The National Hispanic Cultural Center, in its old Works Progress Administration (WPA) building, has been exhibiting a collection of WPA art made in New Mexico since October 5, 2013 (the show will close on March 1, 2014). According to Carlos Vásquez, the Center’s Director of History and Literary Arts, the pieces on exhibit were chosen from a vast number “because they depict how the artists saw our mountains, sky, canyons and people. We also wanted to represent images from around the state. And, because the focus is so often on male artists, we wanted to include as many images as possible by women.”

Vásquez, who says he was raised by a single mother, and that at NHCC his boss, his boss’s boss, and on up are all women, says a little-known fact about the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps in New Mexico is that there were not only camps of men. “In Lincoln county there was a camp where 250 women lived and worked. Just before it opened the Army removed the stoves. The women went to nearby towns, managed to obtain enough parts to put two full stoves together, and that’s what they cooked on throughout the time they were there. Food was good, and it had the reputation of being the most beautiful camp. Many of the residents—women as well as men—remained in our state.”

Upon his election in 1932, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had to confront the Great Depression (the 1929 collapse of the banking and financial sectors). His solution, among others, was the New Deal. This was a broad collection of programs meant to address the serious problems of unemployment, hunger, abandoned infrastructure, and hopelessness that were sweeping the country. This wasn’t about saving banks that were “too big to fail,” but about putting ordinary men and women to work, giving them a place to live and a modest salary, keeping them from starvation and allowing them the pride and creativity of helping to rebuild a battered nation. An informative catalog produced by NHCC tell us “Here in New Mexico, Governor Clyde Tingley and US Senator Denis Chávez saw to it that the State receive an inordinate amount, per capita, of New Deal programs.” It must have been comforting to live in a time when our president cared about working people, and we had a governor who cared about the State.

The New Deal sought relief for the needy, economic recovery, and reform of US American capitalism. It included programs, many of which became ongoing agencies, that helped farmers, conserved soil, laid sewer systems, built roads and other infrastructure, provided housing for the homeless, repaired schools, and created lasting art. NHCC’s exhibit displays some of the New Mexico art from this period. It is fascinating, covering the walls of most of the halls throughout the beautiful building. These pieces will only be up for another couple of weeks, so if you haven’t been there yet it is definitely worth a visit. Attending a lecture by Dyanna Taylor on Saturday afternoon, February 8th, I had a chance to view some of this art. The WPA Building’s Ortega Hall was overflowing with an appreciative audience that filled every seat and stood several deep along the walls.

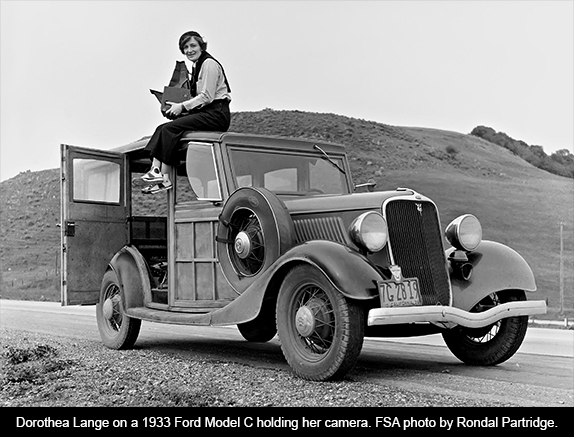

For the past five months the NHCC has featured not only this exhibit but also other programs on the New Deal. It opened the show with a symposium and followed up with lectures and panel discussions. Dyanna Taylor’s talk, accompanied by stills and footage from her forthcoming film Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning, to be released on Labor Day, 2015, was the experience that sparked this commentary. Although I have long loved and admired Lange’s work, I was surprised to learn about the photographer’s New Mexico connections.

Dyanna Taylor, a Santa Fe resident, is Dorothea Lange’s granddaughter and deeply influenced by Lange’s sensibility. An award-winning filmmaker in her own right, she says she was around her famous grandmother until she was 14 years of age. The first image in her evocative Power Point was a faded black and white of her own outstretched child’s hand holding a few stones and leaves. As a photograph it is quite ordinary, but came to life when Taylor said she held the found objects out for her grandmother’s approval and Lange snapped the picture. As soon as she did so, she asked her granddaughter: “But do you see it?” It was, Taylor said, her first lesson in what seeing is.

What followed was an overview of the great photographer’s life and work, culminating in moments from the very end of her life when she was reviewing years of archived negatives with an eye to preparing the first exhibition ever given to a woman photographer at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Sadly, she died three months before the show opened. The bulk of Lange’s photography emerged from her travels and documentation during the New Deal.

Following the Great Recession of 2008, many of us believed the country could have benefited from another New Deal. Three lean years later, upcoming electoral candidates would do well to demand this and others of the solutions Roosevelt applied to the earlier era of environmental degradation (the Dust Bowl), lost jobs, a middle class sinking into poverty and a working class growing poorer, larger and more hopeless. Today the income disparity between rich and poor in the United States is even greater than it was at the beginning of the Great Depression.

But what surprised me, as I say, was the intimate connection Lange had with our impoverished state of New Mexico. Today we are at the bottom of the national list in terms of poverty, child hunger, health care, and education. As our governor systematically plays the greed game with our resources, selling some off to neighboring states and destroying others in line with her plans for personal power and enrichment, I think with nostalgia of the 1930s. Back then we struggled as well, but Governor Tingley had our best interests at heart.

Dorothea Lange did much of her most important work during and just after the Great Depression. Much of it reflects how the Depression shaped people’s lives: their resilience as well as their despair. She had several muses, powerful influences on her art. One was a bout of childhood polio that left her with a limp but gave her added incentive. Another, undoubtedly, was the camera itself. Her first husband, the artist Maynard Dixon, also played an important role. He introduced her to the Southwest, and encouraged her to develop her commitment, talent for composition, and ability to see and document what she saw. Yet, in an arrangement painfully typical of the gender differences that prevailed at the time, when they lived in Taos he painted while she took care of their two boys!

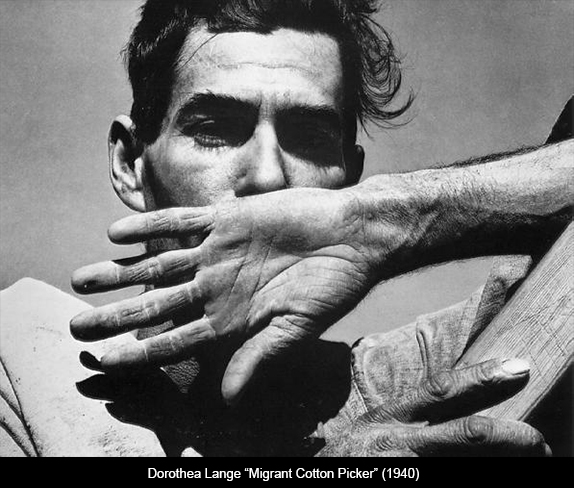

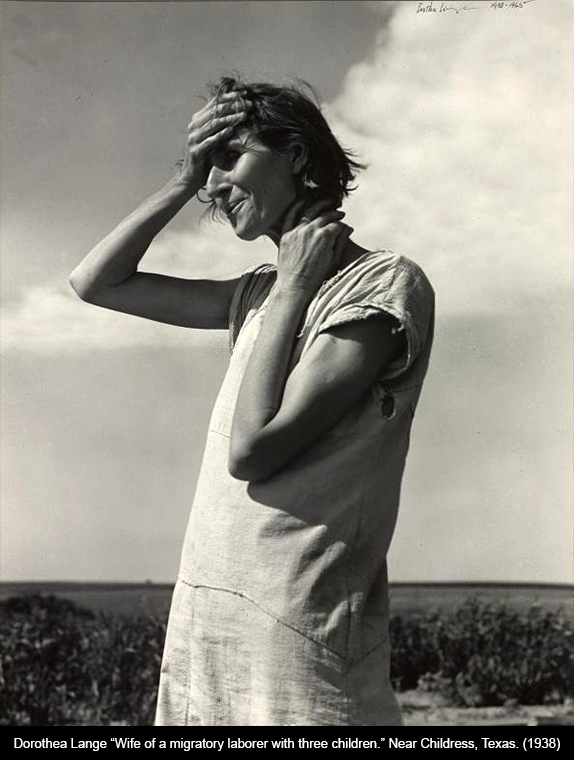

Another great influence was her second husband, Paul Taylor. He was Dyanna Taylor’s grandfather. A radical economist, he studied labor in California, including the work being done by immigrant communities from the Philippines, India, Pakistan and Mexico. He introduced Lange to the terrible problems plaguing the country, problems she brought to light with her astonishing eye. Taylor worked for the government, writing about migrant workers, poor dirt farmers and others for whom the American dream had become a nightmare. He recognized Lange’s great talent and took her with him on many of his study trips. With him she photographed sharecroppers, destitute families, and others. She never called herself an artist, but preferred to say she was a craftsperson. Her gender, small stature, limp, and genuine interest in the human condition allowed her to go where others wouldn’t or didn’t; and to gain the trust of men and women who would become iconic images in the history of photography.

Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor married at the Albuquerque, New Mexico courthouse in 1935. From 1935 to 1938 she worked for The Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration), photographing the Dust Bowl (yes, it also invaded New Mexico) and the misery caused by that devastating climate phenomenon.

Dyanna Taylor’s Power Point featured at least three New Mexican images: a Dust Bowl scene, a warm interior in Bosque Farms, and a Santa Fe service station with a sign showing the breakdown of profit in a 20-1/2 cent gallon of gas (what part of the cost of each gallon went to the federal government, state government, distributor and the station’s owner).

Lange said she wanted to photograph “what is really there, what it looks and feels like.” We saw a magnificent portrait of six sharecroppers standing in a row, each an individual picture of strength and integrity and the group shot one that few photographers could have achieved. Dyanna Taylor also showed us the same image with the last man on the right cut off. Photoshop was decades into the future, but editors still tried to shape photographs to say what they wanted them to say. Lange’s work resisted this to an extraordinary extent.

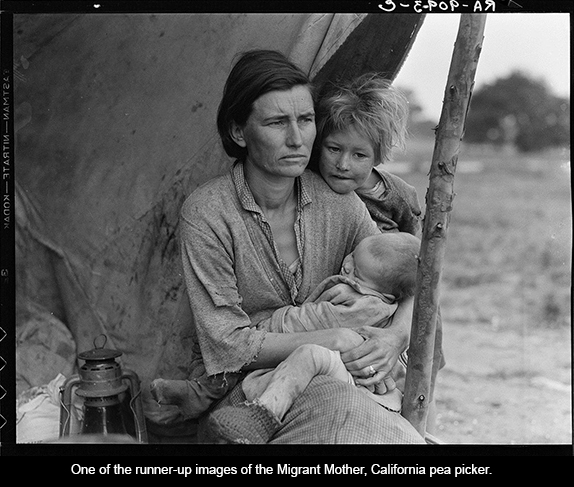

Which brings us to what is perhaps Lange’s most iconic image, “The Migrant Mother.” The negative sheet shows the five pictures Lange shot as she approached the mother and her children sitting beneath a makeshift shelter at a pea harvesting camp she had almost passed by. As she comes closer, her camera becomes more focused on the mother. Then there is a sixth image, and a seventh. It is this last that made history. It became a hallmark of Lange’s work, traveled round the world, and was eventually reproduced on a 32-cent US postage stamp. Proponents of several causes have altered the Migrant Mother image in different ways. Her face was even replaced by an African American woman’s at one point, and more recently “beautified” by contemporary artist Kathy Grove.

![]()

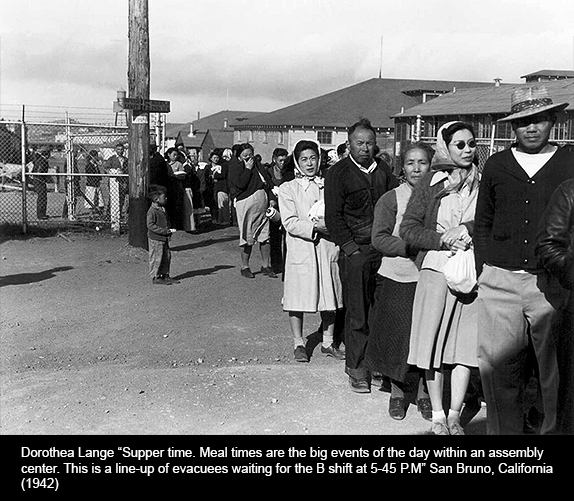

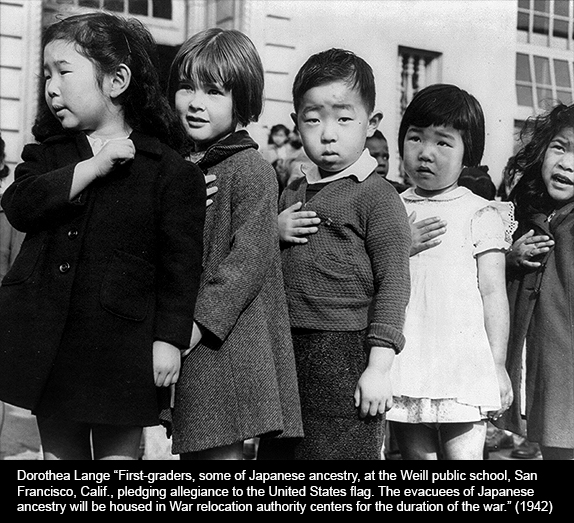

Among Dorothea Lange’s most important documentary work is that which she did on our country’s disgraceful roundup, displacement and internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. She photographed them being forced to leave their homes with a single small suitcase each, boarding the trains that would take them to the concentration camps, and their life in those camps. Despite the fact that she was often accompanied by a “minder” and her photographs were censored by the government and “disappeared” in their entirety for many years, they remain mirrors of injustice and resistance. Lang’s work at Manzanar Camp in California is particularly moving. Confronted by the extreme racism and cruelty inherent in the imprisonment of loyal Japanese-Americans, Lange became physically ill. What she described back then as “a bellyache,” eventually became the esophageal cancer that would kill her twenty years later.

Extreme economic disparity, such as we have in the United States today, breeds inequalities of all kinds, and often the sort of racial profiling that during World War II took the form of barbaric treatment of our Japanese American neighbors. Bizarre incidents have been recorded, such as a Japanese-American soldier being granted leave from the war in order to help his family move to a camp. We are fond of vowing “never again,” and indeed the travesties that threaten us today would most likely be different from those that shamed us back then. But injustice is always accompanied by discrimination because some group of people is always at the bottom of the social ladder.

Today we might liken whistleblowers such as Chelsea Manning, Aaron Swarz and Edward Snowden to documentarians Lange, Lewis Hine and Walker Evans; except that the latter brought the added power of their art to bear on the situations they exposed. Still, Dorothea Lange thought of art in a utilitarian way. Toward the end of her life she said: “Art is a byproduct of an act of total attention.”

We, each of us in our field, need to be paying attention now.

Responses to “The New Deal, New Mexico and Dorothea Lange”