Rivers like deserts don’t respect international boundaries. The Sonoran Desert, the hottest and most biologically diverse of the four North American deserts, spreads down into Sonora from Arizona. Similarly, the headwaters of the Yaqui River originate in the “Sky Islands” (outcrops of the Continental Divide) of southeastern Arizona.

Fed by tributaries created by the runoff and snowmelt of the Sierra Madre Occidental, the Yaqui River becomes Sonora’s largest river as it descends south through narrow canyons before heading west toward the sea. As it turns west toward the Sonoran Desert and the Gulf of California, the Río Yaqui leaves behind the semi-arid conditions, narrow canyons, and higher elevations of eastern Sonora.

The Yaqui River established the natural foundation for the agricultural development in the 20th century of the arid coastal plains of southeastern Sonora. For many centuries prior to the agribusiness boom in the lower Yaqui River basin, the river was the center of the life of the Yaqui people, enabling farming in the river’s floodplain and providing drinking water.

But the Yaqui River was problematic for agricultural investors. In the dry months, the flow of the river diminished – sometimes so much that water no longer could be diverted into irrigation canals. Over the millennia, the river flowed over its banks creating a delta of rich alluvial soil. While this delta was the product of annual flooding, farming the delta land in the Yaqui Valley suffered from floods.

To solve these problems, the Yaqui Valley’s agricultural investors worked closely with the federal government to build three dams and reservoirs: La Angostura, El Novillo, and Oviáchic. Funding from Conagua and its predecessor agencies also underwrote the construction and maintenance of large canal that transferred water from the Oviáchic reservoir to the Yaqui Valley.

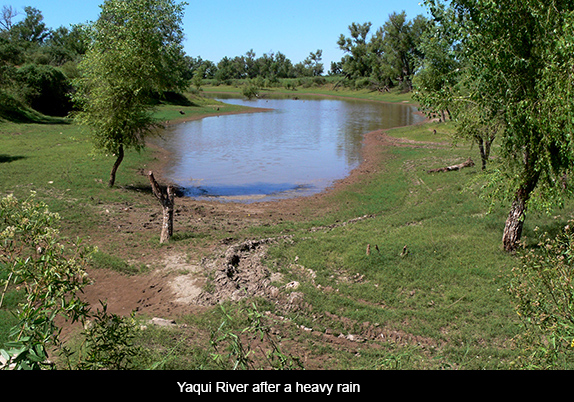

Despite the size and importance of the Yaqui River, finding the river in southern Sonora is a challenge -- even with a map in hand.

To locate the Yaqui River, you need to ask directions. The problem is not that the Río Yaqui is an ephemeral stream that flows only after the monsoon rains of the summer or the winter rains. The difficulty is that the river has disappeared.

The river is a victim of the success of Sonora’s hydraulic society. No more destructive flooding, and a reliable, year-round supply of irrigation water channeled to agribusiness in hundreds of kilometers of irrigation canals and ditches. This irrigation schematic has permitted agribusiness to cultivate not just the former river delta but also the desert scrublands that lie far outside the river’s traditional floodplain.

Only after exceptionally heavy rains does the long-dead river channel contain any water. Damming and diverting the Yaqui River has given rise to Sonora’s most productive agricultural region. But the river itself has disappeared. No longer does it flow by Yaqui villages and westward to the sea.

River Gave Life to Yaquis and Missions

When Jesuits began establishing their missions in the Yaqui Valley from 1614-1620, they found about 30,000 Yaquis living in hundreds of rancherías (hamlets) scattered throughout the valley. However, most Yaquis – who had then had multiple identities as farmers, hunter/gatherers, and fisher people – made their homes by the floodplain of the Yaqui River. The monsoon floods and late winter floods provided, during the best of years, sufficient water for two annual crops.

Along the river the Jesuits established eight missions, gathering together the Yaquis from the dispersed rancherías into what became Yaqui villages. To this day, the Yaqui people refer to these “ocho pueblos” as the centers of their culture and governance. But like the river itself, most of these towns are now ghosts of a former era. Only three of the original eight mission settlements – Pótam, Vícam, and Torim – have retained their integrity as Yaqui pueblos.

The Jesuit mission churches still stand at the center of the other five mission towns – Cócorit, Bácum, Huilbiris, Rahum, and Pitaya or Belém. But some like Cócorit have become largely mestizo towns, while others have suffered from varying degrees of depopulation.

The river-based subsistence economies of these towns have dried up and died, just like the river. Although the mission church still marks Belém as one of the eight Jesuit missions, lack of water has turned the old mission into a ghost town.[1]

Vícam and the Lost River

Traveling through Yaqui territory from Guaymas south to Ciudad Obregón, you won’t pass through any of these eight Yaqui towns.

The major modern desert cities of western Sonora – Hermosillo, Ciudad Obregón, and Guaymas – developed along the highway and railroad. But the Jesuits established their missions during an era before highways or railroads.

Even the wagon road that headed north from Sinaloa didn’t pass through the part of the Yaqui Valley with the most rancherías. Rather than establishing their new missions along the wagon road, the Jesuits built their missions on the naturally formed river levees where the Yaquis lived.

Estación Vícam is a road-stop that straddles the four-lane federal highway that connects the U.S. Southwest with all parts south in Mexico. It is here where the Yaquis since 2010 have held their community meetings about the Novillo-Hermosillo aqueduct. Estación Vícam is a product of a south-north transportation route inter-state and international commerce: wagon road, highway, and railway. It is here that the Yaquis have mounted intermittent blockades of highway traffic to express their opposition to the aqueduct that is transferring water from the Yaqui River to solve the water crisis in Hermosillo.

Intersecting Highway #15 is a two-lane road that leads west to Vícam, the cabecera or traditional seat of governance and religion authority of the Yaquis. Heading west you leave the uncultivated desert shrub lands and immediately drive into the Yaqui delta – the place where the Green Revolution in hybrid crops, mainly wheat, got its start in the 1940s and 1950s.

Since the late 1890s, the Yaqui Valley has been Sonora’s leading agribusiness region – farmed and controlled not by Yaquis but by foreign investors, the local non-indigenous or ladino agricultural elite, and a powerful community of rentistas (those who profit by renting land) who are associated with valley’s two irrigation districts.

Crop dusters circle and dive down, skimming the richly watered fields of wheat, alfalfa, and agro-export crops as they spray their load of pesticides. Irrigation canals crisscross the valley, carrying water from the Oviáchic or Álvaro Obregón dam/reservoir, which captures the flow of the Yaqui River 40 kilometers from Ciudad Obregón. The main irrigation canal – named after President Lázaro Cárdenas – is the acequia madre of the valley, skirting the east side of the Yaqui towns of Vícam and Pótam.

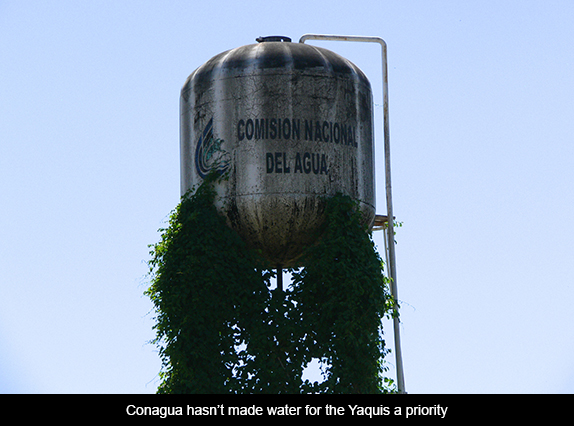

My map showed that the Yaqui River also passes immediately to the east of Vícam. But, seeing the bell towers of the old Jesuit mission and the dilapidated Conagua (National Water Commission) water tower as I entered the village, I knew that somehow I had missed the Yaqui River.

The town has no sign with its name and population, and the river is missing both a name sign and water.

Turning off the road toward the expansive plaza in front of the mission, I hailed a young man – the only person in sight – and asked if this was indeed was Vícam and, if so, where could I find the river. Eyes glazed and dulled by drugs, he held his hand out, asking for 50 pesos. He couldn’t remember where the river was.

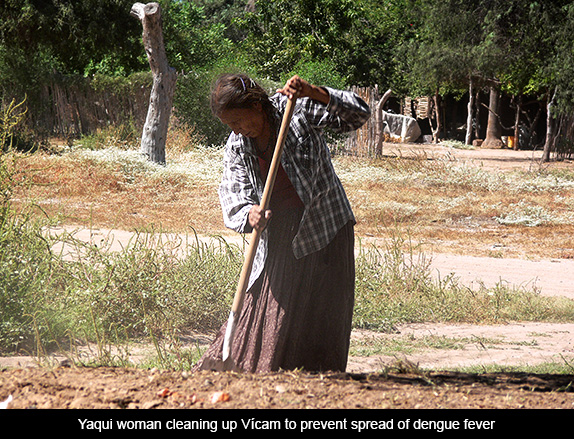

A deeply wrinkled middle-aged woman was raking up the leaves, branches, and other debris around large acacia tree in front of the deserted comisariado (local police station). Getting out of the car, I explained that I came to the land of the Yaquis as part of a research and book project about the water crisis in the U.S. and Mexican borderland states.

But before asking her how I could find the Yaqui River, I was curious about a why she was raking and sweeping the dusty ground.

“They told me to clean up here to keep dengue from spreading,” Silvia Jacarít Cupíz explained, referring to the male caciques of Vícam. Dengue – a tropical disease similar to malaria – was spreading through southern and central Sonora in October 2014 -- apparently a consequence of recent heavy rains. “We’re hungry in this village, but they don’t pay us for this work,” she lamented.

As she continued raking the dirt and gathering up the mostly organic debris into piles, she told me that I had indeed missed the river on the way into town. “But it hasn’t flowed in very long time, maybe four decades or more,” she said. Furthermore, “When we were children, the river still flowed and life was better.”

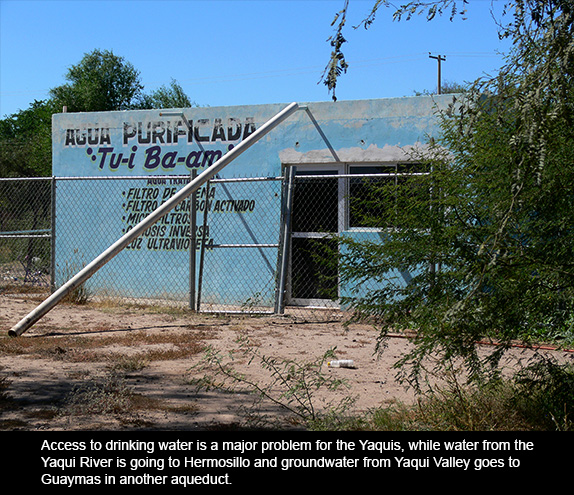

“Water is the problem here, and food too. Our life in Vícam changed when the river stopped running,” she offered. While water still passes by the town in irrigation ditches, it goes to farms that Yaquis don’t control.

It is the same account one hears from many Yaquis – a story of the Yaquis loss of connection with the river and the land that scholars have documented. “In Yaqui pueblos, being farmworkers (“jornaleros agrícolas”) on their own land continues to be one of the main jobs for the Yaquis, followed by work as ranch hands, carboneros, and fishermen.”[2] Another report by researchers from the Colegio de Sonora noted: “Almost all of the lands of the irrigation district that the Yaqui community owns are rented generally by Sonoran agricultural entrepreneurs.”[3]

“Yes, we have now water pipes connected to our homes. But the water stinks (apestosa) so we can’t drink it,” continued Jacarít. As evidence of the government’s lack of attention to the basic needs of the Yaquis, she pointed to the rusted and vine-covered Conagua water tower and to the building that is the source for the town’s purified water– both in a grave state of disrepair and abandonment.

For food, she explained that she relies on the meager income her son makes working as a carbonero, which, she explained, entails going out to the scrublands, cutting mesquite, and then turning the gathered wood into charcoal. “He comes home covered in soot, black all over. Terrible work, but there are no other options for us,” she concluded.

In the Yaqui Valley, the Old Sonora and the New Sonora live side by side. It is this contrast – between income, access to water, control of land, and living conditions – that is the context for the Yaqui water war.

It is a war, likely the first of many in Sonora, which pits the Yaquis against the state government’s new water megaprojects – a showdown between the old and new Sonoras.

[1] The eight pueblos initially all had names in the Yaqui language. Some like Vícam are derivations of the original name, in this case Bikam. Some, like Pótam, retain their original name. In the case of Belém or Pitaya, the original Yaqui name (Béene) has faded into the past.

[2] Luque , Diana et al, “Política ambiental y territories indígenas de Sonora,” Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, Marzo 2012, p. 273.

[3] Luque, Diana et al, “Pueblos indígenas de Sonora: el agua, ¿es de todos? Región y Sociedad, Número especial 3, 2012.

Responses to “River Runs Through It”