The Plight of the Part-Timer in American Universities

It’s hard to imagine that close to half the teachers in American colleges and universities belong to a caste of economic serfs, most of them with advanced degrees, and many of those with Ph.D’s but no tenure and no possibility of full-time work with benefits. And in community colleges around the country, the serf caste often makes up well over half the teachers.

Schools will admit this is a money saving proposition. And boy is money being saved! Well published, full-time tenured faculty are the backbone of any university, and they earn their keep. I’m not writing this to make them look bad.

But administrators can get an M.A. or Ph.D. serf to teach a class for a mere $3000 at UNM or even $2500 at CNM. If that person should teach say four classes a year at $3,000, that’s $12,000, with no benefits, no perks, no nada. This is chump change when you contrast that with the $65,000 to $125,000 or so for the low to moderately paid tenure-track or tenured profs with all the benefits and perks. You can clearly see the economic advantage to universities of using part-time teaching serfs.

Interestingly, this doesn’t tend to lower the level of instruction or compromise learning. In fact, students tend to take part-timer’s classes more than the tenured profs, a recent national survey showed. This is probably because part-timers really do teach for the love of it, even if they are teaching it for an hourly wage that’s far less than mechanics and plumbers charge, no offense to those needed and honorable professions intended.

The problem is that part-time teachers, despite their love of teaching and their excellent care of students, are part of America’s working poor. But they are highly educated, probably debt ridden, scholars and sometimes very well published in their fields. These are experts who are forced by circumstances to sometimes teach five or six classes a semester to make a meager living.

Here’s how bad it gets. If you’re teaching a class of 17 people, which would be a packed seminar, and the class runs 16 weeks for 2.5 hours each with all the prep time, the student conferences, the paper grading and note writing, the student evaluations, and the faculty meetings, you’d be lucky to make $12 to $15 an hour, if you’re doing your job the way it should be done. Add more students and you lower the hourly wage.

This is what many scholars can expect to make with an advanced degree and all the years of work that takes to achieve – and the massive debt – in a glutted market in which colleges and universities increasingly use a corporate model of operation with astronomical salaries at the top and low paid graduate students and part-timers, perilously close to unpaid interns, at the bottom. And that’s not to mention the vast salaries for what amounts to public relations jobs in the Athletic Department.

Pay scales vary at different schools. One Ivy League school I know of has paid authors $10,000 to teach one writing seminar. But UNM is not in the Ivy League.

Nationally “part-time/adjunct faculty account for 47 percent of all faculty, not including graduate employees. The percentage is even higher in community colleges, with part-time/adjunct faculty representing nearly 70 percent of the instructional workforce of those institutions,” according to a 2010 national survey conducted by the American Federation of Teachers, “A Union of Professionals.”

UNM’s Main Campus, as it happens, has far fewer part-time instructors than the national average at 34 percent. That’s 506 part-timers out of 1,455 instructional employees, according to collegefactual.com – which comments that this “could be indicative of University of New Mexico-Main Campus’s commitment to building a strong, long-term instructional team.” But 34 percent is still more than a one third of the school’s teachers.

“Colleges often use part-time professors and adjuncts to teach courses, rather than full-time faculty. This hiring practice is primarily a way to save money amid increasingly tight budgets, however, it is a controversial practice with strong views on both sides,” says collegefactual.com.

As a longtime part-timer myself at UNM, I know that my colleagues who aren’t tenure track do great teaching. Their students and student evaluations speak to their conscientiousness, their knowledge, and their professionalism.

But what does it say about a nation’s values that often nearly half of the teachers in institutions of higher learning can’t make a living at what they were educated to do over many years, and what they do with comparable success to teachers who not only make a living, but are very well compensated while the serf caste at their schools is barely scraping along.

In a just world, these conditions would be scandalous. In the present state of our national educational culture, they are largely invisible, or off-handedly dismissed with a “gee I’m sorry” look, and are certainly never talked about in a serious way.

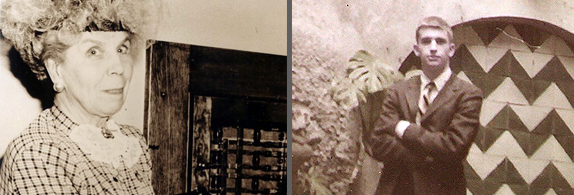

Erna Fergusson

I met Erna Fergusson in l961 or 1962. The Albuquerque-born painter Leonard Wood took me to meet the famous lady and arch champion of New Mexico at her home on Rio Grande Boulevard. What she thought of a couple of scraggly boys wanting to make her acquaintance, I’m not sure. But she was gracious and warm, and said witty things from her chaise lounge, and served us tea laced with rum, and rum cakes too. She seemed very grand and very down-to-earth at the same time. She talked about New Mexico in a direct, poetic way I’d never heard before.

The next day I went to the library to see who Erna Fergusson was. And I learned that she was synonymous with an attitude and a vision of New Mexico and the Southwest as an enchanted place. I recognized right way what she was talking about, as have tens of thousands of her avid readers. Her love of this place gave voice to our own. She wrote about New Mexico in away that made people feel proud of their own feelings and realizations. A native Anglo New Mexican, the granddaughter of Franz Huning and child of Harvey Fergusson and Clara Mary Huning, Erna Fergusson was a child of founding families in Albuquerque, but she re-created herself through her writings, and used the access afforded by her lineage to explain, describe and extoll the often mysterious and foreign-seeming world of her home state to outsiders.

It was in WWI that Fergusson first realized her fascination for New Mexico. During the war, she joined the Red Cross as the “Home Service Secretary and State Supervisor for New Mexico,” according to a handsome brief biography by Michael Ann Sullivan written for the New Mexico Office of the State Historian.

“She spoke Spanish fluently and traveled to remote villages and towns across the state helping the families of soldiers. She described her work as ‘…fixing things up for soldiers who had enlisted under a couple of names, for mothers who asked me what the ocean was, and for wives who had forgotten to marry.’ In later years,” Sullivan continues, “she claimed this experience as the first realization that New Mexico was ‘a very wonderful state to belong to.’”

If anyone stands out as the creator of the image of the Southwest as a singularly magnificent place Erna Fergusson has to be near the top of the ladder. Not many are familiar with her now, even though there’s a public library named in her honor in Albuquerque. The UNM Alumni Association gives an Erna Fergusson award for service. And Fergusson was given an Honorary Doctorate of Letters from the University of New Mexico in l943, a rare tribute for a non-academic.

Fergusson was a writer’s writer. The author of 14 books, many of them profoundly influential in keeping New Mexico’s economy healthy and in line with the integrity of its cultural uniqueness and the unparalleled beauty of its landscape, she worked in the l920’s as a writer and columnist for the Albuquerque Herald, writing about her home town, and published pieces on New Mexico in New York’s Century Magazine before it folded in l930. It was in New York that she interested the publisher Alfred Knopf in New Mexico. The prestige of having her books in the hands of a major East Coast publisher gave her not only a wide audience, but made her famous around the country and in her home state.

In her youth she was a Harvey Girl working for the Fred Harvey chain of railroad restaurants and hotels. Later she ran a famous tour of “Indian Country” called Koshare Tours, which was bought up by the Fred Harvey organization, with her still at the helm, and renamed the “Indian Detour Service.”

Her books Dancing Gods, published in l931, her Our Southwest, l940, and New Mexico: A pageant of Three Peoples, l951, all published by Knopf, made her the major popularizer of the idea of New Mexico’s cultural pluralism and the tolerance that went with it.

In New Mexico: A Pageant of Three Peoples, Fergusson took up the long struggle between New Mexico and Texas with a particular ferocity. Ever the defender of our state, she railed against the prejudices of the Confederacy that she saw moving in with “tejanos.” She wrote about the lingering influence of KKK values moving up from Texas in the l930s and the Klan’s eventual demise here. “So the Klan passed,” she wrote, “but the fanaticism it highlighted did not. In every political campaign somebody makes a loose remark about ‘keeping this a white man’s state,’ meaning a state of prejudice.”

“Like every fight for decency,” she wrote, “New Mexico’s fight is slow, often discouraging. The question is always there: will these ignorant newcomers overwhelm us before we can teach them to appreciate New Mexico’s fine tradition of tolerance? As prejudice is always founded on ignorance, and as ignorance can be cured, New Mexico may succeed in eradicating the ‘tejano’ mores and in developing along its own traditional lines.”

When I met Erna Fergusson, she was two years from her death. At the time I had no idea who she was, beyond that of being an important person. My admiration for her has grown with every book of hers I’ve read. It is the fate of all writers to become “dated” and dismissed by those expressing a more nuanced and modern perspective. But Erna Fergusson’s humanitarian passions, and her status as a master appreciator of New Mexico and its people, are an invisible bedrock for tolerance and intercultural communication and understanding to this day. Her work deserves a major revival and reappraisal by contemporary thinkers and historians in her home state.

Flood Control in Chaco Canyon

When a big rainstorm hits Chaco Canyon it can send so much water cascading off the canyon walls that it looks for a moment like Niagara Falls. But Chacoans knew how to deal with flood water, or any water that came along. They could take torrents crashing onto the canyon floor from hundreds of feet up and slow the water down, gentle it, smooth it, and spread it out over long distances, so it would sink in without doing damage and give the farmers extra leeway in the dry times sure to come.

Hearing the news of floods from the recent record breaking rains experienced in Colorado and parts of New Mexico, I’m more in awe than ever of the early Pueblo water engineers. And seeing TV image of huge walls of water crashing into bridge pylons down the center of I-40 gave me an eerie sense that we might not be doing things the right way in modern Albuquerque.

Chacoan water engineers, using wooden tools and ingenuity were masters at taking the destructive force out of water, and converting it into useful movement. The pre-Pueblo peoples in the Four Corners knew the land so well they worked in partnership with it, not against it. They understood every source of water they had, from seeps and springs and canyon runoffs to torrential waters from those mighty rains that can strike us here out of the blue. Their cardinal rule, it seems to me, was never to let a drop of water go to waste. Using check dams, channels, pooling, mazes of weirs and other means, flood waters weren’t allowed to cut new arroyos into the canyon floor and empty uselessly into Chaco Wash. [See Canyon Gardens, UNM Press, edited by V.B. Price and Baker Morrow for a glimpse at water management by Puebloan peoples.]

I wonder if modern New Mexicans will, or even can, start to think like Chacoans and accommodate floods, use them productively to recharge aquifers and to make more groundcover in damaged watersheds possible. I wonder if we’ll find ways of slowing flood waters down and letting the waters sink into soil rather than just shooting them through concrete lined canals into the Rio Grande.

We know that the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District directs heavy rain waters into our ditch system. We‘ve seen lots of water in the Duranes Lateral this year, way beyond when the water was supposed to have been turned off. MRGCD ditch riders confirm the new water is from flooding rains in the north.

Even though we’re living through a long drought, we know that dryness will be punctuated by massive bursts of rain, and, at times, hurricane-like winds before the dryness returns to dominate the landscape.

It’s probably time to begin a community discussion on how to make the most out of these monsoonal floods. Many smaller communities are already starting to think about what to do. A 2003 History of Floods and Flood Problems in New Mexico produced by the New Mexico Floodplain Managers Association relates how desperate and really abandoned New Mexicans felt in the l940’s war years when no federal flood management money was forthcoming. The work that was done to control flooding of the Rio Grande some 40 years later has made life a lot smoother in Albuquerque despite the intensity of weather events brought on by rises in the temperature of the atmosphere. But floods from rain runoff are still a potentially disastrous problem, with major streets in the far northeast heights paved over old water ways and developments on the west mesa impinging on major arroyos and other water courses.

Finding ways to make new use of flood waters would require a major change in mindset. We’d have to relearn how to design with nature, not against it. We’d have to come to understand what anthropologist Keith Basso meant when he wrote that “wisdom sits in places.” Basso was an expert on the Western Apache. He understood that the Apache, like the Pueblos, knew virtually everything there was to know about where they lived, knew how the natural forces worked, and, in fact, built their spiritual lives around the patterns and anomalies of the land and weather of their specific places.

It seems likely that our powerful weather events, energized by increased atmospheric temperatures, might prove to be too much for even our advanced technologies, but perhaps not too much for modern versions of what worked in Chacoan and general Puebloan past using wood and muscle to redirect the ferocity of natural forces.

Wisdom does sit in places. The more we know about where we are, and the more we come to respect the limitations that natural realities place upon us, the more chance we have of taming flood waters, especially in water sheds, and putting them to productive use.

Critters We Have Known – Hermes Coyote

Anyone who values the trickster spirit in their lives, the grace of chance, play, and humor, and the blessings of the unexpected, sees in the coyote a psychological, if not a spiritual, companion along life’s often baffling journeys.

Supremely adaptable, opportunistic, able to take up some of the ecological slack when wolves are eradicated, reproductively exuberant, growing in population all the time, coyotes are flexible enough to flourish in cities and suburbs, fast enough to escape humans, and cunning enough to grab any morsel they can find, from pet cats and little dogs, to the leavings that bears and raccoons might like.

“Coyotl” is the Aztec word for trickster and the source of the Spanish word coyote. As a trickster, coyote is a cousin of Hermes, the Greek god of luck and thieves and boundaries, the god who takes you to the land of the dead, and who, like the Roman God Mercury, is also the winged messenger of Zeus/Jupiter. Everything agile and deft associated with the imagination, tricksters have mastered, sometimes for good, sometimes for for ill. But every time you find a piece of information that changes your life, be it a book, or free floating fact, Coyote-Hermes-Mercury, the luck bringers, are to be thanked.

It’s not easy to get to know a coyote. We’ve never had anything more than distant sightings, even ones that are as close as across a ditch. Coyotes always seem far away. And like luck, they can’t be courted. We’ve heard tales of coyotes snatching little dogs from masters and running off into the fields. But trickster coyote’s are, after all, master storytellers and inventers of tall tales.

I’m always glad to see a trickster coyote trotting along looking for a bite to eat. They’re like many of the people I feel most comfortable with – resourceful friends, self-reliant, never a whine out of them in bad times, always a laugh, always a serious effort to make the most of what has happened to them. Many painters and poets I like and trust have those qualities. One trusts tricksters to be who they are, and to be liberated from your expectations. They teach us something about freedom that’s as elusive as freedom is itself.

My most intimate moment with coyotes came after the death of my father. On a hike in the Elena Gallegoes Open Space, ringed by the Sandias, we were saying our goodbyes to dad when we heard in the twilight the coyotes taking up their song. Everywhere we listened, they were singing louder and louder as the sun sank beneath the horizon. Hermes-Coyote-Mercury was showing Dad the way. And like him, they were with us -- intimate, exhilarating, but very far away.

(All images are propety of their respective owners. Creative Comons via Flickr: Professor at chalkboard by CPS Photo Library; Chaco by Mark Byzewski; Coyote running by Margarita Ruiz)

Responses to “Provincial Matters, 9-23-2013”