Plutonium Pits in Our Pocket

Many years ago Albuquerque Mayor Harry Kinney, an engineer in the military industrial complex’s facilities at Sandia Laboratories, joked around about how stupid it was for well meaning idiots like me to worry about Plutonium. “Ah, VB, it’s so safe I could carry a ball of it around in my pocket,” he told me with one of his always charming condescending grins.

Mayor Kinney’s attitude is one tiny example of the way the nuclear establishment has tried to downplay the catastrophically and absurdly dangerous potential consequences of its activities.

I was reminded of Harry’s “joke” the other morning when I was reading the Santa Fe New Mexican’s story by Staci Matlock on the Los Alamos National Laboratories (LANL) and its job of making plutonium “pits” for nuclear weapons.

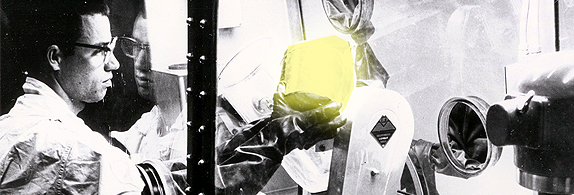

The photograph that accompanied the story showed a man handling plutonium but he wasn’t putting it in his pocket. He was behind a leaded glass window, wearing goggles, and had put his hands and arms in thick rubber gloves into a heavily shielded box so that he was completely protected. In one hand was what the caption called a “puck” of plutonium, “refined from a nuclear weapon pit.” The technician handling the stuff looked quizzical if anything. I just about laughed out loud. Harry might have scoffed at such precautions, but then he came from a time when the precautionary principle hadn’t been recognized as a useful and protective concept.

Precaution is not something the nuclear industrial complex is really famous for anyway. How many times have we heard “there’s no danger to public health” following an announcement of the leakage or appearance of some deadly nuclear substance in the water supply or general environment? It must be hundreds, even in my limited experience. It would be comical if it weren’t for the hellacious consequences.

Even last week when we heard of the “impossible” happening at the Waste Isolation Pilot Project (WIPP) outside of Carlsbad – Plutonium and other poisonous nuclear debris getting into the air around the area, over a half a mile away, leaking from a site that was supposed to be secure for 10,000 years – even then we heard the old refrain. There, there little folks, nothing to worry about here.

Most of us probably have a very foggy idea of what goes on at LANL or why those incredibly thick gloves the technician was using, and virtually everything else that had come in contact with Plutonium, have to be sent to WIPP to be stored in canisters a half a mile underground in a salt mine. And probably even a smaller number of us realize that Plutonium “pits,” the highly radioactive super dangerous explosive cores of America’s nuclear arsenal, are produced there. In fact it’s the only place in the country that does produce them now. The exact number is not available, but there’s a chance that some 80 of them a year could be manufactured there starting not too long from now, producing untold amounts of nuclear waste that would be added to the tons of nuclear waste already housed at LANL, some of it bound for WIPP.

It should go without saying that if even one of those “pits” actually exploded in a bomb somewhere – an unthinkable and unconscionable circumstance – the world as we know it would be changed forever. The use of a nuclear weapon would cause not only millions of deaths, as today’s bombs are astronomically more powerful than the bombs used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki which killed as many as a quarter million people, it would end forever the myth of nuclear arsenals serving as deterrents against nuclear war. Use one nuclear weapon and the possibility of using others in retaliation, or as part of a politically legitimized strategic option, would become the actual horror the world has feared since the end of World War II. And who knows how many such explosions, with their fallout, it would take to jeopardize all life on this planet?

So once again millions of dollars are being contemplated to construct a “pit” manufacturing facility at LANL to create explosive elements for weapons that simply can’t be used and, should sanity prevail, never will be used but which, in the process of manufacturing them, create deadly waste that is proving to be next to impossible to dispose of in a way that is truly safe for the rest of us.

These dilemmas are part of the reason the nuclear industrial complex, which includes LANL, Sandia National Laboratories, and WIPP in New Mexico, has seen the erosion of its public credibility over the last several years. Combined with a 24 million gallon jet fuel spill at Kirtland Air Force Base, the largest by far in the nation, and the military in New Mexico isn’t looking as benign as it used to, particularly when it drags its feet and offers up PR puffery of “no danger here” and self-justified inaction.

It’s beginning to get very old. I’m reminded more and more of the Collingridge Dilemma. It’s described brilliantly by journalist Evgeny Morozov in a book called This Explains Everything edited by John Brockman. Collingridge’s basic insight was that we “can successfully regulate a given technology when it’s still young and unpopular and thus probably still hiding its unanticipated and undesirable consequences – or we can wait and see what those consequences are, but then risk losing control of its regulation.” Collingridge himself wrote “When change is easy, the need for it cannot be foreseen; when the need for change is apparent, change has become expensive, difficult and time-consuming.”

And so the owners of this uncontrollable technology who did nothing at the start to take precautions with it, even when they knew it was dangerous, now have to lie about its dangers because “change has become expensive, difficult and time-consuming.” The man handling the plutonium “puck” in the photograph was looking at it through some form of leaded glass, a process developed early on in the Manhattan Project because, even then, they knew better than to joke about carrying a glob of it around in your pants. I know this because I have a small ash tray of very heavy yellow colored glass made by a late friend who did “war work” long ago devising the glass when the nuclear industrial complex was young and perhaps “controllable,” the chances of which now certainly seem to be buried deep in the realm of impossible things.

Robinson Jeffers in New Mexico

I wonder what the poet Robinson Jeffers would make of WIPP and the continued production of nuclear weapons. Labeled lately as a “noir realist,” Jeffers was perhaps the first great American environmental poet, not a nature poet, or a Romantic poet, but someone who saw human existence in the context of the rest of life and the rest of the cosmos. Jeffers’ view of the world of human folly was dark and unforgiving. In his poems and his public statements he was never less than painfully candid about his feelings of disgust for humans who destroy their landscape, ravage each other, ruin the world for other creatures, and worship themselves and, what we might laughingly call now, “human reason.” Placing humans at the center of everything, Jeffers thought, was the crowning folly of the human species, one that lead to misery after misery.

Jeffers visited Taos numerous times in the l930s staying with Mabel Dodge Luhan. He had what might be called a prophetic sensitivity. He was well aware that the lull in human savagery after WWI was coming to a close with the appearance of Nazi war machinery already reducing tens of thousands to useless gore. Perhaps Jeffers came to New Mexico to experience the energizing powers of our landscape as D.H. Lawrence and Aldous Huxley had done in the l920s. But, as far as I can tell, Jeffers only wrote one poem about his experiences here. It’s called “New Mexican Mountain” and was published as a frontispiece to an anthology of New Mexico poetry since l960 called In Company. Jeffers’ concluding stanza reads in part: “Apparently only myself and the strong/Tribal drums, and the rock-head of Taos mountain, remember that/civilization is a transient sickness.”

A fierce pacifist who opposed war of all kinds, Jeffers has been accused of being a misanthrope and a nihilist. Famous enough in his day for a cover of Time magazine and a postage stamp in l973, Jeffers opposition to WW II resulted in withering criticism and his reputation being submerged for decades.

As a political and environmental poet, he coined a philosophic position which he called “inhumanism.” Jeffers advocated a “shifting of emphasis and significance from man to notman; the rejection of human solipsism and recognition of the trans-human magnificence” of the world. Jeffers lived all his adult life in Carmel, California, overlooking the Pacific near Big Sur in a house he helped build from stone called Tor House. The older he got, the darker and more critical he became. This is not to say that he was a nihilist. He loved the world with virtually all he had, but he was never gulled by “human solipsism” as he put it.

In his poem, “The Inhumanist,” Jeffers has the character of the title say:

“The beauty of things –

Is in the beholder’s brain -- the human mind’s translation

of their transhuman

Intrinsic value. It is their color in our eyes: as we say

Blood is red and blood is the life:

It is the life. Which is like beauty. It is like nobility. It

has no name – and that’s lucky, for names

Foul in the mouthing. The human race is bound to defile,

I’ve often noticed it,

Whatever they can reach or name, they’d shit on the

morning star

If they could reach.”

Jeffers often said what many of us think but can’t bear to believe. But I’m glad he said it. It’s impossible to travel the full spectrum of opinion unless you can find someone writing with passion at the deep dark end of the possible as well as someone working at the shiny, hopeful, trusting beginning of what will be. But a spectrum is more like a Mobius strip than a long, seemingly endless tape worm stretched between the plus and the minus of things. Jeffers’ eyes see the darkness, and we must look through his lens if we want the whole picture, while knowing it is not the only picture.

As an older person, and a grandparent, with responsibilities when it comes to the future, I know that one of the worst mistakes that angry despair can cause in us is to equate the malice, incompetence, brutality, sociopathic cruelty and rank stupidity of those who abuse their power with a representation of the whole of humankind. It is so obvious that we as a species are so much more than our tyrants and torturers, so much more than our solipsists and megalomaniacs, so much more than our carelessness and fraud. I honor Jeffers for seeing into the dark with such fearless candor. But I remember him most for poems like “The Excesses of God”:

Is it not by his high superfluousness we know

Our God? For to be equal a need

Is natural, animal, mineral: but to fling

Rainbows over the rain

And beauty above the moon, and secret rainbows

On the domes of deep sea-shells,

And make the necessary embrace of breeding

Beautiful also as fire,

Not even the weeds to multiply without blossom

Nor the birds without music:

There is the great humaneness at the heart of things,

The extravagant kindness, the fountain

Humanity can understand, and would flow likewise

If power and desire were perch-mates.

The Yuk Factor in Economics

Imagine having a plate of rotten bird carcasses, cat poop and dead spiders set in front of you in a restaurant. You’re response might well be summed up in the work “Yuk,” which expresses “repugnance, disgust, abhorrence,” according to David Edmonds, one of the editors of a book from Oxford University Press called Philosophy Bites. “Yuk” can also be a response to situations or ideas of that are ethically repugnant.

Julian Savulescu, director of the Oxford University’s Uechiro Centre for Practical Ethics said that along with our revulsion toward certain kinds of foods, many “disgust reactions are evolutionarily programmed in order to protect us from toxins or adverse situations.” He explains, “the revulsion to incest has a very good biological reason; you’re much more likely to have a genetically abnormal child with a relative.”

Savulescu warns us in Philosophy Bites to be careful with “yuk” responses and not project primeval reactions on modern situations to which they no longer apply, owing to new knowledge or changes in custom.

The “yuk factor” is, however, a very useful component in a citizen’s BS detector, especially when we’re exploring the smoggy logic of the “dismal science” of economics. Certain modern applications of old ideas can cause revulsion. And it’s important to pay attention to one’s disgust toward such concepts, and for good biological reasons as well – i.e. survival.

Last week in Common Dreams via TruthDig, Chris Hedges reported on an encounter with another Oxfordian, Avner Offer, an emeritus professor of economic history. Offer defines the “ruling economic ideology” of much of the modern Western world. It’s called a “just-world theory,” and dominates the thinking of those “one percenters,” and their close relatives, who have almost all the money there is in the world. Hedges defines it as a theory “that posits that not only do good people get what they deserve but those who suffer deserve to suffer.” Offer says this theory is “a warrant for inflicting pain.”

My “Yuk response” to this is as vehement as it can get. What an utterly repulsive idea. It goes against everything a civilized society should hold as true. It defines reality in the cruelest way possible. Yuk!

Hedges cites Offer further: “A just-world theory posits that the world is just. People get what they deserve. If you believe that the world is fair you explain or rationalize away injustice, usually by blaming the victim.” Offer says that Fascism and Bolshevism and Neoclassical economics were all just-world theory systems.

Hedges quotes Offer quoting Milton Friedman, the economic advisor of Ronald Reagan and a mainstay of Neoclassical economics, “The ethical principle that would directly justify the distribution of income in a free market society is, ‘To each according to what he and the instruments he owns produces.’”

Offer continues: “So, everyone gets what he or she deserves, either for his or her effort or for his or her property. No one asks how he or she got this property. And if they don’t have it, they probably don’t deserve it. The point about just-world theory is not that it dispenses justice, but that it provides a warrant for inflicting pain.”

What it posits is a justification for gross income inequality, slave/master relationships, and a de-spiritualized form of economic predestination: If you’ve got it, you’ve deserved it. If you don’t have it, it’s all your fault. What you have determines your ethical validity. Material possessions signal moral worth. That’s the thinking behind some folks arguing that cutting food stamps is “good for them,” i.e. good for the hungry. It’s the thinking behind people who believe consumers make rational economic decisions when they are being coerced to purchase things they didn’t even know they “needed” or “wanted,” pressured to do so by advertising.

A just-world theory argues that the world is rational, reasonable, and devoid of luck, of accident, of misfortune, of illness, aging, youth, social class, growing up in poverty, or belonging to a marginalized social group. I suppose a just-world economist would have to say that if you got cancer or heart trouble or arthritis or the market collapsed and took all your savings or that you were robbed or the victim of domestic abuse or the victim of bullying or got caught in a tsunami that you probably deserved it. That makes about as much sense as saying that someone who inherited a fortune deserved it. Or someone who was born with a physical handicap deserved it. Or that someone who got rich deserved it. It’s as unacceptable to say that all rich people are exploiters as it is to say that all poor people are lazy good for nothings. Just because someone is rich does not mean they’re virtuous. Getting rich can be just as much a matter of luck and accident and opportunity as being poor can be.

The just-world theory is socio-pathologic. It motivates people to act and think without empathy or compassion, to elevate the mighty and beat down the downtrodden even farther. As far as the “yuk factor” is concerned, it’s off the charts.

It relegates true justice to the dust bin.

(Image credits: Robinson Jeffers photograph by Carl Van Vechten, Hawk Tower by Harvey Barrison, Monopoly balloon by Alistair McMillan)

Responses to “Provincial Matters, 3-10-2014”