Gila River, Chaco Canyon, Otero Mesa

Knowing Governor Martinez’s ties to the radical anti-government Republican Right, I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to predict that if she is re-elected she will use her influence and the covert powers of her office to both help and cajole the Bureau of Land Management in New Mexico to move ahead with her blessing to compromise, dirty up, or destroy three of New Mexico’s most treasured and pristine public spaces.

She would not stand in the way of the BLM handing out licenses to frack and drill around Chaco Culture National Historic Park, right up to the edge of the world heritage site no further than a quarter mile away.

She’d exert what pressure she could with the Interstate Stream Commission to build dams along the last wild river and riparian environment in New Mexico, the Gila River in the Gila National Wilderness, the first wilderness designation anywhere in the world, and near the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument.

And she’d do nothing to stop the BLM from pushing to permit oil and gas drilling and rare earth strip mining on the 1.2 million acres of Otero Mesa, the last great untouched Chihuahuan desert grassland environment in the United States. This huge, isolated untouched area south of Alamogordo has hundreds of species of wildlife and an aquifer reputed to have enough pure fossil water to satisfy the thirst of a million people for 100 years. That’s pretty much what parched El Paso, Las Cruces, and northern Mexico need more than anything else.

Each of these three great treasures are one of a kind. Spoil them and they’ll never return to their original perfection. And why am I so sure Governor Martinez won’t lift a hand to protect them if she’s reelected? It’s just a prediction, after all. But what we know so far about her environmental record, her inaction over water planning, her bending-over-backwards to let the copper mining industry contaminate ground water on the promise of cleaning it up later, and the general environmental phobia and loathing of the post-Nixon, Libertarian Tea Party views of her political party, it all just adds up to disaster.

Republican environmental philosophy these days views all environmental laws as a constraint on commerce. It is so starry eyed about the righteousness of the market and the moral purity of the commercial classes that it doesn’t comprehend environmental law as a way to protect workers and the rest of the public from unscrupulous business bureaucracies and corporate bandits willing to cut any corner and wreck any ecosystem to increase their profits. In fact, Republican think tanks consider the public good to be non-existent. The public doesn’t exist and only private profit matters – and private profiteers.

Damming or “diverting” the Gila River, the last un-dammed major river in New Mexico, is the kind of privatizing scheme that dismisses the commons as having no inherent value. The incredibly expensive dams, which could end up being mostly paid for by New Mexico taxpayers, will serve the interests of small farmers and business people in areas as far away as Deming, should they be built. The Gila in New Mexico is largely a wild riparian environment enjoyed by countless campers and hikers and people seeking the solitude of the wilderness. Environmental reporter Laura Paskus did a definitive piece on damming the Gila in the August 5, 2014 edition of the Santa Fe New Reporter, “Divert & Conquer: NM’s Plans to Dam the Gila River Are Dubious and Damn Expensive.” You can find it here.

The Gila River, which is dammed and controlled to the last drop in Arizona before it runs into the desert outside of Phoenix, is part of the Colorado River system and one of the reasons New Mexico has access to Colorado River water.

Its fate, here, is all locked up in the politics of the Interstate Stream Commission, many of whose leading members are Martinez appointments. The Commission must make a decision by December 31 that could release federal funds to start the engineering projects on the river.

Otero Mesa, one of New Mexico’s pristine wonders, is a sitting duck for aggressive development. Fracking and other kinds of drilling have been warded off for the moment, largely by the efforts of environmental groups and the Richardson administration, but knowing the BLM and state government’s long standing bias in favor of the oil and gas industry, anything could happen. And should rare earth mining take place at Otero, its island mountains, that are one of its most beautiful and interesting life zone areas, would be leveled and roads would scar the land. Rare earths, used in electronics, turn out not to be rare in the sense of being hard to find. They are present many places but in such thin quantities that huge amounts of earth must be moved to get at them. Otero Mesa should never be touched by machinery or motorized vehicles, much less mined. Some even say that the pure fossil water of the Salt Basin aquifer under Otero Mesa, and extending into Mexico, should not be pumped either. But that’s another discussion. In this part of the world, water trumps oil and gas drilling and rare earth mining hands down.

The Mercury has opposed fracking around Chaco Canyon from the start. We’ve advocated a no-development zone around the canyon, its ancient sites, its deep silence, and its dark, dark skies. Such a zone should be at least twenty miles out from the site, and I’d prefer to see a 50 mile no-development ring. The amount of oil and gas that could be extracted close in to Chaco could not, in anyone’s wildest dreams, result in such a vast fortune that ruining the canyon’s solitude and mysterious power forever would be financially justified. Nothing, of course would morally justify even the slightest tampering with its world-beloved environment.

But Governor Martinez’s campaigns are financed by people who care nothing for public lands, would like to auction them off, privatize them, and turn them into consumer products.

If for no other reason, the November election this year is crucial to the environmental health of our state and to the spiritual and transcendent experiences that are available to all of us, experiences that can’t be bought or sold without destroying them.

Virgil and Cato

“The noblest motive is the public good.” That’s what the Roman poet Virgil thought when he wrote of his patron the first emperor of Rome, Augustus Caesar, in his epic poem of Rome’s history, the Aeneid.

Contrast that with a modern statement from the Cato Institute that “groundwater aquifers are not a public good.” This implies that aquifers are private, to be exploited privately with no consideration of the communities which depend upon them.

This is the opposite of what the NM Constitution declares in Section 2 of Article XVI that “the unappropriated water of every natural stream, perennial or torrential, within the state of New Mexico, is hereby declared to belong to the public…” Groundwater aquifers are attached to and recharged from surface water.

Virgil’s wisdom about the public good appears in a quotation on the South Corridor of the Library of Congress, the oldest public institution in the country, founded in l800. The notion of the public good is so deeply engrained in American culture it’s startling when one finds a political movement that vigorously, even militantly, denies the existence of the public good at all. That’s at the heart of libertarianism as presented in the voluminous writings of the Cato Institute, the leading think tank of the Republican party at the moment.

It takes its name from perhaps both Cato the Elder and Cato the Younger, severe Roman magistrates who opposed dictatorships which includes the Younger’s struggles against Julius Caesar, when they threatened elitist privilege in the already corrupt Roman Republic. The Catos were not libertarians. They were ferocious defenders of hierarchy and class distinctions but also of what Cicero called “mixed government,” an early form of the balance of powers that influenced the structure of our own government. Executive power is kept in check by popular assemblies and a ruling class that comprised the Roman Senate where vast power resided.

The Catos were staunch defenders of balanced government, not advocates of virtually no government at all like the Cato Institute.

If Governor Susana Martinez’s environmental record has you worried it’s because she is what might be called a Catoist. She believes in the elimination of most environmental regulations as does the think tank that supports her.

The Cato Institute sees the natural world as having no intrinsic value, only a commercial value in the marketplace. It believes individual preferences always trump considerations of the public good. They are anti-science considering scientific findings mere preferences and opinions. They appear to deny the validity of the methods and findings, and even the fruits, of the scientific revolution. Only private “freedom” in a “free marketplace” matters. It’s dog eat dog, might makes right, and don’t even mention the existence of the “commons,” resources that we all hold in common – like air and water. Economic regulation to Catoists is a violation of private economic freedom.

Here are some self-evident quotations from item 44. Environmental Policy, in the Cato Institute Handbook for Policy Makers:

“Although environmental debates sound like they’re arguments about science and public health (with a smattering of economics tossed in), they’re really debates about preferences and whose preferences should be imposed on society.”

I suppose they mean here that some people prefer to be sickened by polluted air and water and some don’t. But seeing as how air and water are common to us all, how do we let one person who prefers pollution to get polluted from a common resource without polluting the resource for the rest of us?

“Consider the dispute about the regulation of potentially unhealthy pollutants, the central mission of the EPA. The agency examines toxicological and epidemiological data to ascertain the exposure level at which suspect substances impose measurable human health risks. Even assuming that such analyses are capable of providing the requisite information (a matter, incidentally, that is hotly debated within the scientific and public health community), who is to say where one risk tolerance is preferable to another.”

There is no “hot debate” about the ability to ascertain hazardous levels of human induced toxicity. The notion of choosing between this “risk tolerance” and that “risk tolerance” is absurd. Why should I be subjected to the health risks that are acceptable to some but not to me? If I don’t mind smog I can’t go ahead and create smog and breathe it without my risk tolerance inflicting itself upon those who have no tolerance for known health risks associated with smog.

The Cato Handbook goes on to say that “within limits, there are no right or wrong air or water quality standards.” How can they write that with a straight face? They are denying the entire history of public health science. I suppose they would say that cholera-laden water might be a preferred risk to some people who don’t see cholera as a “wrong.” According to Catoists they have a right to cholera inducing water if they want it. But what if I don’t want it? Well, tough. “There are no right or wrong air or water quality standards.”

“Science can inform individual’s preferences but cannot resolve environmental conflicts. Environmental goods and services, to the greatest extent possible, should be treated like other goods and services in the marketplace. People should be free to secure their preferences about the consumption of environmental goods such as clean air and clean water regardless of whether some scientists think such preferences are legitimate or not.”

So not only are we seeing here that Catoists believe public health science has no place in political decision making, and that scientific consensus is worthless, we’re also supposed to believe that the environment has no intrinsic, no aesthetic, no spiritual, no psychological or even physiological value. We are asked to believe that the environment is merely a source of goods and services to be exchanged for money in the marketplace by private interests unencumbered by public health concerns because, fundamentally, the public doesn’t matter, only individuals do, even if individuals form the public and would be vulnerable to all manner of savagery and accident without public institutions looking out for their collective interests as individuals and as members of a polity, not merely as consumers of goods and services. And, of course, if only individuals matter that includes the “corporate person” too whose vast wealth feeds massive propaganda campaigns that are protected speech according to the Roberts Supreme Court.

It doesn’t matter that uranium milling took place many years ago in Moab, Utah, for instance, and that the highly toxic tailings were piled up near the Colorado River within 800 feet of its banks. Who’s to say whose preferences matter, the company which dumped the poison stuff near the river or the preferences of 40 million people who drink that water. And will the company have to clean up after itself? It didn’t do a thing about its waste because it preferred not to spend its profits on public health concerns. So now the taxpayers, the citizens, the public of the United States, in order to protect its health, must spend multiple millions of dollars to clean the mess up for the company who’s now out of business.

The Cato Institute seems to think that evil does not exist in the world. That the marketplace is free of unfairness, cheaters, chiseling, deceiving, avoiding responsibility, and sometimes even killing if it means improving profits. To the Cato Institute the marketplace is holy, and operated by holy people whose own preferences are so pure in motive that the more money they have the better their preferences are for the rest of us, the public, which, by the way, in the Cato world doesn’t exist as a meaningful reality.

Let’s don’t vote for politicians whom Catoists and their hirelings influence. Let’s stop doing this to ourselves as a body politic anymore. Let’s think of ourselves, in a Virgilian sense, as guardians of the public good.

If the noblest motive is the public good, the most ignoble motive is private gain at the expense of public health -- health which is always a good.

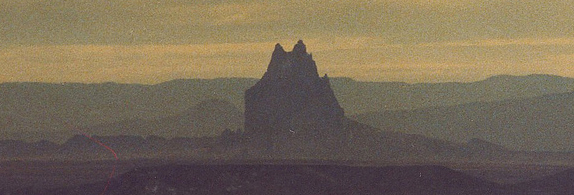

Why We Love New Mexico – Shiprock

The first time you see Shiprock, or even a great photograph of it, you know you’re seeing something holy. If you are a Navajo it is an object of religious and cultural iconography with the name of “winged rock” according to the Navajo-English Dictionary. If you’re a poet, and New Mexico turns most people into poets at one time or another, Shiprock’s soaring presence is one more confirmation of the ever unpredictable and mysterious magnificence of the physical universe and our unique part of it here.

Shiprock, which got its anglo name from the image of a l9th century clipper ship at full sail, rises above the desert floor of the Four Corners region to a height of 7,177 feet, very near the Arizona border. It’s what remains of the throat of a long extinct and vanished volcano whose lava neck hardened into igneous rock around 27 million years ago.

It really doesn’t matter how many times you see Shiprock. You want to see it again and again just to recapture that first sense of awe and the sublime feeling of gratitude for being a part of this world that seeing it brings.

But Shiprock these days is an obscured place, a tarnished visual relic that’s often not there at all to the naked eye. When you spend time on the south-facing balconies of Far View Lodge at Mesa Verde National Park, for instance, and look back into New Mexico, you used to know that you’d be graced with a far flung view of the San Juan Basin and its most prominent land form, the flying rock face of Shiprock. But not today.

From Mesa Verde, Shiprock is frequently almost invisible owing not to what oil and gas people and their government bureaucrats call “haze,” but to downright smog. It’s so bad in the San Juan Basin that it reminds me of Los Angeles in the l950s when older folks were warned to say inside and breathe though damp cloths when the summer smog and stifling heat turned killer.

The “haze” around Shiprock is the worst rural air pollution in the nation.

It’s ironic that in 2008 the American Lung Association gave Albuquerque an A rating as one of the country’s least polluted cities when it comes to ozone, a chief component of “smog. But the source of Albuquerque’s electricity, the power plants in the Four Corner’s region, are among the major creators of “haze,” smog, or what we might just as well call damned unhealthy air.

Aside from the 30,000 or so oil and natural gas wells in the Four Corners pumping away with their smog producing engines 24/7, the two coal-fired power plants in the area are, it’s not a stretch to say, unnatural disasters in their own right. To quote myself in The Orphaned Land, (p.252) “The Four Corners Power Plant in Fruitland, New Mexico, owned by Arizona and New Mexico utility companies, is ‘among the 50 dirtiest power plants in the nation based on its emissions of nitrogen oxide, carbon dioxide, and mercury,” according to the Durango (Colorado) Herald, whose residents breath the second hand emission of that power plant. “A few miles away in Farmington, the San Juan Generating Station, operated by Public Service Company of New Mexico (PNM) was the nation’s No 21 emitter of total nitrogen oxide in 2004 and was “number 34 in the release of carbon dioxide,” according to the Environmental Integrity Project in Washington, D.C. The Durango Herald declared in a front-page headline in June 2008 that the Four Corners Power Plant’s emissions were “among the worst in the U.S.”

And right in the middle of that hideous and life threatening pea soup is Shiprock, aspiring to the heavens somewhere just beyond our gaze. If we can see it at all, it resembles a smear on the lens of your sunglasses, a handsome and intriguing smear though it may be.

But as transformative as Shiprock is and as sad as it is to have it so obscured, the air in the Four Corners is not about view-obscuring haze. It’s about pulmonary disease, cancer, and heart disease. It’s about tens of thousands of people in New Mexico and in southern Colorado from Durango to Cortez and Mesa Verde whose asthma and general physical well-being are compromised, and whose mortality actuaries are down in the dumps.

Shiprock will endure and weather this out, as it has over the millennia. It is the great symbol of what it means to be still standing. And, for those of us who are, no amount of smog can diminish the Olympian object of hope that Shiprock will always be.

(Photos: Otero Mesa by optictopic; Susana Martinez by PBS NewsHour; Shiprock by Phillip Capper.)

Responses to “Provincial Matters, 9-22-2014”