It’s Sunday morning and I’m driving through the desert east of Juárez, Mexico, only a few miles from the New Mexico border. Suddenly I see a scraggly line of some thirty or forty men and women coming towards me in the sandy pathway that parallels the two lane highway. The first man wears a long, maroon colored bathrobe and tennis shoes with no laces. The second is stocky with a round face and holds a plastic airplane in one hand. His pant legs are torn, about eighteen inches too long and drag behind him as he shuffles along. On the edge of the highway itself, a man pushes a wheelchair with an older woman in it. She is waving and laughing. Two boys on bicycles are circling back and forth, also on the edge of the highway.

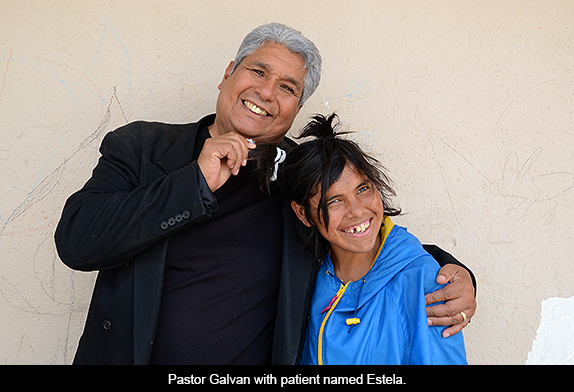

These are mental patients in Visión en Acción, a private asylum founded by Pastor José Antonio Galván, an ex-addict who repented and has spent the last eighteen years caring for approximately one hundred of Juárez’s mentally ill. These are the James Boyds of this city that has suffered so much.

Boyd had an extensive record of arrests, many of them for violence. The same is true of Galván’s patients. Arón was a “sicario” or gunman in Juárez, spent close to twenty years in the infamous Islas Marias prison and is alleged to have killed a minimum of fifteen people. Josué, a former Los Angeles gang member, served nine years in California prisons like San Quentin and shot a man to death in Florida. Oscar, now deceased, was an enforcer for the Azteca gang. Yogi, the stocky, incoherent man with the too-long pants crushed a man to death. Becky beat another woman to death in an argument over one cigarette.

How is it that men and women like these have found peace in Galván’s asylum? As Dr. Albert Dugan stated in “A ‘Disposable’ Life,” the article by Patrick Malone and Daniel J. Chacón in the April 6 New Mexican, “This disease (mental illness) divides people. It’s an isolating disease.” One of Boyd’s lawyers, John McCall stated, “We’ve developed this multi-tiered society where we treat people like James Boyd as disposable humans.”

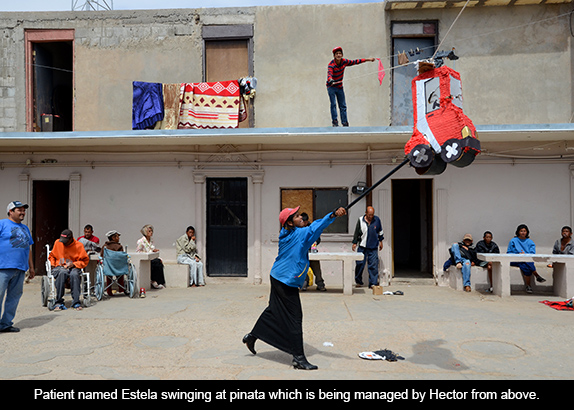

Pastor Galván would agree. He has repeatedly said that most people treat the mentally ill as “basura humana” or human garbage. What’s different is that he treats his patients as “tesoros escondidos” or hidden treasures. His goal is to give them a sense of productivity, usefulness and dignity. For example, lacking the kind of government reimbursements that we’re accustomed to, most of the running of his asylum is done by patients – from washing the clothing and blankets, helping prepare and serve the food and gathering firewood in the desert to care-related issues like bathing, shaving and brushing the teeth of those who are more handicapped and consoling and calming those who are becoming agitated.

In the United States, mental health is too often about money. In Colorado, my home state, $22 million of new state funds has been unavailable for a system of crisis centers because of a court battle over who gets the contract to run the program. Here in New Mexico, Governor Martinez’s power grab of the mental health system has also been about who gets the reimbursements. No one – not the Attorney General who has been dawdling over an audit for some nine months, not the legislature whose session recently ended, not the providers of the affected centers, not the supposed advocates like the National Alliance on Mental Illness of which I’m a member - has stood up and fought back. No one said, “We’re going to see these people for what they are. Human treasures and not just numbers from whom to collect a reimbursement. And we’re going to fight for them.”

In the middle of this scraggly line of patients is a tall man in black holding what looks like a shepherd’s staff. It’s Galván with his flock. The two boys on bicycles are Hector (16) and Ángel ( 14) and they’re patrolling the highway so that none of his patients can wander up into the traffic. They’re like the sheepdogs and he is the pastor or herder. But he knows his flock is not going to run off because he has given them a home and a family. He’s proving that there’s something more important than money. Dignity, caring, being productive. My bet is that someone like him could have broken through the isolation that doomed James Boyd.

Responses to “The James Boyds of Juárez”