This year the state Department of Tourism is spending $8.6 million on ads, but some publicity is so valuable it can’t be bought at any price. Such is the case with the New Yorker’s just over 1 million subscribers and Rolling Stone’s nearly 1.5 million. However, without the Martinez administration spending a single cent, New Mexico just scored major feature articles (totaling some 15,000 words) in both magazines in the same week.

Unfortunately, all this publicity, although free, is hardly what any advertiser would want. Both articles focused on the rampage of violence by the Albuquerque Police Department, the U.S. Department of Justice investigation and the roots of probably the biggest scandal in Albuquerque history.

The damage to New Mexico’s dominant city is incalculable. One letter writer told Rolling Stone, “If you live in Albuquerque, for the love of God, consider relocating.” Another reader replied, “I do live in Albuquerque. Also, everyone does want to relocate, but they call this the ‘Land of Entrapment’ for a reason. This city is becoming the new Juarez. Thank you for your sympathy though.”

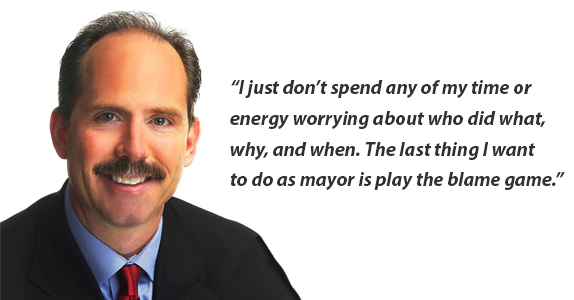

While some reactions may be overwrought, others are decidedly understated, particularly this statement to the New Yorker by Albuquerque Mayor Richard J. Berry. Commenting on the department that consumes the largest share of his budget, accounts for the biggest percentage of his employees and is his direct legal and political responsibility, he said, “I just don’t spend any of my time or energy worrying about who did what, why, and when. The last thing I want to do as mayor is play the blame game.” But if the guy ultimately responsible for APD doesn’t want to know what went wrong and why, how in the world is he going to fix it?

Part of the answer may be that although the Justice Department harshly criticized APD’s “unconstitutional use of excessive force,” the mayor does not sound as if he is convinced. As recently as July 2011, only a year before the Justice Department launched its probe, he called APD one of the finest police forces in the country.

Perhaps the mayor’s problem is that he is getting all his information from his police chiefs, none of whom has indicated any awareness of their underlings misbehavior. The previous boss, Chief Ray Schultz, told his officers after the Justice Department announced its investigation in 2012, “Most likely the DOJ will find that APD has its house in order….Have your officers stand tall and be proud to be part of our great department.” But the New Yorker noted that of the 15 Justice Department investigations of police departments in the past four years, the report on APD was “arguably the most disparaging.”

Schultz’s replacement, Chief Gorden Eden, hasn’t displayed a great deal more sensitivity. In fact, he seems to have done all in his power to keep the feds from getting to the bottom of the problem. Last June he emailed his officers, "NO one is to meet with DOJ—no one!! DOJ and its representatives have held several meetings with APD officers. This is a CRITICAL MATTER! No One. Make it clear to everyone, it’s got to stop immediately.”

Eden is not the only one to be defensive. A few days ago a policeman tweeted a poem that included these lines:

I know things are bad and dangerous

And many people hate the police and cuss….

It is not fair to the police in any way,

I hope it can soon be a better day.

It is significant that the Justice Department not only excoriated police shootings but also found nonlethal types of police violence, such as the use of tasers, to be excessive and unjustified.

Much of the two long magazine articles focused on incidents that have been previously reported, either by the Department of Justice or local media. But what the pieces did, that our own media has failed to do, was connect the dots. They looked at the history of police violence and tried to squirrel out the causes and origins. Several important themes emerged.

The problem did not start with Chief Eden or even with Mayor Barry. A big piece of it goes back to Mayor Marty Chavez’s 2005 campaign for reelection when he promised to increase APD to 1,000 officers. Both articles quote a number of former officers (no one has been able to find whistle blowers currently on the force) as saying standards were lowered to facilitate massive recruitment, with disastrous results.

In addition, Rolling Stone reported a key incident from the same time:

“In 2005, officers Richard Smith and Michael King were killed in the line of duty by a man they were picking up for a mental-health evaluation. King had been an academy classmate of Police Chief Ray Schultz, who, in a tearful press conference after the killings, called it ‘one of the saddest days in the history of the Albuquerque Police Department.’ Inside the department, former officers say, the deaths were a turning point: Officer safety became the order of the day.”

Although neither article made much of it, Darren White’s sojourn as director of public safety at the start of the Berry administration, more or less supplanting the authority of everyone—the police chief, the chief administrative officer and the mayor himself—also gave police a signal that the gloves were off.

Another fact that could be related to the cops’ proclivity to shoot quickly and fatally is the increased armaments of the suspects they encounter. With gun laws growing even more lax and new laws permitting concealed weapons, it is not illogical for police to assume that everyone they encounter is locked and loaded.

Almost everyone who has looked at the problem, including the mayor, has also pinpointed the lack of resources to help the seriously mentally ill. All too often, the police become the first line of treatment for mental illness, and they are untrained and ill-equipped to do the job.

Still another factor is the absence of oversight, by everyone—the media, the politicians, the district attorney and the public. As police violence snowballed, only the victims’ families complained, and most of the victims were poor, homeless or mentally disturbed.

One consultant asked to examine police misconduct described the hostility of the mayor and city councilors to his critique. There are indications the police maintained a solid blue wall that intimidated dissidents in their own ranks and stopped them from exposing misbehavior.

Local probes of police misconduct relied largely on internal investigations by the police themselves. Normal grand juries were not impaneled in cases of police violence until 2013. Until then, “special invesitgative grand juries” were the only available forum, and they were not allowed to issue indictments. The practice was stopped only after a judge demanded it.

Enforcing the law against the police is the job of the district attorney. But Kari Brandenburg, who until last month had never pursued criminal charges against a policeman (she has now moved against two cops for shooting James Boyd, who was illegally camping in the Sandia Mountain foothills) admitted in a fascinating interview with KOAT-TV:

“I've had my eyes opened, no question, in the last couple of months. Is that wrong? That it took the last couple of months to open my eyes? Probably. I was so busy doing my job here I wasn't noticing a lot of bigger issues and a lot of bigger problems in our community. Well, I'm awake now."

Brandenburg added, “I don’t think we have courageous leadership in the police department. It breaks my heart, because I know there was a time when we did have courageous leadership.”

The media has been equally absent without leave. It is noteworthy that both the New Yorker and Rolling Stone could find only one local reporter who had dug into police misconduct, Jeff Proctor, who left the Albuquerque Journal for KRQE-TV.

Finally, and perhaps most important, the public. The New Yorker focuses heavily on the case of Christopher Torres, a schizophrenic who was shot to death in his own backyard while two out-of-uniform policeman were trying to serve a warrant from a two-month-old road rage incident. The notable aspect of the Torres case was that unlike almost every other police shooting victim, he lived in a prosperous area of the West Mesa and his parents were successful middle class professionals—his father a lawyer and his mother head of county human services.

This case, which resulted in a judge slamming APD with a $6 million fine (later reduced), and the Boyd shooting in the Sandias seem to have done what dozens of other shootings failed to do: mobilize public anxiety about what its police department is up to.

Now with the national media watching, the public paying attention, the district attorney opening her eyes, and the federal government looking over its shoulder, APD may see real change for the first time. At least many hope so.

Responses to “Publicity from Hell”