A turbulent week in New Mexico’s biggest city climaxed on Cinco de Mayo with a historic citizen takeover of an Albuquerque City Council meeting, as a deepening governance and justice crisis kept testing the meanings of democracy, public safety and the rule of law in the United States of the early 21st century.

And at a time when public patience is reaching a breaking point over new officer-involved shootings, one of the biggest questions is: Can the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) make a difference in the management and accountability of Albuquerque’s police department? The answer to that question and much more was on the minds of many people who turned out for three well-attended public meetings sponsored by the DOJ in the Duke City during the past week.

The purpose of the gatherings was to receive public recommendations for a forthcoming agreement between the DOJ and the City of Albuquerque to reform police recruitment, training, standard operating procedures and oversight.

Given the size of the police department, as well as the possible precedent-setting character of any agreement that is reached, the impact of a DOJ-Albuquerque accord will likely extend across New Mexico and even beyond.

“This is a very important time, because community input is going to forge this agreement,” Damon Martinez, acting US attorney for New Mexico, pledged at the meetings’ kickoff.

Staged at the Alamosa Community Center on Albuquerque’s West Side, the first session got off to a rocky start when members of the public expressed surprise and disagreement with the DOJ’s planned format of splitting the audience into small focus groups. Some residents said they preferred a big meeting format so public grievances could be openly vented.

Finally, both formats prevailed.

Held one week after the fatal April 21 police shooting of 19-year-old Mary Hawkes, community residents sounded a sense of urgency.

“We have children being shot by the police now,” said artist Barbara Grothus. “(Hawkes) was a young woman who didn’t have an opportunity to make her life better.”

(According to the Albuquerque Police Department (APD) Hawkes was shot to death by officer Jeremy Dear after she pulled a gun on him during a chase in the city’s Southeast Heights. More than two weeks after the killing, many questions remain unanswered about the deadly encounter; no video from Dear’s lapel camera could be recovered, according to an earlier statement by APD Chief Gorden Eden.)

Charlie Zdravesky, a former KUNM oldies show host and the producer of the old “Outta Joint at the Joint” musical shows at the state penitentiary, called on the DOJ to pressure local officials blamed for more than 20 officer-involved fatal shootings and related legal irregularities since 2010.

“Are the mayor, police chief and district attorney going to be held accountable?” Zdravesky demanded. “You folks in the DOJ have to force them to do something.”

The DOJ’s Luis Saucedo explained the legal parameters and historical context of his department’s involvement in Albuquerque, which culminated an extensive 16-month investigation last month with the release of a highly critical report on APD’s use of deadly and less-than-lethal force.

“This level of unjustified, deadly force by the police poses unacceptable risks to the Albuquerque community,” the DOJ wrote to Mayor Richard Berry.

According to Saucedo, the federal statute on which the DOJ based its investigation grew out of the Rodney King beating by Los Angeles police officers.

The next step, Saucedo said, will be for the DOJ to negotiate a legal agreement for reforms with the City of Albuquerque, or consent decree, which will be overseen by an appointed monitor. If the negotiations do not bear fruit, the DOJ has the power to take the city to court, he said.

In regards to timelines, Saucedo said the DOJ was prepared to stay in Albuquerque “until the agreement is implemented.” Saucedo emphasized that a successful agreement depends on the local buy-in, especially the establishment of a vigorous, independent citizen oversight body-an issue which is lingering in the Albuquerque City Council.

“DOJ can’t be here for 100 years policing the police,” he stressed. Saucedo said the DOJ is overseeing policing reforms in Seattle, New Orleans, the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, and other places. The federal official credited the DOJ for cleaning up the Los Angeles Police Department in the wake of the notorious Rampart Division Scandal involving corrupt narcotics squad officers.

Some attendees questioned the role of lawyer Scott Greenwood, who’s been hired by the City of Albuquerque to assist with the DOJ negotiations. Flashing a determined look, Greenwood countered that he’s got a background as a plaintiff’s attorney with a proven track record in reforming the police force in his home base of Cinncinati.

“(Reform) happened in L.A., Cinncinati, and it will happen in Albuquerque,” Greenwood insisted. “I’m the wrong guy if you’re expecting a whitewash.”

One audience member asked, “Are you going after reform or restructuring?”

“Both,” Greenwood replied.

Activist Ken Ellis II, father of an Iraq war veteran who was shot to death by the APD in 2010, Ken Ellis III, broached the matter of impunity. The officer who shot his son has since been promoted and “given more bullets,” Ellis said. “There needs to be officers held accountable,” he declared.

After the April 28 West Side meeting, public passions continued to flow at two subsequent meetings held during the week. At the Cesar Chavez Community Center in the Southeast Heights, residents variously urged improved police-community relations, greater public involvement in police oversight, drug-testing of officers, classes in wellness and PTSD, better attention to returning military veterans, and public participation in the DOJ-City of Albuquerque negotiations.

A sign at the event perhaps captured the essence of the issue: “The problem is bigger than just the police department.”

Michael Patterson, a former UNM Lobos athlete who currently works as a teacher, said school children view the police as the enemy and should be exposed to flesh-and-blood officers.

“We obviously have a problem. I don’t know if we have one solution. There has been a lot of finger-pointing,” Patterson said. While hesitating to place blame, Patterson said Albuquerque needs “strong leadership” to avoid further spinning out of control.

Mary Jobe, whose fiancé, Daniel Tillison, was shot and killed by APD in 2012, said her husband was a “criminal,” but that fact alone did not give the police department license to kill him.

“He needed help, he had drug problems,”Jobe said. The Tillison shooting was one of the cases investigated by the DOJ; the federal agency reported that Tillison was not armed when he was killed.

Jobe, who has been one of the most visible activists in the movement against police violence, complained of recent bouts of harassment. “There are good cops out there and I try to support them, but it’s hard when they’re constantly pulling you over,” she said.

Jobe is not the only activist to complain of surveillance and harassment.

Reached later by phone, Nora Tachias Anaya of the October 22 Coalition said men she believes are police officers have regularly tailed and photographed her ever since she got involved in the anti-police violence movement two years ago.

“We haven’t shot anyone. We haven’t mauled anyone. We aren’t radicals. I beg to differ,” Anaya said. “I’ve never had a ticket I didn’t pay. I’ve never been in jail. Yet I am profiled.”

Stephanie Lopez, Albuquerque Police Officers Union president, briefly addressed the crowd at the Cesar Chavez Community Center.

In comments to FNS, Lopez said the union supported a “fair and equitable” reform agreement between the DOJ and municipal administration of Mayor Richard Berry that does not “violate the officers’ rights.”

Asked her opinion on officer’s use of lapel video cameras to record interactions with citizens, Lopez said she supports the activation of the devices during police-citizen encounters but considers proposals to have the cameras turned on during an entire work shift as impractical.

The union leader said recent media coverage of the Albuquerque crisis has not proceeded in a “fair manner,” with released video footage jump-starting a preliminary investigation in at least one case.

Lopez said another problem was the staffing shortage in APD, which is occurring in the midst of a larger professional crisis. Although the APD’S personnel level is already down by the 300 officers from the 1100-strong force of 7 years ago, the ideal number of officers should be at 1300 according to Albuquerque’s population and FBI standards, Lopez said. Overall, only 400 officers are available to patrol a big city, with the average squad consisting of less than five officers, she added.

At one point during the interview, Lopez read a text from an officer that lamented working conditions and the lack of public understanding of the challenges and sacrifices faced every day by rank-and-file police.

In addition, individual officers or their children-herself included-have been subjected to threats, residential vandalism and shots fired at their homes for some time now, she insisted.

In terms of the upcoming DOJ negotiations, Lopez said she wanted a “fair balance between the community and the profession.”

The DOJ meetings attracted residents with long-standing grievances they contend were never given a fair shake. For instance, sisters Rosella and Roberta Farmer spoke to the DOJ about the 2010 police slaying of Rosella’s husband, Alex Sinkevitch.

According to the Farmer sisters, Sinkevitch was shot in the back and left to bleed to death on the floor of his home. The APD wasn’t interested in interviewing witnesses, and a video camera that might have captured the shooting incident was mysteriously missing one week later, they said.

Lupe Lopez-Haynes, sister of a long missing woman, Beatrice Lopez Cuberos, showed up at one meeting contemplating the possibility of speaking to DOJ representatives about her frustrations with the APD’S handling of her sister’s case. But at the last minute, Lopez-Haynes decided against speaking to the DOJ.

“I don’t think we’re getting anywhere,” she later told FNS. “If I’m going to speak, I want a lot of people to hear. I want to see some action. I’m just waiting for some action…it needs to be cleaned up on the inside.”

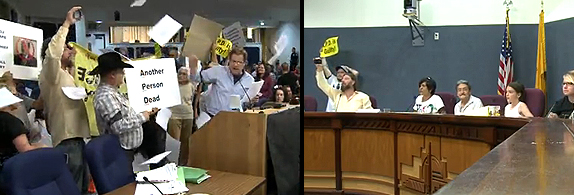

Lopez-Haynes spent the evening of May 5, Cinco de Mayo, at home, but the Albuquerque resident’s desire for stronger action was fulfilled. Dozens of protesters, including family members of men shot to death by APD during the last four years, occupied the Albuquerque City Council meeting.

The protestors attempted to serve an “arrest warrant” on police Chief Eden for accessory to second degree murder in the slayings of James Boyd, Alfred Redwine, Mary Hawkes and Armand Martin. “You are walking away from justice,” activist David Correia was quoted, as Eden fled the scene.

Once in control of the council’s chambers, the citizens formed the People’s Assembly of Albuquerque and passed resolutions that declared no confidence in Mayor Richard Berry and Chief Administrative Officer Rob Perry; called for the immediate resignation of Chief Eden; the implementation of an independent civilian police oversight commission with the ability to discipline, hire and fire officers; and the inclusion in the DOJ-Albuquerque consent decree of a provision that officers not having their lapel cameras turned on during encounters with civilians face immediate firing.

A participant in the City Council takeover, Nora Tachias-Anaya said the event was an “empowering” one that made her feel like she was in “heaven.”

The people, she said, were tired of city councilors waiting for the DOJ to act. Tachias-Anaya said she told new Councilor Klarissa Pena, who represents Albuquerque’s West Side, to “do her homework” on issues like the 11 women found murdered on the West Mesa in 2009.

In a press statement, City Council President Ken Sanchez said he was forced to adjourn the official meeting and reschedule it for Thursday, May 9, due to public safety concerns.

“It’s unfortunate that the Council was not able to hear from everyone who signed up to speak, and was not able to complete some very important business on tonight’s agenda,” Sanchez said

Tachias-Anaya said the popular movement will keep pressuring the City Council and other authorities.

“The movement is growing and we are not going to stop. The fact is, I have rocket fuel in my tank and I’m not going to vary from that,” she said. “We are going to be in their faces. We are in the movement now.”

Stoking activists’ anger was the May 3 police shooting of United States Air Force veteran Armand Martin by the APD, after a day-long stand-off at the man’s home. On the same day, New Mexico state policemen critically wounded Daniel Olguin in a similar incident in Los Lunas, a town located south of Albuquerque. In both instances, the men were reported to have fired guns. And in both events, domestic violence, substance abuse, mental health issues, and access to firearms were variously reported as factors.

By multiple measures, the clock in Albuquerque is ticking louder and louder and already well past midnight.

Responses to “The Clock in Albuquerque Strikes Midnight”