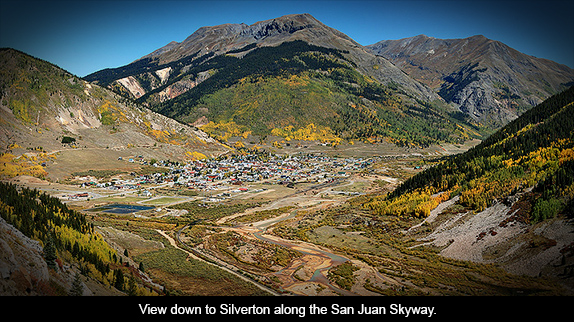

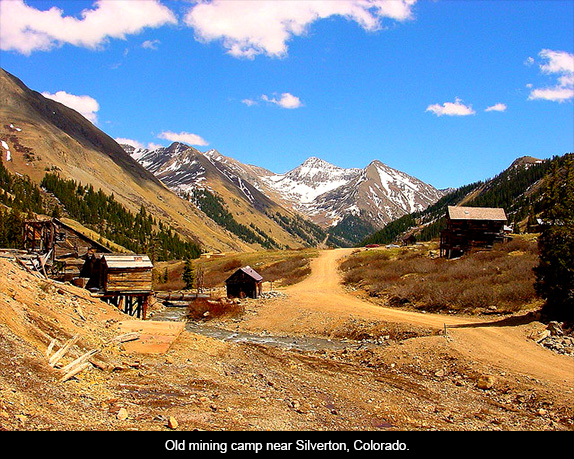

Silverton, Colorado, lives and dies and lives again by the cycle of seasons. Yet this spirited San Juan Mountain village has one constant, one specter of the past haunting its present. Silverton’s orange and yellow phantom creeps out of the orphaned mines in the surrounding mountains. But this is not another regional ghost story about murdered saloon girls or wronged cowboys.

In short: the old abandoned mines bleed out eight hundred gallons a minute of toxic metal-laden water into the Animas River. The metals and salts flow through Durango, Colorado, into Farmington, New Mexico, and on into the Colorado River.

The resulting facts are hard to ignore. Three of the four fish species in the upper Animas have vanished, and both the diversity of insect species and the quantity of insects have nose-dived. The levels of zinc in the Animas just north of Durango are toxic to animals (to which group humans belong, no matter how often we deny it).

The Mercury covered this toxic stalemate on the Animas in depth last year. Since then, the Animas River Stakeholders Group has continued to do everything in its power to prepare remediation efforts on the area’s water, including holding a competition for creative solutions. However, legal liabilities prevent the group from actually taking any measures. To further complicate any potential, the group operates on consensus among stakeholders. (Just how often do you think mining companies and environmentally concerned citizens reach consensus on anything?) It also has nowhere near the budget needed to operate a proposed limestone water treatment plant: $12 to $17 million, with $1 million a year in operating costs from now to eternity. Pocket change to some corporations, but not to places like Silverton, the only incorporated municipality in all of San Juan County.

Enter Superfund, which sounds like a monetary superhero and in many ways is. Superfund is a program under the Environmental Protection Agency that enables the federal government to oversee hazardous waste sites. The EPA offers legal protection to the local entities with which it collaborates, and it also compels those responsible for pollution to manage or pay for the cleanups.

Yet Silverton has resisted Superfund aid for years. A Superfund site used to carry a stigma; the label could make a place sound as horrific as Chernobyl. The town has worried that by acknowledging its serious pollution, tourists (and their dollars) would turn elsewhere. Silverton of all places knows what such desolation would look like—it already happens every year.

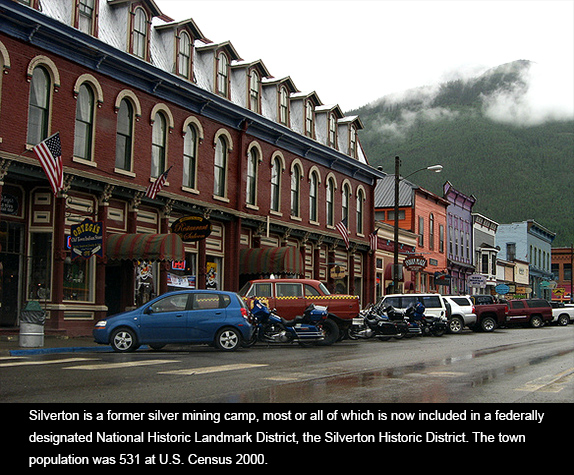

From November through April, boards gag most of the storefront windows. There’s no whisper of traffic, no ambient music, no televisions leaking sound onto the sidewalk. Just the whistle of wind and the chittering of creeks. I’ve strolled the whole length of Greene Street, Silverton’s main thoroughfare, without seeing another human being. On that visit, only one gift shop, one coffee shop, and one diner were open for business. Our waitress assumed we were either on our way to Telluride, or on our way back. If you miss the peak snow season, there’s simply no plausible reason for traveling to Silverton.

In May, the color returns to the town’s cheeks. The population swells to its official 600-some-odd residents, and the shops and restaurants stretch from their slumber. These businesses are how Silvertonians make a living these days, but folks still talk about mining returning to the area like a once-and-future king. This is an old mining town through and through, and if you can squint away the tee-shirts in the storefronts, you sense the place’s authenticity. Heck, most of the streets aren’t even paved. This proud little town once boasted four different railroads servicing its mines; now, it has just the one historic narrow gauge, and through October, it provides most of the town’s economic support. Only now, instead of carting away ore, it carts in tourists.

Such tourism is gold to a Colorado town built on precious metals. With that perspective in mind, I have an easier time understanding Silverton’s decades-long resistance to admitting it needs federal help stitching its hidden wounds. Relying on the ARSG and other good Samaritans meant keeping issues in the family, as it were, and thus keeping the problem quieter.

But times are changing. As the general public grows more conscious of environmental stewardship, the Superfund label shifts. It no longer howls “Danger! Stay Away!” but instead says, increasingly, “This community cares about restoring health and vitality to itself. We take responsibility for our past, in order to preserve it for people like you.”

And Silverton, that out-of-time village nestled in the remotest Rocky Mountains, seems to be changing with the times.

On April 23, officials from the EPA met with San Juan County commissioners and Silverton residents to answer questions about Superfund designation. The EPA officials assured the assemblage that the agency would not pursue Superfund without Silverton’s approval, and that the cleanup process would continue to be a collaborative effort with the community. Nothing has been decided, but for the first time, Silverton is publicly curious about pursuing serious cleanup of the orphan mine leakage.

The first step in addressing any problem is admitting there is a problem. For Silverton’s future, whether that’s in continued tourism or the return of mining, addressing its pollution catastrophes will ensure long-term sustainability over short-term saving face.

Environmental wounds can’t be papered and painted over. Just as with wounds in the human body, they need air—a concept Silverton and San Juan County appear to be coming to understand. If they succeed in addressing their orphan mine waste, the town can remain vital instead of decaying into just another dolled-up tourist façade haunted by what-once-was and what-might-have-been.

(Photo credits in order of appearance: Silverton in San Juan Valley by Tobias; Aerial view of the Animas river by Doc Searls; Silverton street and storefronts by Ken Lund (caption from Wikipedia); Mining ghost town outside Silverton by Gloria Manna)

Responses to “Silverton’s Current Hope”