I was listening to our vice president mouthing off to the Russians about not permitting one country to simply take over another, and all I can think is, what hypocrisy! The United States is the champion of starting wars, then collecting the spoils.

As I watched the VP, I flashed back to when we precipitated the Spanish-American War. The United States has not altered its face, the one it shows to the world, since the turn of the 20th Century. The thinking that precipitated the Spanish-American War, undeniably, was in evidence some years before, but only in non-official, jingoistic groups. As the 1800s turned over, imperialist motives were generated by the men who by that time were in near total control of the nation, the Super Capitalists. Grover Cleveland was the last man in the White House to decry expansion, invoking Jefferson’s ironic comment:

"If there is one principle more deeply rooted in the mind of every American, it is that we should have nothing to do with conquest."

And Thomas Reed (R-Maine), the imposing Speaker of the House of Representatives, perhaps the last “idealist” in American government, when speaking out against expansive colonialism, was almost alone. Reed, a friend to Grover Cleveland, was one of the most powerful men in the history of our nation’s politics—but he was a cut above the petty power plays and frauds that go on today. Barbara Tuchman, in The Proud Tower (from a poem by E.A. Poe: And from a proud tower in the town/Death looks gigantically down) says, while speaking about the presidential nominations of 1892, “Reed would not go out of his way to build up support for himself by the usual methods...When the railroad magnate Collis P Huntington, of the Southern Pacific, three times asked to see Reed’s campaign manager...Reed said yes, ‘But remember, not one dollar from Mr. Huntington for my campaign fund!’”

This integrity in the face of corruption must have been galling to the vultures that infested “the people’s seat of government”; today, it is virtually unheard of—in any way, shape or form.

Reed never made it, as Tuchman explains.

“The death of the silent quorum* (which Reed instituted; the rules of the House became known as Reed’s Rules) was discussed in parliamentary bodies all over the world. At home it made Reed a leading political figure and obvious candidate for the presidential nomination of 1896. But his time had not yet come, as he correctly judged, for when asked if he thought his party would nominate him, he replied, ‘They might do worse, and I think they will.’” The Republicans nominated McKinley.

His cynicism was just, especially in the teeth of the insanity that was all about. For on February 24, 1895, the Cuban people rose up against Spain. On March 8, a Spanish gunboat fired on an American merchant vessel. Senator Morgan, a democrat from Alabama, aired his view, a view, as Tuchman observes, very close to majority thinking in America:

“Cuba should become an American colony.”

The Republicans were no less adamant. Senator Cullom of Illinois:

“It is time some one woke up and realized the necessity of annexing some property – we want all this northern hemisphere”

After Cuba? The Philippines. And to protect interests in the Pacific, Hawaii was the next logical step. As President McKinley said:

“We need Hawaii just as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is Manifest Destiny.”

Reed fought this empire building almost alone.

The Nation wrote:

“Courage to oppose a popular mania, above all to go against party, is not so common a political virtue that we can afford not to pay our tribute to the man who exhibits it.”

In Hawaii’s case, Queen Lili‘uokalani didn’t have a navy, so it was no contest. (Read about the Battle of Moʻiliʻili in 1895.)

Hawaii was annexed July 7, 1898.

February of 1899 Reed resigned from government. Again Tuchman:

“Reed himself offered no public explanation of his going except to say, in a farewell letter to his constituents in Maine, ‘Office as a ribbon to stick in your coat is worth no-one’s consideration.’ Cornered in the Manhattan Hotel in New York by reporters who urged that the public would want to hear from him, he replied, ‘The public! I have no interest in the public,’ and turned on his heel and walked away.”

The realities of Reed’s world tend to overshadow his work in government. What made him quit, it seems to me, was not the war with Spain, nor the jingoism of Hearst and associates, not even the butchery perpetrated against the People’s Revolutionaries in the Philippines—it was American stupidity and lethargy. The masses that changed with the whims of their popular leaders. This stupidity, nurtured and force-fed for the past century, has now become something far worse, a far more compounded disease: the mass media and the plutocrats have done their work well.

As far as Reed was concerned, or any other person who labors for the betterment of his fellow citizens, let Jonathan Swift’s epitaph suffice:

He gave the little wealth he had

To build a house for Fools and Mad.

* The Silent Quorum was a loophole in House rules that allowed a member to sit at his seat but by not answering the role call—remaining silent—he would not be counted “Present” which on that day, might lead to a quorum so that a vote could be taken.

Not answering was a way to stymie the opposition.

One day Reed began the roll call and when members who were present refused to answer, Reed directed the Clerk to count them as present. When one Democrat from Kentucky challenged Reed’s authority to count him present, Reed answered by saying “The Chair is making a statement of fact that the gentleman from Kentucky is present. Does he deny it?”

Pandemonium broke out on a run as Democrats tried to flee, but Reed had locked the doors. They were all counted. Protests continued for days, but eventually this technicality was eliminated and Reed’s Rules were installed permanently.

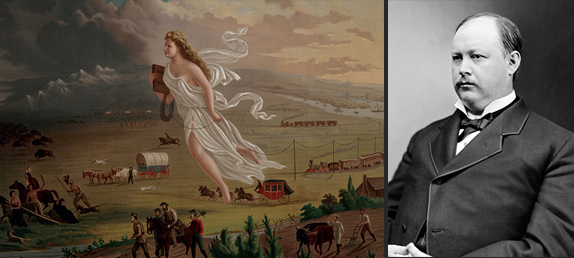

(Photo of “Westward: The Course of Destiny” by J.D. Thomas. Original created in 1873 by George A. Crofutt based on an 1872 painting of the same title by John Gast.)

Responses to “Reed’s Rules & the Drive to Create Colonies”