“He always told his students to cry at night; and in the day just to listen calmly to what the bones were saying.”

—Obituary of forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow in The Economist, May 24, 2014.

I disliked my job from the first day, but until that long night in April 1968, I didn’t hate it. I told myself over and over that I took the job because I didn’t have a choice, because I needed a job and there it was. But like most of the things I told myself, then and later, it wasn’t true. I had choices and I made them.

I was married, with two young step-children and a newly minted honorable discharge certificate from the U.S. Army as a private first class. I had survived the worst two years of my life, and now it was time to pursue my career, my dream, my obsession of journalism. For three months I dithered, taking graduate classes in international relations at Columbia University, then finally got serious about hunting for a job.

The first of the big city papers to offer me a job was the Baltimore Sun. At that time The Sun was ranked by just about everybody as one of the three best papers in the nation, after the New York Times and the Washington Post. Both my wife and I had lived in Maryland before I was drafted into the Army. Although I was a native of Georgia and she of Ohio, it was our adopted home, and The Sun was our hometown paper. So I made my choice, although at the time it seemed like no choice at all.

Then I had to make another choice. The Sun actually offered me two jobs: reporting from their bureau in Salisbury, a small town that was the largest community on the Eastern Shore, a rural area of clam and crab fishermen and tobacco farmers; or copy editor in the newsroom in the main office in Baltimore. I wanted to write, not edit, but my wife and I had both lived in Leonardtown, Md., another small rural county seat of fishermen and farmers, and I told her we had had enough of that kind of life. What I meant was I had had enough. Maybe I was afraid of returning to the claustrophobia of a rural small town. Maybe it felt too much like returning to the past rather than fulfilling the preposterous idea I had then that life was a steady march into the future. Maybe I feared, not for the last time, as I did years later when I turned down The Sun’s offer of Moscow Bureau chief, that the wrong kind of life would undermine my wife’s sanity and our marriage’s stability—hers and its survival, their tacit precariousness. So I made my second choice which seemed like no choice and became a copy editor.

We rented a house in Baltimore, an old wooden house in northeast Baltimore a block from Gaucher College and a 15-minute bus ride from The Sun building downtown.

Like most of the other members of the copy desk, I worked nights, from 5 p.m. to 2 a.m., the hours when stories were written and edited for the three daily editions printed each night.

A dozen of us sat around a huge horseshoe-shaped table with the slot man in the middle coordinating our work, handing out stories to be edited and quickly scanning the finished product before sending it downstairs to the composing room, where linotype machines turned the typed lines on paper into slugs of hot metal. We were the last stop, the gateway between the battalion of reporters and editors in the newsroom and the blue color army in the composing room. We did the final edits, checking punctuation grammar, spelling, paragraphing and factual accuracy. We cut the stories back to their assigned length. Finally, we wrote the headlines created to attract readers to the blocks of unrelieved gray type that in those long-ago and seemingly innocent days were all that The Sun uncompromisingly presented to its hardy readers.

It was our job to make sure the words conformed to Webster’s Dictionary and the style conformed to the unique stylebook that The Sun published. Unlike almost everybody else in the American journalistic world, we didn’t use the standard Associated Press stylebook or even the New York Times stylebook. The Sun had its own way of doing things, the result of proud traditions that went all the way back to the early 19th century, and it wasn’t about to adopt some other paper’s ways.

One of The Sun’s ways involved race. Baltimore had always had a lot of blacks. West Baltimore was almost entirely a black ghetto. We had one way of treating whites, with old-fashioned courtesy, and another way of treating blacks, equally old-fashioned, patronizing at its best and contemptuous at its worst.

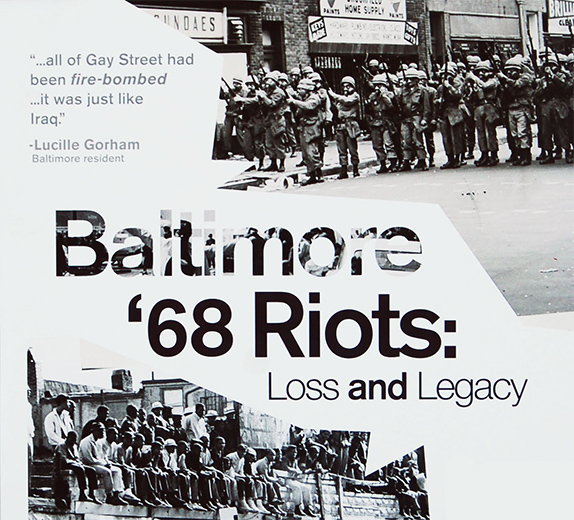

As usual on that April night, I took the bus into work, then took my seat at the big table in the center of the newsroom. I had been sitting at that table for two years, neither the newest nor the longest-serving member of the crew but at 27 the youngest. I was also neither the best nor the worst on the desk. While my headlines were often the pithiest and got praised in the city editor’s periodic newsletter of winners and sinners, I was a sloppy editor, often overlooking typographical errors and grammatical gaffes. As a result, I usually got the routine stories, not the page one leaders. So it seemed typical that night when I was handed a wire service story on a couple of minor riots in black neighborhoods. Later, because I had started down this path, I was given a story on a more serious riot in Chicago, then on a very bad one in Washington, D.C., and finally a human tsunami in West Baltimore itself. Before it was all over, more than a hundred cities were in flames and thousands of soldiers with loaded rifles were patrolling the streets of Washington, Baltimore and Chicago.

It was my job to edit these stories coolly, objectively, precisely. There was no room for emotion, for sorrow, for tragedy. In between riot stories, I edited the usual local crime stories. One was a short, two or three paragraphs, a summary of a notation in the police log about a murder of a child in West Baltimore, clearly a black child whose parents were referred to by their surnames. Another was a long story about the death of a businessman in all-white north Baltimore, clearly a white man, the owner of a chain of retail stores, who was respectfully titled Mr. He had committed suicide, but the reporter was not allowed to say so. Much of our readership was Roman Catholic, and a suicide could not be buried in a Catholic cemetery or receive holy rites. Such were the hypocrisies of what was universally considered a great newspaper.

Hour after hour, the reports of riots around the country poured into my desk. Blacks said the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. had been the last straw. Whites said they could not understand what was happening. The gap in communication, in comprehension yawned so wide it seemed it could never be spanned.

I wanted to cry that night with the reams of copy pouring onto the desk in front of me, stories of deaths and injuries, tears and screams, anger and sorrow, broken bodies and bloodied streets. I wanted to stop and think about what was happening, but there was no time. I wanted to stop and cry, but I could not.

That night at 2 a.m. I did not wait for the bus outside the newspaper. I started walking, and walked all those silent, lonely miles home. Baltimore was rioting on the west side, but this was the east side and it seemed calm, empty except for me, silent except for my footsteps and my sobs. I could not stop crying, and when I got home an hour later and walked into my house where my wife and the children slept peacefully, I was still crying. Tomorrow I would have to put tears aside and again sit down at my desk and edit stories of a nation falling to pieces.

(Photo by Nick Hum)

Responses to “The Longest Night”