many of the rebels were killed in that attack, or tortured to death in its aftermath. The survivors served prison time, were eventually amnestied, and retreated to Mexico to regroup. In 1956, embarking upon an overloaded and risky sea voyage, the secondhand yacht they called Granma departed from the Mexican port of Tuxpan and landed at Las Coloradas beach on Cuba’s eastern coast in the early morning hours of December 2 of that year. Most of the revolutionaries were gunned down upon arrival. Fidel, his brother Raul, Che and a few others made it into the nearby mountains; some have said 12, some only seven. They may have been able to salvage a few weapons. With his decimated troop and these weapons in hand, Fidel famously declared the war won.

Cuba’s revolutionaries, women as well as men, proved brave, strategic, ingenious, and extremely capable. They built an impenetrable stronghold in the Sierra Maestra mountains and a perfectly coordinated underground movement in the cities. In February 1957 they were even able to bring New York Times reporter Herbert Matthews safely into and out of the mountains, where he interviewed Fidel and gave worldwide lie to Batista’s claim that the rebel leader had been killed in the landing.

At first the guerrillas suffered a string of defeats. But they learned from their mistakes and by the end of 1957 were winning battles, capturing military posts, and taking prisoners—whom they treated with a generosity that set them apart from their adversaries. Fidel and a number of other leaders demonstrated an unusual integrity. From a motley group of visionaries—lost, hungry and without enough weapons to go around—and in a surprisingly short period of time, the rebel army grew to thousands: several well-trained columns capable of coming out of the mountains and advancing the length of the country, liberating cities as they went. Just as important, the Cuban people supported their liberators in ways rarely seen before or since.

On January 1, 1959, Batista and his inner circle fled. The July 26 Movement had won the war and began the much harder task of constructing a society that politically, economically, and socially was the antithesis of its predecessor. Had the US observed a hands-off policy, this would have been difficult enough. Given the obstacles it devised to bring the Revolution down, the task became titanic.

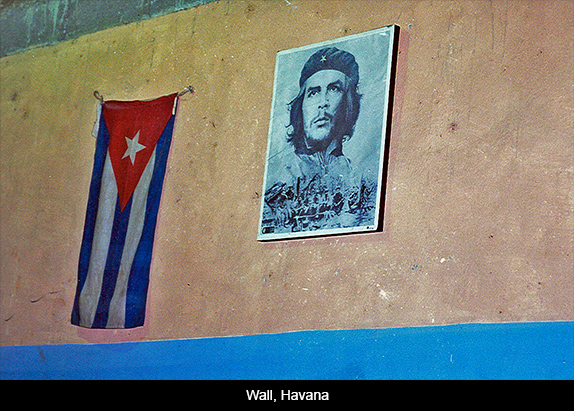

Fidel was the acknowledged leader, admired and beloved in almost every quarter. By February 1959, he was the country’s new prime minister. In April the casinos were closed and Cuba’s pristine beaches opened to the public. In May the first agrarian reform law was enacted. An urban reform law followed. In October a peoples’ militia was established to protect a Revolution already being sabotaged by the United States and disaffected Cubans. Neighborhood groups called Committees to Defend the Revolution (CDRs) were also set up, creating a nationwide web of “people’s eyes and ears” to guard against attack.

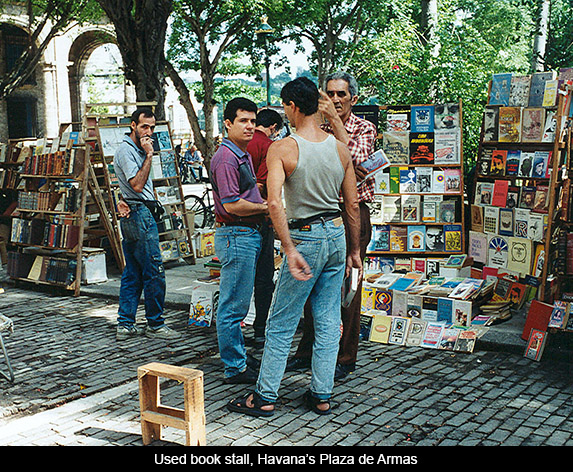

The next few years would see giant advances in the creation of a more just society: the nationalization of sugar mills and foreign oil interests, a literacy campaign that taught almost all Cubans to read and write, the establishment of free and universal healthcare, and an emphasis on putting people to work, building schools, creating daycare centers, and retraining domestic workers and women who had been forced to work in the sex industry so they could use new skills to seek more dignified employment.

It was all too much for a succession of US administrations.

Although new global political configurations, the Cold War, and some important internal errors kept Cuba from the sort of rapid development it envisioned, making people’s basic necessities rather than capitalist profit the priority enabled the Revolution to fulfill dreams of universal healthcare, an educated population, and access to culture and sports. Even today, 55 years later and in its complicated transition to open markets while retaining its principle Socialist gains, what has been maintained is astonishing.

In July 1960, the United States suspended its quota of Cuban sugar; the Soviet Union immediately agreed to buy that sugar at favorable prices. In September of that year Cuba nationalized all US banks. In January 1961, Washington broke diplomatic relations with Havana. The United States increased its program of covert and overt actions against the young Revolution, and in April 1961 launched a full scale military attack called Bay of Pigs in the US and Playa Girón on the island. The Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations expected Cubans to rise up and join the mercenaries. What happened instead was that they defended their Revolution and defeated the invaders in two days. The 1,200 mercenaries captured were later traded for $54 million dollars’ worth of medicine and baby food.

Subsequent years would see the Cuban Revolution developing its unique brand of socialismo en español (socialism in Spanish). From its inception, it saw itself as part of a global struggle. Even as it consolidated its own process, it looked to movements in Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. “Two, three, many Vietnams” became a rallying cry. Cuba’s goals were full independence and the right to design a responsive relationship between the people and their leaders. It contributed a great deal to world Revolution, including the extraordinary generosity of its internationalist contingents of doctors, teachers, soldiers and other experts working in dozens of colonized and underdeveloped countries.

Many who have written about the Cuban Revolution have pointed to this internationalism, this sense of being part of a vast human community, this new consciousness so often mentioned by Ernesto “Che” Guevara and Fidel Castro, as indicative of change that is human as well as political. Cuba became an example for people throughout Latin America and the world; to a great extent it still is. At the same time, its Revolution never stopped aggravating the United States, its powerful neighbor to the north. A series of US presidents vowed to destroy the beautiful experiment, launching an economic blockade, a trade embargo, constant counterrevolutionary propaganda, outright military attack, and hundreds of covert military and sabotage actions aimed at bringing the project to failure.

For many years, the United States was able to prevent Cuba’s natural allies from establishing diplomatic or trade relations with the island. The few nations that defied US threats, such as Mexico and Canada, served as bridges but were unable to make up for lost revenue. Cuba’s adhesion to the Soviet Union saved it from early ruin but also tied it to policies that ultimately proved to be counterproductive. When the socialist bloc imploded in the 1989-90, the Revolution once more found itself alone.

Although all these maneuvers, actions and reactions, have meant additional hardship for the Cuban people, the US’s multi-pronged campaign has not worked. The Cold War ended a quarter century ago, but this remnant of its politics continues: a wooly mammoth in a land of sun and palms. Despite the fact that sectors of the US business community and increasing numbers of lawmakers have pleaded for a different approach, a powerful but aging exile lobby continued to oppose the normalization of relations, holding US Cuba policy hostage. With slight shifts in one direction or another, the United States continued in what can only be described as a bully standoff against a country much smaller and much poorer, that wants nothing more than to be left alone to shape the future it has chosen. A relentless blockade and travel restrictions that were in place until today separated families and attempted to separate ideas.

The Revolution itself has not been perfect; it is made of human beings: brilliant, creative, courageous, and fallible. All it has ever demanded has been its right, as a sovereign state, to make its own decisions, follow its own path. The Cuban Revolution’s great achievements have been near full employment, universal healthcare, free education from daycare through university, and subsidized culture and sports. Important (although as yet inconclusive) strides toward gender and racial equality have been made. Cuba alone among nations has been able to stabilize its HIV/AIDS crisis—no meager list of accomplishments. Although poor, different priorities have made possible a degree of social change of which we can only dream.

Still, the US found it impossible to respect a country with such different priorities. A blockade and trade embargo were initiated in 1962. Although these never achieved their goals of destroying the revolution, administration after administration kept them going. The Helms-Burton Act of 1996 further strengthened anti-Cuban policy by tightening restrictions on other countries intent upon trading with the island.

I and tens of thousands of others have worked half a century to eliminate this unfair blockade. The United States maintains diplomatic and trade relations with dozens of countries with whose systems of government it disagrees: China and Russia, to mention only the most important. Even Vietnam, where we fought and lost our most unpopular war, enjoys a full normalization of relations since 1995. But normal engagement with the tiny island nation of Cuba, just 90 miles from the Florida coast, has seemed impossible. Decades of ill-advised Cold War policy only created more hardship for the Cuban people and prevented the US business community from getting its foot in the door when other countries began investing in Cuban tourism, biomedicine, and other projects. The blockade was a failure from its inception but right-wingers, influenced by a dwindling exile community in Miami, couldn’t stop acting like the proverbial playground bully. It was “get Castro” or else.

President Obama campaigned on the promise, among many others, of normalizing relations with Cuba. When his first term ended with little change, those of us on the front lines of protest thought it might be yet another broken promise. Years of macabre attempts on Fidel’s life, dangerous airplane hijackings, dramatic immigration crises that took their toll on both nations, and lobbying attempts to improve relations that never seemed to get anywhere left the Cuban people exhausted and their supporters here believing we might not see change in our lifetime.

All this changed on December 17, 2014, when Barack Obama in Washington and Raul Castro in Havana announced formal talks aimed at normalizing relations. Earlier in the day Alan Gross, who had served five years of a 15-year sentence on Cuban charges of spying, flew home to the US. The three remaining members of “The Cuban Five,” accused by the US of spying here, were also being released, as well as an unnamed US intelligence agent held in Cuba for almost two decades (he has since been identified as Rolando Sarraff Trujillo, a high-level member of Cuban intelligence who provided the US with important code information). Clearly, unofficial talks had been going on for some time. Their final sessions were facilitated by Canada, and Pope Francis urged both presidents to act now. It will take a while before all the absurd limitations and restrictions are lifted. A reversal of Helms-Burton will require an act of Congress. Still, this is a major step.

President Obama’s announcement echoed some of the familiar complaints about Cuba’s restriction of freedoms and unwillingness to embrace our brand of democracy. But it also sounded a clear break with a failed Cuba policy and made mention of US neocolonialism. The president acknowledged the work of Cuban health personnel fighting the Ebola crisis in West Africa. Although it will take an act of Congress to reverse Helms-Burton, the president can weaken parts of that act, and indicated he is willing to do so.

In a December 17, 2014 opinion piece in The Nation, “Why the US-Cuba Deal Really Is a Victory for the Cuban Revolution,” radical political activist and commentator Tom Hayden succinctly sums up what just happened. I think it is some of the best analysis at this point:

It is quite legitimate for American progressives to criticize various flaws and failures of the Cuban Revolution. But the media and the right are overflowing with such commentary. Only the left can recall, narrate, and applaud the long resistance of tiny Cuba to the northern Goliath […] Despite the U.S. embargo and relentless U.S. subversion, Cuba remains in the upper tier of the United Nations Human Development Index because of its educational and health care achievements. Cuba even leads the international community in the dispatch of medical workers to fight Ebola […] Cuba is celebrated globally because of its military contribution to the defeat of colonialism and apartheid in Angola and Southern Africa […] President Obama has kept his word, despite relentless skepticism from both the left and the mainstream media. He is confounding the mainstream assumption that the Cuban Right has a permanent lock on American foreign policy, especially after the Republican sweep in the November elections […] The embargo is going to be hollowed out from within, with American tourist and investment dollars permitted to flow. With or without Congressional action to lift the 1996 Helms-Burton act, the embargo is being dissolved.

Sources reveal that presidents Obama and Castro spoke on the phone for 45 minutes prior to their respective announcements, surely the longest high-level communication between our nations in half a century. For the first time in decades, Cuba will be allowed to attend the Summit of the Americas, to be held in Panama City in April 2015. Several Latin American countries had recently stated their refusal to be there if Cuba was not invited.

Now that the ice is finally broken, it is up to those of us who care about righting a long-term wrong to pressure our elected officials until full normalization takes place.

Responses to “The United States and Cuba: A Half Century”