It’s one of the most important days in the life of Yeira Rubi Beltrán. Her quinceañera. She lives on the west side of Juárez with her brother, Hector and her grandmother, Elvira Romero in a shack with little protection against the rain and wind. To survive, they’ve often had to find scrap metal to sell along the highway. “They’ve suffered a great deal,” Elvira says.

Her father, also named Hector, lives in central Juárez but provides no support. The mother? No one knows where she is. Nonetheless, this is a day Yeira has been anticipating for years.

I first met Yeira and Hector in March, 2011. Their grandmother, Elvira was the cook at the nearby mental asylum, Vision in Action that I visit every month. On that first visit, Yeira and Hector were in the main patio, talking and laughing with two patients named Becky and Spiderman. I thought to myself, “This is bizarre. Are they patients? They seem so young.”

Then I learned that Elvira would bring them to the asylum on weekends because it was too dangerous where she lived to leave them home alone. I also learned that Yeira was exactly two weeks younger than my granddaughter, Audrey who lives in Denver. Their lives are as different as if one lived on the moon and the other on Mars. Perhaps this is why I’ve tried to help.

First, I gave them writing assignments. Write your life history for me. Or your hopes for the future. Then I asked them to help me with photography projects within the asylum. For example, they’d write down the names, dates of birth and family histories of patients I photographed. They write well, are smart, get good grades and want to succeed. And they’re fearless. One weekend, for example, Yeira interviewed a man named Arón Carrasco. He is a former killer or “sicario”, has murdered at least fifteen people and spent close to twenty years in various Mexican prisons. I was horrified when I found out that she had done this on her own. “Weren’t you afraid?” I asked her. “No,” she said. “It didn’t bother me but he was crying.”

In return, I’ve been helping with clothing, shoes and other expenses. I offered to help them continue music lessons but they had no transportation to get to the classes. In short, they lack every one of the conveniences that we take for granted – hopping in your car to run an errand, having a phone that works etc.

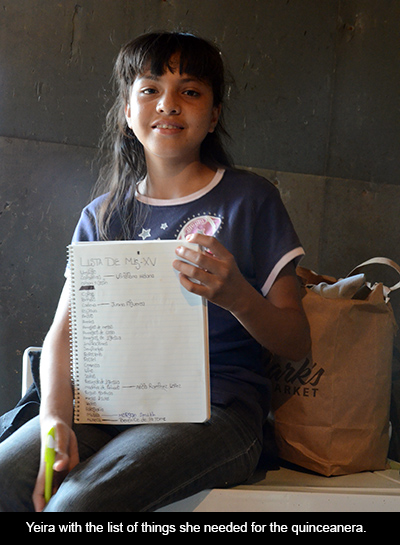

Then last September Yeira produced a list of 28 things for which she needed sponsors or “padrinos.” This was for her quinceañera, something I quickly realized was extraordinarily important to her. I was skeptical - how can one event change a life that is so mired in poverty- but I immediately agreed to help, not really knowing what I was getting into.

The first step was a tour of their barrio and “interviews “ with various musicians. Eventually, I signed a contract with a young DJ named Gabriel Morales. Then I drove them to a dress shop on Calle Lerdo in downtown Juárez called La Mágica de Tus Sueños, (The Magic of Your Dreams) saving them countless of hours traveling there by bus. This led to two additional trips plus the recognition that I would be paying for the dress and other expenses in addition to the music. It was silly of me to have thought that neighbors and friends in this poverty stricken barrio would be able to help much and I accepted this role as the main “padrino.”

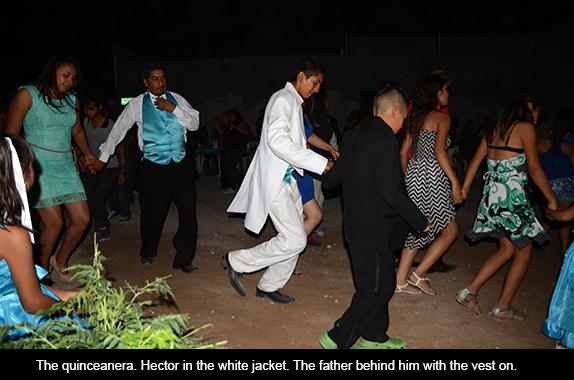

Finally Saturday arrived. At five thirty PM Saturday, Yeira left her house in the beautiful dress. Hector followed, very mature looking in a white jacket. They went in Pastor Galván’s red car to a church called El Banco de Misericordia where musicians from the church were waiting. After several deafening hymns, Galván preached a tough message. In a city as violent as Juárez how can you excel, how can you realize your dreams? Yeira and Hector both want careers in the medical field; how can they achieve these dreams?

In the audience was a serious looking man in a suit and tie. This was Hector Beltrán, their father. It was a bittersweet surprise because he almost never comes to see them. He stayed to dance afterwards but did nothing to help with the cost of the quinceañera.

Then we returned to Elvira’s house. On the dirt street in front of it, they had set up chairs and tables. Elvira and neighbors were cooking. The very impressive Gabriel and his helpers had set up huge sound boxes and the music was deafening. He brought six young guys with him who were the chambelanes or chamberlains. With their bizarre hair styles and bright vests, they led the dancing. Yeira wore shoes the color of silver with huge heels; I don’t know how she was able to dance. This was her night, however.

When I left at 10 PM, the street was packed with people – the whole neighborhood. The fiesta continued until about 2 AM. Fortunately, because it’s a dangerous barrio, there were no problems or fights.

Sunday morning I went by the house. Elvira and Yeira were exhausted, Hector was still asleep and the street was full of trash. The dream had passed and reality had arrived. In the United States where my granddaughter lives, futures are almost guaranteed for young talents like Yeira and Hector. But here? How can you convert the dream of the quinceañera and the words of Pastor Galván into the future that Hector and Yeira want and deserve? How can the potential of these young people be realized?

Responses to “The Magic of Your Dreams”