Bryce Milligan owns Wings Press in San Antonio, Texas. He is a longtime and extremely successful editor, poet, critic, musician and luthier, educator, book designer, and cultural promoter. In truth, he is one of those rare cultural icons who brings to mind the MacArthur “genius” grant. I will not be surprised if he wins that prestigious honor one of these days; it would be well deserved. As a disclaimer I should say that I am a proud Wings Press author.

In 1996 Milligan spoke to a group of librarians. Among other things, he said:

Until very recently, twentieth century academic literary criticism more often than not described ethnic American literature as parochial, politically driven, and generally as being only a generation or two removed from a living oral tradition—all criticisms aimed, consciously or unconsciously, at somehow negating the validity of such writing as Literature, with a capital L. But the worst criticism, the most devastating review, is no criticism at all, no reviews. Until ‘multiculturalism’ became an accepted tenet of American educational philosophy, most mainstream critics turned a blind eye toward ethnic literature, whether Black, Asian, Native American or Latino/Latina. What amazing works they missed!

Milligan, living in a city that even then was 65% Latino (today a majority of Texans are Latino, foreshadowing US demographics overall), was deeply troubled by the fact that major New York book publishers ignored such rich texts. He was especially concerned with the fate of Latina [women] writers who, since the beginning of the Chicano movement in the mid-1960s, he said, “suffered under the double burden of an academic mainstream only just beginning to see its Anglo male hegemony crumble, and their own machismo-oriented culture.”

Hundreds of Latino books had been published by small presses. Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street had sold 20,000 copies when it was only available from Arte Público in Houston. (It would sell well over a half million copies after it was reissued by Vintage five years later). There was need and there was potential, but the white male (often racist) keepers of the canon couldn’t or didn’t want to acknowledge either. Racially, all they could see were Anglos. In terms of gender, all they could see were men. Anyone outside those two conditions was “other,” and thus irrelevant.

It’s important to name and pay tribute to those small presses. Lacking the corporate networks, promotion, distribution and especially the funding of the major publishers, they pointed the way in terms of recognizing the talent and importance of women and writers of color. Privileging literary value over the bottom line, they led the way—even when few were inclined to follow. Some of these presses were Aunt Lute, Bilingual, Broken Moon, Caracol, Casa Editorial, Curbstone, El Norte, Firebrand, Fuego de Aztlán, Grilled Flowers, Kitchen Table, Linden Lane, M&E Editions, Maize, Mango, Pajarito, Place of Herons, Prickly Pear, Relámpago, South End, Third Woman, Tooth of Time, Tonatiuh, West End, White Pine, and Wings.

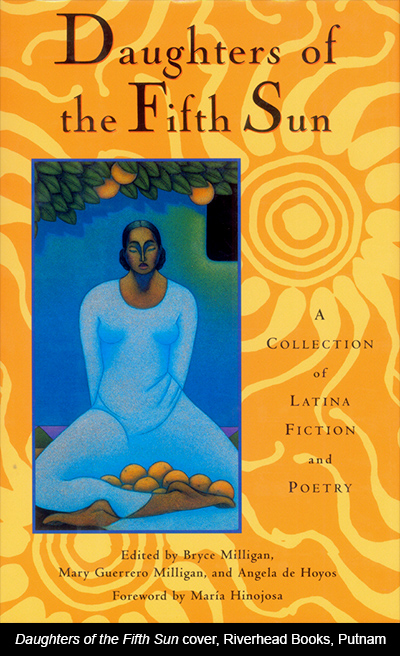

To the librarians Milligan spoke about how, in 1991, he and his wife Mary Guerrero Milligan had sent a prospectus for an anthology of Latina literature to more than 30 publishers on both coasts. Guerrero, herself a librarian, has been particularly involved in trying to introduce inclusivity among the children’s books held in area libraries and taught in Texas schools. The couple’s prospectus received only rejections. Years passed. Then, in 1994 an editor for Harper Collins called. Was the anthology still available? Yes. Harpers made a rather meager offer. By this time Angela De Hoyos had joined the Milligans as a third editor, and NPR reporter María Hinojosa had contributed a forward. Daughters of the Fifth Sun was finally taken by Riverhead Books, at the time a new imprint of Putnam. Tens of thousands of copies have gone out into the world to date, and the book continues to sell well.

Although Cisneros, Ana Castillo, and Julia Alvarez had already joined their male counterparts in putting Latino/Latina authors on the map, Milligan felt an anthology was important to broaden knowledge of the many other important Latinas writing, and also to influence the canon. He remembered Donald Hall’s Contemporary American Poetry of the early 1960s, which had established the canon of contemporary American poets for a whole generation of English majors. Daughters of the Fifth Sun did the same for students of Latina literature, and for everyone who sees that literature as being an important part of American literature as a whole.

Overlooking women is something that has long happened in our society. Tillie Olsen’s groundbreaking 1965 book Silences documented how few American women writers were included in anthologies, taught in university literature classes, published in journals or received foundation grants. Muriel Rukeyser’s civil war novel, Savage Coast, was written in the 1930s but remained unpublished until long after the writer’s death; publishers didn’t believe a war novel could be written by a woman. Although the ratios have improved somewhat, the inequality remains palpable.

This is the real issue: inclusivity vs. rejection of anything that does not conform to white-only, overwhelmingly male, writing. Writing that ignores the many cultures that make up the fabric of our nation. In response to the success of efforts such as Milligan’s, the past decade or so has seen a veritable war against literatures by writers of color, women, members of the GLBTQ communities and anyone else whose identity, experience and expression doesn’t fit the traditional mold. Such literatures may sometimes enjoy momentary interest, as oddities or tokens, but soon revert to their second-class status.

Milligan was the perfect person to take this struggle on. In the early 1980s he created the first Chicano literature class at the University of Texas, San Antonio. From 1983 to 1990 he was the book columnist for the San Antonio Express-News and then the San Antonio Light. Throughout those years he rarely reviewed a bestseller, preferring to concentrate on Chicano/Latino small press and children’s books. He understood the fluidity between literature written on either side of the Mexican/American border, and also their unique differences.

In the United States, books written by Latin Americans have often been considered exotic or in other ways desirable, while those written by their close cousins living here have been disregarded as if the racially determined situations of their authors render them commonplace or second-rate. Milligan’s editor began to get edgy: Why was he giving so much attention to those unknown authors and miniscule presses? What about John Updike’s latest? What about Joyce Carol Oates? What about the New York Times bestseller list? He told his editor that he was reviewing what should be of most interest to the community.

An educator, Milligan always understood that reading begins in the schools. In 1983, he and Mary started a small multicultural book fair at a local alternative school. Two years later this experience morphed into the first annual Texas Small Press Book Fair, and eventually into the Inter-American Book Fair. Bryce took directorship of the latter for the second time in 1994, until its demise in 2001. Over its 15-year run, the fair brought some 700 writers to San Antonio, the majority of them Chicanos and Latin Americans. (The 1998 Fair focused on Native American writers.) In 1996 Milligan launched an annual conference, “Hijas del Quinto Sol,” devoted to Latina literature and identity and co-hosted by the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center and St. Mary’s University. This eventually became the Latina Letters Conference, still held periodically at St. Mary’s.

Bryce tells the story of how he managed to get the San Antonio Public Library to stock Chicano literature:

In the 1980s I was in the habit of attending periodic board meetings to complain about the lack of Spanish language materials and, as time went on, the lack of Chicano literature. They got a new director in 1989, David Leaman, who began to listen to me. Leaman was in charge during the design phase of the “enchilada red” library, and he had assured me that they would include a non-circulating Latino lit research collection. When the library opened in 1995, the collection was not there. I began complaining about this again, both in newspaper articles and at board meetings. In 1997, a board member said publicly that there was “neither demand nor need” for what I was requesting. The mother of Julián and Joaquin Castro, Rosie Castro, an activist from the early Movimiento, was in the room. At the next board meeting she showed up with dozens of high school students who stated their experiences of having to travel to half a dozen libraries to write a single paper on a Chicana/o writer, including Sandra Cisneros. They spoke for hours and hours. A week later, a special board meeting decided to create the collection—which is now one of the gems of the library—and to increase Chicano holdings in all the branches. The next year, 1998, the new director, June García, awarded me their annual Library Champion award for outstanding service.

Milligan was also willing to share with me briefly the history of how he was able to get the University of Texas at San Antonio’s campus to acquire a Chicano literature collection. The school was planning to offer a PhD program in Culture, Literacy and Language, with a concentration in Mexican American Studies. It had strong holdings in Latin American literature, but little by Chicano authors:

I pointed this out to the library director at the time, Mike Kelly (deceased), and we began discussing the purchase of my Latino/Latina collection. The collection consisted of some 2,000 volumes plus many manuscripts and much correspondence. It was appraised by John R. Payne of Austin (he did Nixon’s papers too!) The university purchased the collection in 2003. This formed the basis of the UTSA research collection in Chicano lit.

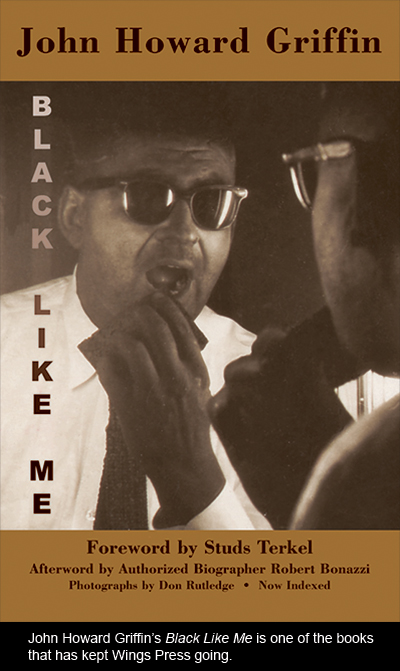

It is through Milligan’s longtime work with Wing’s Press, though, that he has perhaps contributed most to an exciting diversity in literature. The press was founded in 1975, and Bryce took it over twenty years later. Since then he has published 192 titles, 165 of which are still in print. Of the press’s 111 currently active authors, 42.3 percent are Anglo, 56.8 percent non-Anglo, and 54 percent are women. Of the books published in 2013 and 2014, 42 percent are by men, 58 percent by women, and half of the women are Latina. As of the end of 2014, approximately 80% of the press’s anthology contributors have been women. Although Bryce says they do not collect sexual orientation stats, Wings has won or placed in both gay and lesbian book award contests at the national level.

Mary Guerrero Milligan has concentrated, meanwhile, on literature for the younger set, working tirelessly to make it more inclusive. As a librarian, she has held several positions with the Texas Library Association, and is committed to promoting diversity in literature for children and young adults.

Many people around the country of course are dedicated to diversity in literature. For every one of them, though, it seems there are school boards, publishers, and critics—sometimes motivated by a Christian fundamentalist ideology, sometimes simply by smug ignorance—who push back against freedom of expression. They wage this war on many fronts. They are afraid of young people of color, especially, being empowered by reading about their own histories and cultures, having access to past figures and mentors who can inspire their emerging identities. Prevent such readers from recognizing themselves in what they read, and you will be able to control them more effectively. Real educators, independent booksellers, small presses, and librarians, on the other hand, support a broad multiculturalism.

Here in New Mexico we had a taste of this war in 1997, when Nadine and Patsy Cordova, two sisters from the small town of Vaughn, were first suspended and then fired from their longtime teaching positions because they designed a curriculum that included Chicano history and literature—what has come to be known as Chicano Studies. The Cordova sisters fought for their rights. The American Civil Liberties Union took their case, and won it in 1998. Damages included $450,000 from the school district and an additional $70,000 from the school board’s attorney. Both sisters moved to Albuquerque, where one continued to teach in the public schools and the other was hired by the University of New Mexico. This case was considered a victory for freedom of expression by everyone familiar with it.

This of course wasn’t New Mexico’s first brush with intolerance, nor would it be its last. The narrow-minded religious right doesn’t give up easily. Efforts to introduce creationism and so-called intelligent design into school curriculum throughout the country increased noticeably at the beginning of the 21st century. In Alabama, references to the Middle Passage and our country’s sad chapter of slavery were eliminated or downplayed in textbooks at all levels. When a nation curtails its historic memory it is destined to repeat its errors. In Texas, too, such distortions were introduced into school texts. Texas and California possess an influence beyond those states’ borders; their large populations make them trendsetters.

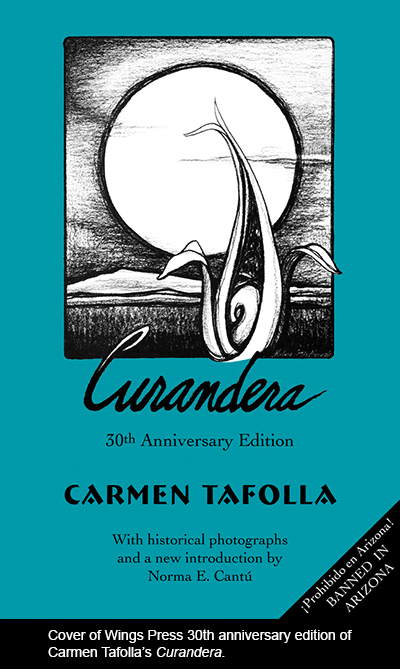

In October of 2012, the Tucson, Arizona Unified School District (TUSD) launched a two-pronged assault on freedom of expression and literatures that reflect ethnic and progressive points of view. The District closed down all Mexican American Studies programs and went so far as to ban books, removing more than 100 titles from classrooms while the classes were in session. Arizona students might as well have been in Hitler’s Germany, when banning and burning books was routine.

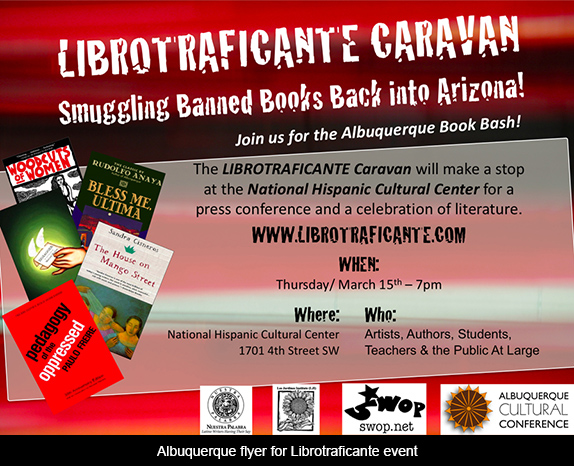

Among the important books banned in Arizona were: Critical Race Theory by Richard Delgado, 500 Years of Chicano History in Pictures edited by Elizabeth Martínez, Message to AZTLAN by Rodolfo Corky Gonzales, Chicano! The History of the Mexican Civil Rights Movement by Arturo Rosales, Occupied America: A History of Chicanos by Rodolfo Acuña, Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire, and Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years by Bill Bigelow. Novels and poetry collections by Sandra Cisneros, Luis Alberto Urrea, Rudy Anaya, and Leslie Marmon Silko were also on the banned list. What the enforcers of this fascist ruling were trying to accomplish is obvious. They wanted to prevent students of color from knowing their history, inhabiting their identities, and exploring dissent as an option in the face of ongoing injustices.

This time we—overlapping communities of artists and social activists—weren’t going to take the affront without a fight. Chicano activists Tony Díaz, Dagoberto Gilb and others organized a caravan in Houston that made its way through a series of cities picking up writers and artists as it moved west. In each place local poets and writers staged benefit readings that raised money to buy copies of the banned books. Here in Albuquerque we filled the National Hispanic Cultural Center (NHCC)’s largest auditorium for a magna reading. Hundreds of copies of the banned titles were distributed on the streets of Tucson, and copies also now form the core of free libraries along the way.

In Tucson itself, students and others got together to try to reverse the ignominious school district decisions. University of Arizona professor Roberto Rodríguez was one of the primary organizers, drawing people through his concept of “we are our other we” to recognize their roots and fight for free expression of those roots. Unfortunately, the destruction of study programs and the burning of books are only two manifestations of Arizona’s anti-immigrant, anti-Latino policy. Racial profiling in that state is at an all-time high, people are stopped in traffic or on the streets merely because of the color of their skin, and thousands of undocumented families have come east to New Mexico to escape the constant humiliation and danger they face in Arizona.

Continued activism has not yet managed to change Arizona’s retrograde law. The struggle continues.

Many writers of color, such as Alice Walker, Piri Thomas, Nikki Giovanni, Simon Ortíz, Gary Soto, Luis Rodríguez, Luci Tapahonso, Joy Harjo, Carmen Tafolla, Ana Castillo, Amy Tan, Julia Alvarez, Luis Alberto Urea, Sonia Sánchez, and Sandra Cisneros have entered the mainstream. Gloria Anzaldúa has changed our understanding of the borderland, conceptually and linguistically. Audre Lorde’s influence goes far beyond the original readership of her poems and essays. Newer names, such as Renato Rosaldo, Janice Gould, and Richard Vargas are emerging all the time.

Bryce Milligan is a brilliant and tireless cultural promoter, as well as a creative personality in his own right. His Wings Press has a compelling record in the ongoing publication of relevant literature—including poetry, history, essay, novels and criticism. As I said at the beginning of this article, if there is justice to be had, a MacArthur grant should one day come his way.

Responses to “The Role of Small Presses in Fortifying Literature”