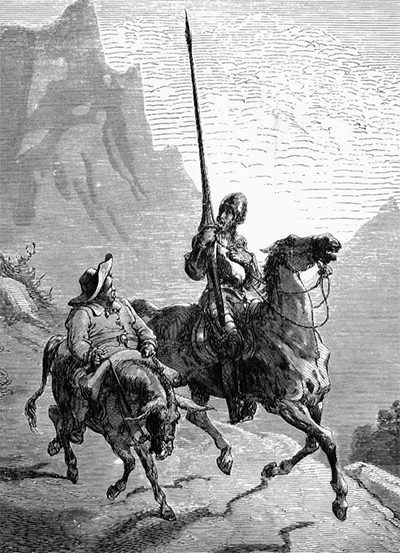

A colleague sent an email telling me that the Interstate Stream Commission was going to hold a meeting of its regional planners to begin updating their - and the state’s - water plan. I decided to attend, ever the Quixote-like student of water, this time inspired by Santa Fe’s Las Posadas procession to see if this might be the manger where new water policy would be born.

So on December 17th, I saddled up my four-wheeled Rocinante and rode south to the headquarters of the Interstate Stream Commission and the Office of the State Engineer in Albuquerque. I don’t know what I expected, not a water fountain in the lobby for sure, but the building looks like a chain motel on the outside with a government minimalist interior. The secret bathroom door code posted for our convenience in the conference room had more digits than I could remember by the time I found it. I guess you’d want high security for a “water closet” in that building.

When I registered, I wrote my full name on the tag and slapped it on my chest. But then as the afternoon wore on, I noticed that everyone I saw in the room had only written their first name. That was the first sign that I might have picked the right event to find what I’ve been looking for—a group of water people with different backgrounds and interests who talk with each other, not just socially, but with a long history of working on the big question for New Mexico, how do we share not enough water?

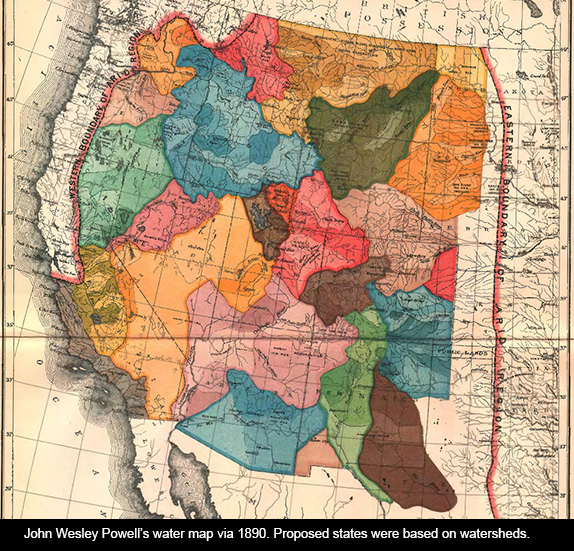

The host, the Interstate Stream Commission, ISC for short, was founded in 1935. The Office of the State Engineer had been around for a while, but the ISC took on the new job of handling the inconvenient fact that New Mexico water came from and went to other states. John Wesley Powell had warned in his report to Congress in 1890, “You better chop up the West along river basin lines,” I imagine him saying, “otherwise you‘re going to have a political nightmare over water sharing between the states.” Congress didn’t follow his advice. It didn’t like facts back then, either. Here’s one rendition of his proposed map:

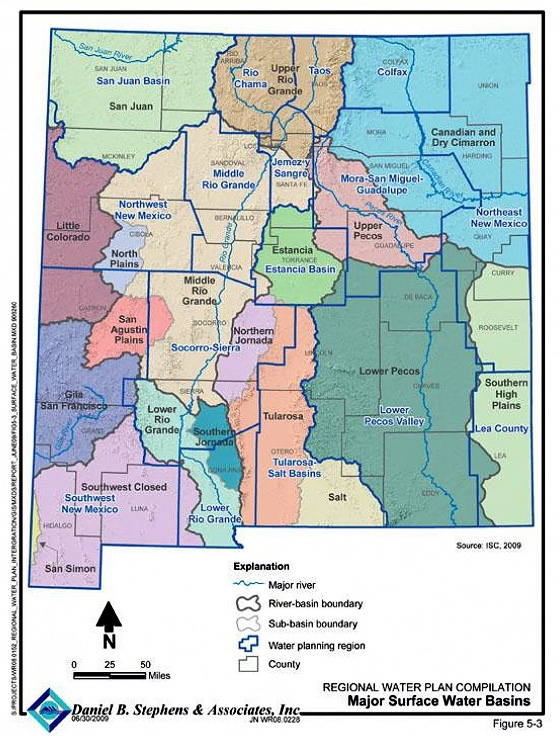

One of the nightmares that Powell predicted happened in the 1980s. El Paso wanted some underground water that straddled the Texas/New Mexico border. New Mexico said no. Texas sued. The Supreme Court told New Mexico it couldn’t say no unless it had a good reason, and right then it had none, not documented, except that it was really annoyed with Texas. For a change. So New Mexico came up with a plan to have reasons why it couldn’t give up its water, ready to lay on the table when they needed them. The plan involved setting up regions in the state, as much as possible around river basins--Powell laughing in his grave--so each basin could know about supply and demand and the gap between the two. In fact, the first manual produced for the regions in 1994 is up front with the advice—Get this right because it might have to stand up in court.

So that’s how an “interstate” commission came to run “intrastate” planning. It all makes sense if you’ve been to law school. I’ve learned that when you lift the lid off a water issue and look inside, it’s pretty much court cases all the way down.

That first regional planning effort was a little rocky. As two leaders of the project put it in a presentation, “We were given a difficult task, a short time to complete it, and no budget.” Regional planning reports came in over the next several years. I read the Jemez y Sangre plan, since I live in Santa Fe County. It is dated March, 2003. It’s pretty good, if I do say so, and it helped with a future that included the Buckman diversion and Santa Fe city’s current status as a poster child for urban water conservation in the U.S.

But now, in December of 2013, it’s time to update the plans with Regional Planning II, The Sequel (See Sigmund Silber’s piece in the Santa Fe Reporter, from which this region map is taken).

The legislature, like the governor, and like more and more people in New Mexico who think about water at all, are rushing from different directions towards the same tipping point. We have a long-range water problem, a fact about which we’ve been in a clinical state of denial, and now we had better pay attention to and plan for it. So the legislature gave $400 thousand to the ISC to update the regional plans. The Water Trust Fund—too much to explain in a brief article if you’re not familiar with it—tossed in another $400 thousand. It sounds like a lot, but remember the old quote from U.S. Senator Dirksen, “A billion here, a billion there, pretty soon you’re talking about real money.”

What does the legislature want for their money? A documented analysis of supply and demand in each region, a projection of how future use might change, and a plan for what to do about it. That’s all.

The first part of the job shouldn’t be too bad. ISC will provide each region with an estimate of supply based on water use reported to the Office of the State Engineer. The Bureau of Business and Economic Research from UNM will provide the demand estimates. Each region will take that data and decide whether there is enough supply to meet the demand. There won’t be. Everyone already knows that.

During the meeting, regional people made it clear that they will add a few things they know about their context that the ISC won’t provide, like evaporation and pre-1907 use and domestic wells. But the conclusion is inevitable: In our region, each regional planning committee will more or less say, the ISC/Bureau data look bad, but it’s even worse than that here on the ground. Case closed. Badabing Badaboom, as Tony Soprano used to say.

The interesting—and time-consuming--job for the regions will be to come up with ideas of how to bring supply and demand into balance. Here the experience and creativity at the Albuquerque meeting spilled over the time limit and could have gone on for hours more. Here is where I see some opportunities that the current guidelines aren’t taking advantage of.

The previous Jemez y Sangre plan—the plan I actually read—already laid out strategies, most of which never made it from paper into reality, most of which still apply to the current situation. Conversations during the meeting make it a good bet that most other plans are the same story.

Asking each region to independently come up with yet another laundry list of strategies, many if not most of which would just repeat the earlier work—why not figure a better way to use all that knowledge and passion about water to work on it collectively and in a more focused way and produce a coherent state-wide strategy for changes in water governance? Of course different regions would differ in emphasis and details, but why not produce a kind of “theme and variations” document, a few general “themes” for the state level, “variations” for the regions, or in some cases, sub-regions.

That would change the rules for the new planning strategy. It would also be more efficient, an issue at the meeting since the ISC laid out an aggressive time schedule and regional people have day jobs. Regions wouldn’t just sit in the privacy of their own basin and write their separate lists. They’d propose the overall strategy that the state so desperately needs. There are plenty of organizational-communication methods out there for doing this kind of thing, as well as plenty of digital ways to facilitate it. Some face-to-face gatherings would be important as well. Dios sabe that I’m no expert here, but I’ve been part of processes like this several times and they can work for a group with a lot of shared background knowledge and a commitment to solve a common problem. That’s the kind of group the people at the meeting with their first-name-only name tags represented. They didn’t all agree. No one sang “Michael Row the Boat Ashore.” But they were willing to talk things over.

The final part of the planning job that ISC requested is the hardest and the one where the most frustration spilled out. The earlier reports contained good ideas. Most of them were never brought to life. What is the point of doing it again? Is something different now? Is there a political will to put a plan to use?

The Governor just promised two million for water work. Senator Udall recently sponsored two statewide water conferences. The legislature talked more about water than ever before in their last session and my representatives say they’re poised for action. The State Engineer is trying to figure out how to use the new “adaptive” management. My county just appointed its first water advisory panel. Media coverage of state water issues is more and more frequent, or so it seems to me. I’d have to retire to have enough time to keep up with all the water events going on around the state. Clearly there is at least the appearance of political will to change water governance.

But where is its center of gravity? How does the process of producing new regional water planning documents fit in? Is it just another call for paper, doomed—like so many reports in my experience—to a press release and a long and peaceful shelf afterlife? Or is it really an effort to empower people from all over the state who know water and how to talk with—and listen to—each other, people who can collectively come up with strategies to respond to a problem we know has already arrived?

People involved in the new regional planning effort need to know that their work has a fair chance of helping the state into the evidence-based and reality-oriented water governance reform that has so far eluded us. During the meeting there was some discussion of whether the planning should be “top down” or “bottom up.” For a few hours there, though, it seemed to me that both were working together in the same conversation. But where is the commitment to put the plan to work when they’re finished?

A historian of business, Alfred Chandler, is famous for his saying about change, that structure has to follow strategy. We all know that we need a new water strategy. The planning meeting at the ISC in Albuquerque felt like a structure different from the gatherings I’ve seen in my water quest so far. A new structure born of a long history of personal relationships around water might breed a new strategy trying to get out? Sounds like New Mexico to me. The regional planning effort might be a chance to let it grow and make it clear. But even if that guess has something to it, where is the political commitment to use it? Governor? Legislators? Anyone out there?

I told Rocinante about the gathering on the ride home. “Damn, what if it wasn’t a windmill,” he said.

Responses to “Regional Water Planning - Just Another Windmill?”