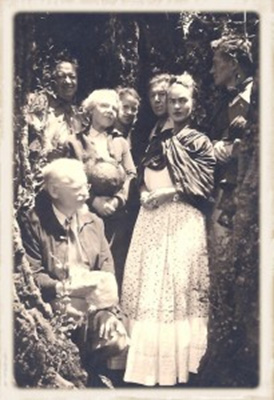

(Van Heijenoort, far right, with (L to R) Trotsky; Diego Rivera; Natalya Trotsky; Reba Hansen; André Breton, surrealist writer and theoretician; Frida Kahlo. Coyoacán, Mexico. ©Laure van Heijenoort, Used with permission.)

As the global capitalist system tumbled over a cliff in the late 1920s, French teenager Jean van Heijenoort took the first steps toward a two-decade career as a professional revolutionary, the crucial part of it at Leon Trotsky’s side. More than 100 years after van Heijenoort was born in 1912, capitalism is in crisis again. But people of his caliber aren’t dedicating their lives to overthrow it.

When Jean heeded the call of revolutionary socialism, he was one of millions who were certain that capitalism was on its last legs. Apart from the evidence staring them in the face, a large body of serious theorizing said the system’s collapse was inevitable. The Soviet Union seemed to offer a plausible alternative. Plausible under some conditions. For Trotsky and his followers in the 1930s, the conditions included ending Stalin’s dictatorship, halting the liquidation of the revolutionary class of 1917, as well as the murderous forced collectivization of agriculture.

Jean eventually realized that the supposedly inevitable proleterian revolution wasn’t, in fact, destined to happen. He also came to accept that Trotsky, among others, laid the foundations of Soviet totalitarianism. In the 1950s, though he had renounced political activity, he signed on to help the U.S. government prosecute one of the most sinister of the corps of Soviet agents deployed against Trotsky and his circle. Jean and others like him wound up on the U.S. side in the Cold War in large part because the other side had been trying to kill them.

(Van Heijenoort, second from right; Loretta “Bunny” Guyer, his future wife, at far right. ©Laure van Heijenoort, used with permission.)

This dimension of Cold War history is pretty much forgotten. Periodic bouts of nostalgia about the 1940s and ‘50s still typically focus on targets of anti-Communist investigation – celebrating and occasionally condemning the work of pro-Soviet artists and entertainers (Jean shared his centennial with one of them, Woody Guthrie). Jean himself appeared as a major figure, “Van,” – as Trotsky and many others did call him – in The Lacuna, a novel by Barbara Kingsolver. The book’s plot unfolds partly in Trotsky’s final refuge in Mexico – a setting portrayed much more accurately in Hayden Herrera’s definitive biography of Frida Kahlo, for which Jean was a major source (the film version includes Jean as a character, albeit briefly). Kingsolver, for her part, foolishly and ignorantly conflates the experiences of ex-Trotskyists and ex-Stalinists during the McCarthy years.

Members of those groups didn’t, in fact, have any more in common during that period than they’d had in the years leading up to it. By 1948, Jean wrote in his 1978 memoir “the full extent of Stalin’s universe of concentration camps became known at least to those who did not wish to close their eyes or stop their ears.”

Responses to “The real “Van””