On Wednesday, January 7, 2015 three armed men burst into the offices of Charlie Hebdo, the satirical paper that has published a number of extreme caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad in recent years, some of them frankly pornographic. The men were Muslim fundamentalist extremists, out for revenge. They opened fire on an editorial meeting, killing the editor and several cartoonists. Before the horrific incident was over, 12 people were dead.

In the finely honed spirit of French satire, Charlie Hebdo has been poking what some would term religious fundamentalism’s defensive self-image since 2006, when the publication reprinted a Danish newspaper’s cartoons—also mocking the Prophet. Eventually the Danish cartoonist was murdered. In 2011 Charlie Hebdo was firebombed after publishing a spoof issue, Charia Hebdo (a play on the word for Shariah law). Here in the US we have our own versions of spoof publishing, most evident in The Onion. But while The Onion spoofs everyone and everything, much of Charlie Hebdo’s mockery is aimed at the religious extremism threatening to consolidate Inquisition values in the modern age.

It seems to me there are several issues here.

The first is the tragedy of 12 lives lost. As with other such outrageous acts of violence—from the 3,000 murders in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania on September 11, 2001 to the 1995 devastation of the federal building in Oklahoma City, the Boston marathon bombing, or a suicide attack in the name of Allah claiming a half dozen lives anywhere in the Middle East—only a perpetrator who places no value on life or humanity chooses such a response to what he or she perceives as crimes against their beliefs. Charlie Hebdo’s use of provocation in print belongs to a tradition that dates to long before the French Revolution. Those who would murder the practitioners of that tradition are nothing more than thugs.

I would caution, though, against equating all the murderers with this strain of Islam gone awry. Christian, Jewish, Hindu and Buddhist fundamentalists are responsible for their share of the violence. So are political ideologies that so often brandish a dogma more religious than political. Extremist religious beliefs, like their secular counterparts, occur in all cultures. The US National Security religion of first-strike warfare murders innocent people every day. The immunity our system bestows on overly armed police when they kill unarmed black youth has also become a religion here, as has our national devotion to the power of the NRA.

Dogma, whether religious or secular, inevitably leads to drinking the cyanide-laced Kool Aid. Following the January 7th attack on Charlie Hebdo, the Indian born British novelist Salman Rushdie wrote: “Religion, a mediaeval form of unreason, when combined with modern weaponry becomes a real threat to our freedoms. This religious totalitarianism has caused a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam and we see the tragic consequences in Paris today. I stand with Charlie Hebdo, as we all must, to defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty and stupidity. ‘Respect for religion’ has become a code phrase meaning ‘fear of religion.’ Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect.”

I too stand with Charlie Hebdo. Where else would I stand?

Rushdie knows personally of what he speaks. His 1988 novel, The Satanic Verses, was seen as a threat to Moslem values by extremists of that religion; and the supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa calling for his assassination the following year. Rushdie was forced to go into hiding, and became a symbol of freedom of thought throughout the Western world.

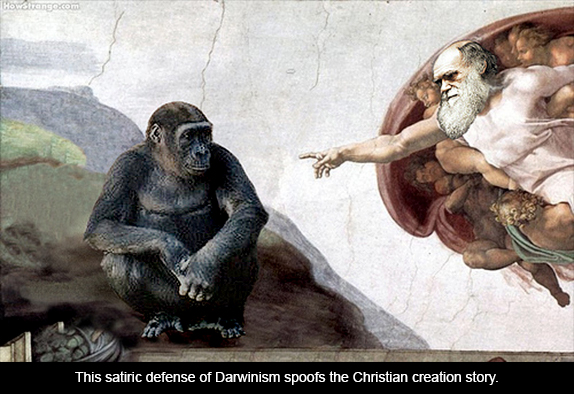

Many great minds have dismissed the idea of God and blind obedience to whatever interpretation of His Will may be put forth by a variety of religious institutions. Stephen Hawking’s conclusion that God is a human invention is well known: “Modern physics leaves no place for God in the creation of the universe,” he has said. And yet, we continue to struggle in this country to keep the intellectually limiting ideas of creationism and so-called intelligent design out of our classrooms.

So this is one issue: the worldwide power religious beliefs have exerted to put forth a single, invented, truth, and the heresy implicit in questioning that “truth.” Fundamentalists of all stripes share an inability to accept any opposition to what they consider the word of God. Discussion is impossible, challenge out of the question. Some Christian fundamentalist sects go so far as to warn followers that Satan speaks in reason’s voice; dissenting ideas must be rejected on the grounds that they test the believer’s faith. The only language many of these people understand is one of violence. Which is precisely why we must oppose them with words and pictures, not deeds.

This presents a related problem: when we oppose with words or pictures, is there such a thing as going too far? What do we consider legitimate critique, and when does that critique make unnecessary inroads into another’s dignity? The answers to these questions shift in relation to the degree to which the believer demands unfailing allegiance or subscribes to a live-and-let-live philosophy. Generally, those most comfortable with their own beliefs allow that others may not share them, those most rigid and fearful recoil at any other point of view. Charlie Hebdo certainly pushes the envelope each time it portrays Mohammed in frankly pornographic terms. Yet its brashness is part of a time honored tradition.

I myself have had some experience with the issue of dissent. In 1985 I was ordered deported from the United States, the country where I was born, because of opinions expressed in several of my books. These opinions disagreed with US governmental policy in Southeast Asia and Central America. One of the 34 clauses of the 1952 McCarran-Walter Immigration and Nationality Act, commonly referred to as “the ideological exclusion clause,” rendered such opinions grounds for deportation. At trial I was accused of having edited a literary magazine that published communists (alongside Catholics and others), asked why I had modeled nude for art classes in the 1950s and if I had ever “written a poem in praise of free enterprise.” My case lasted almost five years. I was never firebombed or shot. But I was beaten up in my UNM office one day, and some of the hate mail I received promised much worse.

I won my case in 1989. It was a victory for freedom of speech and dissent. But US immigration law in general went from bad to worse, and soon Arabs and practitioners of Islam took the place of communists on the list of those deemed inadmissible. Racism and fear of difference have long been used to keep people in line.

For many, the difference between freedom of speech and an assault (even a non-lethal assault) on another person is difficult to determine. Not too many years ago, at the University of New Mexico, an English professor involved some of her students in sadomasochistic activity exposed on an Internet web site. Several of her colleagues protested. They felt that the professor in question was abusing the teacher/student relationship. The University defended the professor; it argued that the activities in question fell under the rubric of freedom of expression. I don’t doubt that they did. But the more important issue, for me, was that a professor who in any way abuses his or her relationship with students, with whom there is always a power differential, creates an unfair and ultimately controlling situation. I believe the university should have defended its students.

There is something analogous between this case and Charlie Hebdo’s anti-Mohammed cartoons. Freedom of speech certainly supports the publication of the cartoons. But did the cartoonists have to stoop to such painful attacks on a figure held sacred by large numbers of people? Is pornography the best weapon against blind belief? Perhaps those of us who see fundamentalism as one of civilization’s greatest threats should be setting a more respectful example when we defy it. Needless to say, I am not making an argument that in any way defends the murder of those cartoonists.

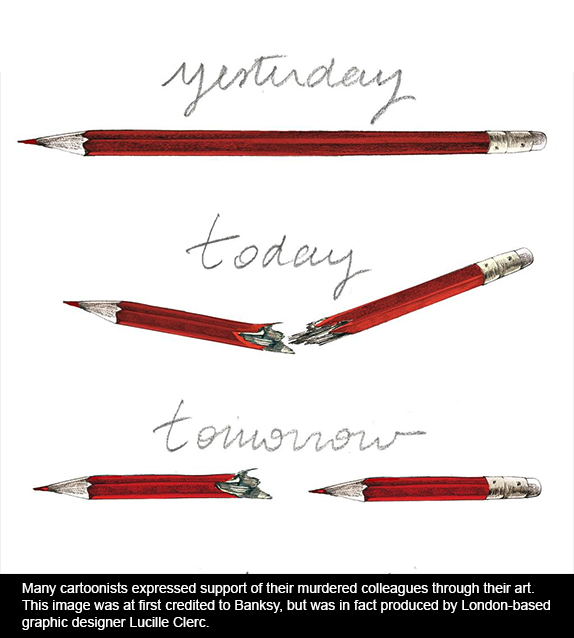

And who were the cartoonists who died beneath the attackers bullets at Charlie Hebdo’s offices? Two of them, Jean Cabut (Cabu) and Georges Wolinski, were 76 and 80 years old respectively. Both were brilliant, both beloved. They grew up in a France that responded to the stifling postwar 1950s, and De Gaulle’s subsequent paternalism, with l’esprit frondeur or slingshot wit. Like many 1960s rebels they got their feet wet during the Paris May of 1968, the French version of youthful rebellion exploding at the time in New York, Mexico City, and elsewhere.

As Andrew Hussey wrote, in “French Humor, Turned Into Tragedy” (New York Times, January 8, 2015): “What was gunned down on Wednesday in Paris was a generation that believed foremost in the freedom to say what you like to whomever you like […] pride themselves […] on free thinking and a love of provocation, that always stands in opposition to authority. The awful killings are the direct opposite of all that: the merciless massacre of the Parisian mind.”

We might substitute the Russian, Chinese, Egyptian, or American mind. Charlie Hebdo. Pussy Riot. The lone youth standing before a tank in Tiananmen Square. Journalists imprisoned in metal cages in Cairo for reporting the news, or embedded here so they will write the official story that substantiates official policy. There is always an official story. Hopefully, there will always be those who question, oppose or defy it.

(Images: Darwin creationism image taken from thoughtful essay on carlproper.com entitled, “Spinoza’s God.” If you know the artist who tweaked the original, please .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address). “Yesterday, today, tomorrow” by Lucille Clerc.)

Responses to “Satire vs. Fundamentalism”