Desalination, Rationing, Neighborhood Snitches

Before the end of this decade there’s a good possibility that Albuquerque, like El Paso and Alamogordo, will be augmenting its water supply with desalinated brine, will probably be drinking treated waste water some of the time like the folks in Wichita Falls, Texas, and will suffer what Californians are experiencing now with severe water rationing and what feels like draconian water conservation laws and policing.

Although each state varies, what’s happened to the dry states around us might well happen to us in ways peculiar to our politics and natural conditions.

Desalination of brackish water is somewhat easier than desalination of ocean water because there are fewer salts in it. But the residue from brine, unlike what’s left over from ocean desalination, contains minerals characteristic of the geology of the region. That’s why desalinating brine in New Mexico, with its large areas of arsenic in the soil and water, has serious associated health issues. It’s estimated, however, that some 75 % of New Mexico’s ground water is brackish. So there’s tremendous money to be made in desalination, just as there is in conservation strategies and products. It’s good to keep the latter in mind.

In the jargon of water processing the salty, and perhaps in New Mexico arsenic laden, residue is called “concentrate.” And how you handle it and render it harmless is the key environmental issue of the water cleaning process.

Desalinated water costs, by most estimates, about four times as much as pure pumped water. The plant has a high initial cost, some $87 million in El Paso, and consumes relatively huge amounts of power. Desalination power sources in the Middle East are run by natural gas plants attached to the desalination machinery. With the U.S. Department of Energy supporting the manufacture of small self-contained modular nuclear power plants, it seems likely they will be used to power desalination operations.

El Paso will surely be the model of desalination processes for New Mexico’s cities. Their desalination plant, named after former Texas Senator Kay Baily Hutchison, is the largest inland desalination operation in North America. Smaller operations exist inland in Texas and along the Gulf of Mexico. The El Paso plant produces about 27.5 million gallons, or 84 acre feet, of fresh water per day. That increases the city’s water supply by around 25%. They desalinate brackish water from deep below an aquifer known as the Hueco Bolson which is also a water source for Juarez, Mexico. The city of El Paso partnered with the U.S. Army at Fort Bliss to research and build the desalination plant. A desalination plant in Alamogordo, New Mexico, draws brackish water from the Tularosa Basin and could produce as much as 2.8 million gallons of fresh water a day. Alamogordo is also the site of the Brackish Groundwater National Desalination Research Facility, a center for technological analysis and development.

The big issue in El Paso, as it would be anywhere inland desalination is practiced, is what to do with the “concentrate.” El Paso has opted for “deep well-injection.” City water authorities thought about evaporation, but that would still leave salt and other concentrates. In deep well injection, “the concentrate is placed in porous, underground rock through wells. The sites would confine the concentrate to prevent migration to fresh water, provide storage volume sufficient for 50 years of operation and meet all the requirements of the Texas Commission on Environmental quality.” Make of that what you will. I’m not exactly sure what the 50 years refers to – that it will take 50 years worth of concentrate, or the porous rock will keep the concentrate from “migrating” into fresh water for 50 years. And I can’t say the Texas Commission on Environmental quality inspires confidence, any more than the Department of Energy does when it comes to WIPP and its underground storage. But that’s for another discussion.

When the going gets tough, the people suck it up and stymie their yuk and gag reactions. Wichita Falls in north central Texas, not far from the Oklahoma border began in July purifying millions of gallons “black water,” in other words water and the stuff you flush, to bring it up to drinkable standards. It’s called, ingloriously, “toilet to tap.” But Wichita Falls is trapped in a devastating drought that may see the complete emptying of the city’s reservoirs, despite the city ban on outside watering and conservation efforts that have saved some 45% of normal usage, according to the Associated Press.

Washing your face in the morning with toilet to tap clean water, as unrefreshing as that sounds, is incalculably better, it would seem, than paying hundreds or even thousands of dollars in fines like improvident water wasters in Santa Cruz, California. And the fines are better, I’m sure, than being snitched on by angry neighbors who see you as a water scoff law and want to make you pay.

As the drought increases in the West, cities will no longer have the sugarplums of “growth and development” to dream of. They’ll have to settle for the hot, dry, nasty reality of having to do barely enough with less and less and less. And if desalination does turn out to cost four times as much as pumped and treated clean water, many of us will find our household budgets caught between high priced water and high priced gasoline. Water, of course, has to come first.

Fracking v. Solar

Fracking is a bridge to nowhere. It’s supposed to produce enough natural gas to hold us over until we have the brains to develop efficient non-polluting, renewable, alternative energy sources, like solar and wind power. But the frackers, making billions upon billions, say that solar and wind power are mythical, useless, expensive, and so inefficient they won’t survive in the marketplace. Frackers constantly attack the future their bridge of gas is supposed to lead to.

They oppose tax breaks for alternative energy. They oppose any and all federal subsidies for alternative energy. They create huge propaganda campaigns to disparage the idea of an alternative energy future. They deny climate change and the role of fossil fuel pollution in creating it. And all the while they themselves take every advantage from the taxpayer they can, thereby ruining the very notion of a competitive market atmosphere.

A bridge to nowhere.

The logical disconnect in the PR messages of the frackers, and the fossil fuel industry as a whole, denies rationality and the public’s increasing desire to shed its gullibility. Natural gas is not a bridge to a brighter future. It’s simply a little slower way to commit global suicide by climate change.

Frackers fume at the idea of regulating their industry to keep production processes from adding greenhouse gases and from messing around with drinking water in the vicinity of their wells. But, of course, it’s not just oil and gas extraction that leads to climate change. It seems stupid to even have to say that. It’s the use of those fossil fuels that causes the problem.

In comparison, wind and solar energy have near zero impact on climate change.

A recent piece on Colorado’s efforts to regulate fracking by Joe Nocera in the New York Times chides Coloradans for their naiveté in thinking they could have an impact on limiting or stopping the extraction process and lambasts those who argue that fracking should banned because it’s a health risk. Nocera tells them to “dream on.” The column does acknowledge that the venting of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, might be fracking’s “Achilles heel,” but it says nothing about fracking’s contribution to creating energy sources that lead to climate change.

Joan Brown, a Franciscan nun who is the executive director of New Mexico Interfaith Power and Light, puts it all in perspective. We interviewed her last week on Insight New Mexico. She said straight out that climate change was the great moral and ethical challenge of the 21st century.

The fossil fuel industry doesn’t agree with her, of course. But whose opinion is more reliable here, people who make uncountable billions of dollars off of fossil fuels or a woman who has devoted her life to the service of nature and the well- being of human kind? Who’s more credible?

Even though frackers deny it, their process leaks and accidents can and have destroyed local water supplies. There is no doubt that fracking causes earthquakes, some of them very big, some of them coming in unnerving clusters.

Not only is it a bridge to nowhere, it is one of the causes of a dystopian future of rising sea levels, displaced populations, disease, and attendant human catastrophes of violent change.

The other side of the abyss that natural gas is supposed to bridge has no water contamination issues, no earthquake issues, no carbon issues, virtually no issues at all of any negative consequence to human populations. So why do we still insist on using the bridge while working to destroy the bridge’s destination. We all know the answer. Big bucks, very big bucks.

Let’s just take solar power in New Mexico. It’s definitely on the other side of the abyss. With the proper incentives it could do virtually everything natural gas could do but without the fatal side effects. Imagine what might happen if all the impediments were lifted from solar power and it was let loose on the market with enough capital, tax incentives and subsidies to keep it competitive with fossil fuels. It could revolutionize the world.

Even with precious few of the perks natural gas and fracking get, solar power is growing in our state. According to The Solar Energies Industries Association (SEIA) the Cimarron Solar Facility generates enough electricity to feed over 6,100 homes. The Macho Springs Solar Project in Deming is under construction. When it’s finished, it will light up 10,200 homes. More than 87 solar companies operate in New Mexico and the state is ripe for more. One application of sun energy is in disinfecting large quantities of water through distillation or heat cleansing. The technology is well known. The World Health Organization recommends using sun power to clean water in developing countries. It’s estimated some two million Third World people use solar cleansing to produce drinking water.

The other side of the natural gas bridge is the possibility of a sustainable non-polluting future. How soon we get there has much to say about the outcome of the greatest moral and ethical challenge of the 21st century.

Why We Love New Mexico: Open Space

We love New Mexico as much as we do because so many of us love the free open land around us, and love it enough to do battle with developers and land speculators to actually preserve some of our most beautiful open spaces from urban sprawl.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the City of Albuquerque creating a unit of government called the Open Space Division in l984. People in Albuquerque who loved the land started lobbying the city in the 1960s and l970s to purchase open space to keep our horizons clean of development.

To quote myself in Albuquerque: A City at the End of the World, (pg 83):

In l971, the city made its first purchases of the West Mesa volcanoes. Two years later, major purchases of open space in the Sandia Foothills were made, and a non-development demarcation line for building in the foothills was established anywhere that the slope reached ten percent. By l975, the City/County Comprehensive Plan was approved, with a third of it devoted to open space.

By l989 or so, Albuquerque owned or sustained a controlling interest in 21,285 acres of open space according to the annual report of the City’s Open Space Advisory Board. That made Albuquerque’s holdings of urban open space the fifth largest in the nation. By 2014 open space in Albuquerque amounted to some 29,000 acres. That puts us close to ranking number one in the country, from what I can tell, in terms of percentage of land devoted to open space. That’s a side of Albuquerque that the city’s detractors ignore.

Albuquerque’s Open Space programs and holdings attract hundreds of volunteers who devote themselves to preserving and restoring what gives so many of their fellow citizens such deep pleasure. The Open Space Division has a handsome building of its own on the Westside off Coors Boulevard with spectacular views of the Bosque and the Sandias.

Open Spaces generally refer to lands acquired by Albuquerque City government, but the city co-manages other holdings owned by the state and other entities. The list of holdings is little short of amazing in a development crazed city like ours:

- Aldo Leopold Forest, a loop trail in the Bosque to honor the great ecological ethicist;

- Boca Negra Canyon on the Westside with a rich assortment of petroglyphs;

- Elena Gallegos Open Space in the Sandia foothills;

- Montessa Park in the South valley;

- Paseo del Bosque multi-use trail which goes from the southern to the northern edges of the metro area through the Rio Grande’s cottonwood bosque;

- Rio Grande Valley State Park with its marvelous hidden nature center, wildlife observation platforms and hiking trails;

- Sandia Foothills Open Space which includes more than 2600 acres of steep hiking trails along the foot of the mountains.

Albuquerque open spaces include urban farming projects, innumerable other trails and vistas, Albuquerque’s five iconic West Mesa Volcanoes, and the Piedras Marcadas Canyon trail along the base of the west mesa basalt escarpment.

It still seems improbable to me that a city so historically devoted to subsidizing urban sprawl would also have a citizen lobby powerful enough to go counter to the growth-at-any-cost mentality of the city’s leadership and actually preserve huge amounts of open land from subdivisions and their roads and strip malls.

It turns out that many Albuquerqueans also see themselves as New Mexicans who love the state so much that they’ll volunteer their time and energy to saving land from people who look at it only as a commodity with which to gain financial wealth, often at the expense of the emotional and aesthetic well-being of the rest of us.

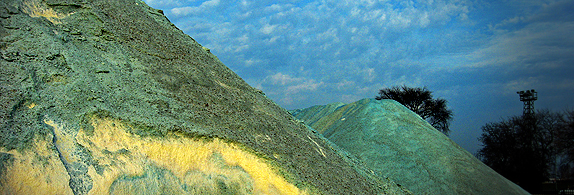

(Photos: Salt piles by John Picken Photography; Aerial fracking view by Simon Fraser University Public Affairs and Media Relations; Elena Gallegos Open Space by City of ABQ Open Space)

Responses to “Provincial Matters, 8-25-2014”