I have always loved poetry, its power and resonance in the human heart; and I have always had an affinity for the Russian poets, especially those of the October Revolution of 1917, how they used their words to further that revolution.

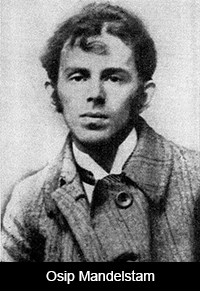

My meager study is cursory at best, a mere dip in a great sea of verse. Yet, it might whet your appetite to explore further, as Russian poetry holds a unique place in literature. As Joseph Brodsky says in his essay on Osip Mendelstam, “For those raised in the English-speaking world, it is difficult to comprehend that Russian poets have long had a political status as great as that as more public figures and that Russian poetry frequently has a political impact.”

Mendelstam recognized this about Russia, when he said, “only in our country is poetry respected.” He continued: “People are killed for it. And there’s nowhere else that people are killed for poetry.”

Mendelstam recognized this about Russia, when he said, “only in our country is poetry respected.” He continued: “People are killed for it. And there’s nowhere else that people are killed for poetry.”

Following Lenin’s death and the ascendancy of power that produced Stalin, censorship and suppression became the norm. Mendelstam was arrested in 1934, interrogated at Lubyanka, then exiled by an act of clemency. He was rearrested in 1938, sent to Second River, a transit camp near Vladivostok, in the Soviet Far East.

Mendelstam was last seen that December feeding off of the garbage heap in the camp.

Why was he considered so dangerous that he was victim of such odious treatment? One thing, he would not bend to the will of Stalin.

If our antagonists take me

And people stop talking with me;

If they confiscate the whole world—

The right to breathe & open doors

And affirm that existence will exist

And that the people, like a judge, will judge;

If they dare to keep me as an animal

And fling my food on the floor—

I won’t fall silent or deaden the agony,

But will write what I am free to write,

And yoking ten oxen to my voice

Will move my hand in the darkness like a plough

And fall with the full heaviness of the harvest…

He had written a poem in 1912 about Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. I too one day will create/Beauty from cruel weight. Mendelstam did not consider himself a political poet, yet his poems and the cruel weight of the Stalinist era brought his exile.

Yet, this was written in October of 1933, at the height of Stalin’s purges:

We live without feeling beneath us firm ground

At ten feet away you can’t hear the sound

Of any words but “the wild man in the Kremlin,

Slayer of peasants and soul-strangling gremlin.”

Each thick finger of his is as fat as a worm,

To his ten-ton words we all have to listen

His cockroach whiskers flicker and squirm

And his shining thigh-boots shimmer and glisten

Surrounding himself by scrawny-necked lords,

He plays on his servile half-human hordes

Some mewl, some grizzle, some moan,

Prodded by him, scourging us till we groan.

Like horseshoes he hammers out law after law

Slamming some in the gut and some in the eye

And some in the balls and some in the jaw;

At each execution, he belches his best

This Caucasian hero with his broad tribesman’s chest.

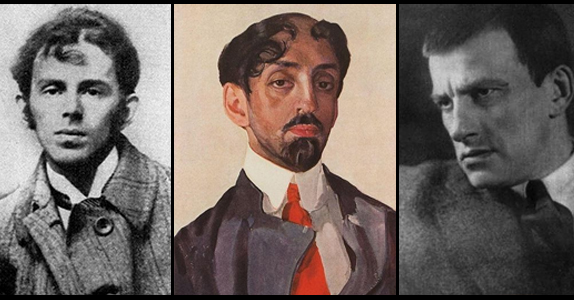

One individual who did see himself as political was Mikhail Kuzmin, novelist, critic, playwright, and poet, as well as a homosexual. He stood with Blok, Mayakovsky, and Anna Akhmatova, the other giants of Russian poetry.

One individual who did see himself as political was Mikhail Kuzmin, novelist, critic, playwright, and poet, as well as a homosexual. He stood with Blok, Mayakovsky, and Anna Akhmatova, the other giants of Russian poetry.

Kuzmin was a polymath, translating the libretti of Verdi’s operas; and French works on Beethoven and Rossini, Goethe (German), and classical literature, from Latin and ancient Greek. Also eight of Shakespeare’s plays, all published in Russian. Besides writing poetry, he wrote music for the new German Expressionist plays. One of his short stories “vies with the finest of the age,” as Michael Green writes in his book of Kuzmin’s work.

A favorite of the public and a darling of the Leningrad homosexual community, he had increasing trouble being published, had been cut out of journalism, and his health suffered; he died in 1936. Green writes: “We may doubt whether Kuzmin, had he lived a year or two longer, would have had the privilege of a natural death. In 1938 Yurkun (Kuzmin’s ex-lover) was arrested along with a number of other literary men and shot.”

Why do we know so little about these artists? Under Stalin much of what these writers wrote was unpublished; worse, under the Man of Steel many intellectuals and artists simply disappeared. Dimitri Shostakovich’s book Testamony describes what it was like to live in fear of this, and talks about the people who vanished, like Meyerhold, and how when that happened his friends did not mention his name for fear of being betrayed.

Poets seem to suffer because of their vision; but no poet in the West has ever faced the retribution of the State. A few in Russia, so famous, like Pasternak, were spared this fate but were perpetually threatened with exile. But others, whose names we shall never know, simply vanished. This period has left a great dark blot on the culture of Russia, and it has deprived the world of many creative voices.

Poets seem to suffer because of their vision; but no poet in the West has ever faced the retribution of the State. A few in Russia, so famous, like Pasternak, were spared this fate but were perpetually threatened with exile. But others, whose names we shall never know, simply vanished. This period has left a great dark blot on the culture of Russia, and it has deprived the world of many creative voices.

Reading their stories, recounting those lost lives and cruel government policies, the question that arises for me is, how would I act under similar conditions? I hope I’m never put the test.

Perhaps the great Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, who, frustrated in love, alienated from Soviet reality, attacked by insensitive critics in the press, and denied a visa to travel abroad, committed suicide in Moscow on April 14, 1930. He was thirty-six. But he has left us a poem that describes what drove him on:

I know the power of words,

I know the tocsin of words.

They are not those

that make theater boxes applaud.

Words like that

make coffins break out

Make them

Pace

with their four oak legs.

It happens—

they are thrown out,

not printed, not published.

But the word gallops,

its saddle girth tightened,

it rings through the ages

and trains creep nearer

to lick

poetry’s

toil-hardened hands.

Responses to “The Lost Poets of the Russian Revolution”