Who is the good mother? From the earliest representations of women-- Paleolithic figurines with wildly inflated reproductive organs – through modern mothers Facebooking their cleanest, happiest family photos, she is a creation mixed with history, culture and pure imagination. The good mother has features we all recognize—her supernatural patience, unwavering attention and empathy, submission to the needs of others, and an expectation to have her own value measured heavily by the outcomes of her offspring. Yet for each of us she has special features endowed to the good mother by our own experiences, values and mythologies. The good mother of my mythology smells like gardenias.

The problem with the good mother is that she is a myth that many women rely heavily upon as the role model for their real, dirty, wonderful but emotionally turbulent motherhoods. In an ever more isolated, nuclear culture without the communal, familial exposure to motherhood from which women traditionally gathered knowledge and support, images of motherhood are increasingly replaced by fictional representations. These images come from advertising, social media, and cultural norms. At the same time, a culture of competitive childrearing has risen in which the race to be the best mother begins at conception and lasts through every meal, every sport and music lesson, every school choice, every family photo.

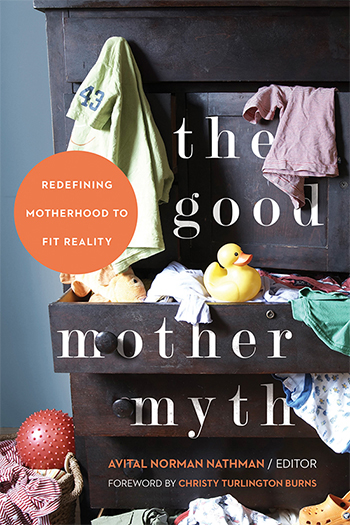

When I first considered submitting an essay to the book The Good Mother Myth: Redefining Motherhood to Fit Reality, I mused that I likely did not have anything written that fit closely enough with the theme of the book. However, as I read through years of my writing about motherhood, I realized that there was hardly a line in which the good mother was not present, guiding either my choice to emulate her or to refuse her. Both adherence and rejection to the good mother have their prices. In the book, contributor Candace Walsh recalls a diary entry she made at the age of 17, listing her criteria for herself as a future mother:

When I become a mother... I will do everything in my power to give my children a normal, stable life. I won’t marry the wrong man like my mother did. I will marry someone who will be a wonderful father. My kids will have nice clothes and shoes, and will never worry about the electric being shut off. We’ll drive a reliable car, nothing fancy, just not an old clunker. Otherwise, I shouldn’t have children. It’s just not responsible.

However, later she finds that she is unable to completely fill the image she had set up for herself as a mother. In concentrating so fully on finding a responsible and normal life for her kids, she sacrifices the joys of a more authentic, if messy, life. Of her married life that fulfilled her own motherhood ideal, she writes, “Unfortunately, we were still living in reaction to our childhoods—making choices based on what we didn’t want, instead of teasing out what we did.”

So often the perception of failing as a mother is hinged upon choosing the self over the idealized selflessness. In my own essay, I struggle with competing feelings of raising my son in our church while having a deep uncertainty about my own beliefs:

If he follows down the Christian road, he will know the idealized mothers of the Bible, the women on whom Western, Christian models of feminine perfection were built. These are the women who greet God’s requests with thy will be done. My existential work with Jonah could not be more unlike their ecstatic suspension; my every word is tainted with self-interest. I profess the intention of raising him with an open heart and mind, but truthfully I am asking him to understand belief as I do, my will be done.

Ultimately, it is not a heavenly morality that imparts guilt in this reflection; it is the culturally-celebrated criteria that the good mother subdues her own wants and needs for the stability and prosperity of the family. Most of the time I even agree; it is a constant practice of compromise and cooperation to even live with people, much less raise them. But when the self feels directly threatened by selflessness, good mother mythology chooses selflessness every time.

As we deconstruct the good mother myth, we have to ask ourselves: if a person is enacting self-censorship to fulfill an idealized, nearly supernatural role, what is such a role worth to that person? We cannot be both ourselves and the good mother; total devotion to that role is a displacement of the self. And yet for many of us, the good mother is who we call on in our dark moments to remind us who we wanted to be for our children. It is a balancing act, along with the rest of motherhood, to be cognizant of her guilting, expectation-laden presence while taking from her what strengthens us.

Editor’s note: This Saturday, March 8th, at Collected Works bookstore in Santa Fe, Victoria Rodrigues and Candace Walsh, both contributors to The Good Mother Myth: Redefining Motherhood to Fit Reality, will read from the book, discuss writing about motherhood and the challenges of being a writer and a mother, and lead writing exercises designed around this theme. The event starts at 2pm.

Responses to “The Myth of the Good Mother”