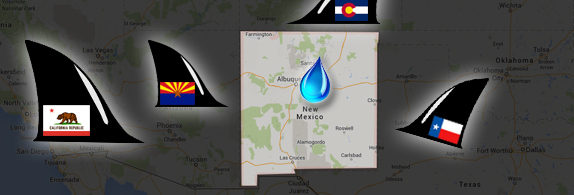

Water Sharks Eyeing New Mexico

Seeing California’s nearly naked mountains in late January sends a shiver of apprehension over the western United States. The Sierra Nevadas are supposed to be snow laden now, building a deep pack that will keep California’s economy and citizens flourishing. But with no snow, California can become a dangerous and opportunistic beast seeking water anywhere it can.

So it’s hard to escape the feeling that a perfect storm of water woes is building up momentum and moving toward us in New Mexico. It feels like we’re on a little raft with giant water sharks circling around us – Texas, California, Arizona, and Colorado – hugely rich states that could prey on the weaknesses of poor states like ours.

I don’t think it’s being paranoid to say that New Mexico is ripe for the taking. We’re suffering from a terrible drought ourselves and we’re already under siege from Texas. If Texas wins its current court case over groundwater use draining the Rio Grande, there’s an awful chance that agriculture in southern New Mexico could be damaged beyond repair, including our cash crops pecans, onions, pistachios and chile. And we could be vulnerable to provisions in the Colorado Compact that would take water away from us because of droughts in California, Arizona, and Colorado, if their allocations are not forthcoming. It must also be said that we have the looming disasters of ground water pollution to contend with in both the Middle Rio Grande Valley and around Santa Fe from the military-industrial complex that we’ve chosen to ignore or minimize since the cold war. And the so-called Copper Rule decision earlier this month by the Water Quality Control Commission, under Governor Martinez’s control, that allows Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold, Inc to pollute water around the Tyrone Mine near Silver City, has conservationists worried that similar rules might allow the Dairy Industry to more readily pollute its groundwater by lifting existing restrictions.

We’re greatly weakened by our lack of a polished statewide water plan with a call-to-arms agenda and the public’s buy-in, by our inability or unwillingness to adjudicate water rights and by the absence of legislative and executive impetus to stash money away for inevitable water wars ahead. Texas, alone, reportedly has a $1 billion water war chest. And I’m sure California, Arizona, and Colorado have substantial armories of water-earmarked funds themselves.

It seems obvious that this is how climate change and its consequences are going to play out in the West – worst case scenarios are coming true. Yes, things change for the best from time to time as well. Respites are welcome but they are not fixes. The November monsoon in Arizona, the blessings of an average and spotty above average snowfall in northern Colorado in the Yampa River basin near Steamboat Springs, the great flood of the Pecos in October and the relief it brought to Carlsbad -- these have brought some emotional relief. But they seem to be, if not quite anomalies, then intermittent wet spells in an increasingly arid predicament. The trend is dry, very dry. And it would take a considerable number of years of consistent wet weather to repair the drought’s damage. And that, at the moment, does not seem likely.

That’s why plutocratic Texas has become predatory, and why California, Arizona, and Colorado might too. New Mexico’s a sitting duck. We have no equitable, share-the-pain, worst case conservation strategy that I know of. We haven’t even thought about it as a body politic. And the few millions that the governor has proposed to spend on water planning and water projects this year is laughably inadequate.

Satellite photographs of California this winter showed the Sierra Nevada snowpack to be almost non-existent and that combined with low snowpack in the Colorado River watershed, is leaving California perilously dry. That’s why California’s governor, Jerry Brown, has declared a drought emergency. Some scientists are worried that this drought could be the worst in many hundreds of years. California has suffered from mega-droughts in the distant past. But this one could be the worst yet. Bryan Walsh of Time magazine quoted Gov. Brown as saying, “it is imperative that we do everything possible to mitigate the effects of the drought.” Walsh added, “the good news is that the sheer amount of water we waste – in farms, in industry, even in our homes – means there’s plenty of room for conservation. The bad news is that if California lives up to its climatological history, there may not be much water left to conserve.”

When it comes to the Colorado River Compact, California has what could be considered senior rights to its river allocation. It’s had nasty wars in the past with Arizona. Nevada a few years ago threatened to basically challenge the whole edifice of the Compact and the Law of the River itself if it didn’t get more water -- which it did. We could see multiple challenges to the Compact in the near future. Who knows what that might mean to New Mexico and its relatively tiny, but important, Colorado River allocation. And there’s the specter of the Imperial Valley, the greatest winter crop producer in the nation, not getting its Colorado River water and spreading food shortages around the west and the rest of the country. It’s possible that the Colorado River’s average flow could be reduced by as much as 35 percent by 2050. The stakes are very high. Too high to be ignored as we’ve been doing.

Some municipalities in New Mexico have been aggressive about conservation, but not nearly enough of them. Water prices and penalties for waste are still way too low. But just as important as planning is raising public consciousness. It’s a legitimate role of government to alert the populace to potential collective dangers. Our governor, along with Albuquerque’s mayor and many members of the city council, is silent about the threats of drought ahead. One doesn’t hear much about water emergencies from many Democratic gubernatorial candidates either and the Legislature is all but mute. Our way of life is changing. We really are going to have less water sooner or later, probably sooner. How much less is anyone’s guess.

What is to be done? For starters, our leaders have to treat this as a real problem, not as some liberal or environmental scheme to be counteracted with denials pretending to be common sense. Jerry Brown is right about California’s plight. And, indirectly, he’s right about ours.

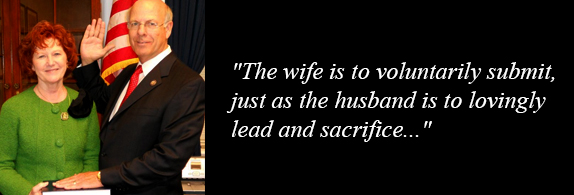

Pierce and the “Submission” of Women to Men

New Mexico Congressman Steve Pierce has become a comedic target for writers and quipsters of progressive blog posts around the nation. He deserves all the darts and barbs he’s getting. No one can really quite believe he wrote what he did about women in his forthcoming memoir Just Fly the Plane, Stupid. In one chapter he reflects on his understanding of scripture and concludes that “the wife is to voluntarily submit” to her husband who’s supposed to “show up” when things get tough and be the man.

Pearce’s religion is his own business and beyond the pale of commentary. But when a lawmaker’s religion drives his public policy, it becomes everyone’s business. It’s not a laughing matter. The misogynist’s core belief is that men are inherently superior to woman and have a divinely inspired right to expect submission and obedience from them. Misogyny is a brutal falsehood on the face of it. It is at the core, as far as I can see, of all irrational hierarchies that assert the supremacy of one group over another on the basis of nothing more than airy myths and stratospheric pronouncements. Misogyny is, in my judgment, the template for racism and classism. It is the root of great evil.

Violence against women is a growing horror in New Mexico, America and around the world. The almost universally accepted statistic is that somewhere around one quarter of American women have suffered sexual assault. Ninety nine percent of their assailants are men. It’s a shattering number and one that could not arise in a country and in a world in which women were seen to be inherently as important and as deserving of civil liberties and equal justice as men. That statistic is the direct result of misogyny, a hatred of women, a situation in which women are expected to submit to their superiors. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s statistics make it clear that sexual assault is not a matter of class. A quarter of American college women report surviving rape or attempted rape before their 14th birthdays. This is the evil of misogyny at work.

Amnesty International this month has begun a major campaign against misogynistic violence, starting its fund raising letter by saying that “more than a decade into the 21st century, women and girls are still being raped, beaten, killed by family members, and trafficked every day.” Amnesty quotes Nobel Laureate Nelson Mandela as saying that “freedom cannot be achieved unless the women have been emancipated from all forms of oppression.”

Gender hierarchy, another term for misogyny, is not the “natural order” of things, as much of Congressman’s Pearce’s political party contends. Pearce himself goes on in his book to explain that “submission” of women in marriage “is not a matter of superior versus inferior; rather it is self-imposed as a matter of obedience to the Lord and of love for her husband.” This is the point at which social conscience is transcended by religion.

Steve Pearce has a 100 percent “pro-life” voting record, voting against funding for Planned Parenthood, federal funding for abortions, and just about anything else that has to do with women’s reproductive health. And his party, the Republican Party, has almost the same record, with a few minor exceptions.

The basic conflict between “pro-life” and “pro-choice” forces deals fundamentally with issues of gender hierarchy and misogyny. Obviously, “ pro-choice” Americans, myself included, do not feel that women are second class citizens of the world, that they are on a lower rung than men in the cosmic scheme of things, that the unborn have superior rights to fully realized human beings. Women are not mere vessels, and that their choice, their volition, their constitutional freedoms are equal under law and equal under humanitarian conscience, with no exceptions, religious or otherwise.

How can a whole political party, and one of its leaders in New Mexico, have a blanket, 100 percent voting record against women’s reproductive rights in a nation in which at least 25 percent of all women of all classes have suffered from sexual assault? Gender hierarchy, misogyny, from whatever source or scripture, is the only answer. It is so deeply imbedded that it becomes an almost unconscious predisposition, unless of course you’re citing the Bible as the moral compass of your views. Then a Congressman is working to establish his religion as the law of the land when it comes to family and gender relations. And that is prohibited by the Constitution.

Keeping the above voting statistics in mind, what woman in America would vote for the Republican Party and its candidates other than those who “voluntarily” submit to males?

Edmund G. Ross

A riveting movie could be made about the life and times of Edmond G. Ross, the territorial governor of New Mexico in the late 1880’s and a man who was on what history has proven to be the right side of the great issues of his day.

Few people have heard of Ross, even those of us with an intense interest in New Mexico’s past. But now his time has come thanks to a detailed, fast moving, insightful biography by Richard A. Ruddy entitled Edmund G. Ross: Soldier, Senator, Abolitionist, published recently by UNM Press.

This is Ruddy’s first book. It’s a prodigious and readable work by a man long fascinated with New Mexico and Albuquerque history. Ruddy retired from a 30 year career in commercial photography in 2002 and three years later launched into a six year research project on Governor Ross, uncovering the story of a man of conscience with a heroic if stubborn streak that served him well on the battle fields of the Civil War and as an anti-slavery mid-westerner who early in his life helped a runaway slave escape to Canada. Ruddy makes Ross, his idiosyncratic personality and the political context of his times, come alive.

Edmund G. Ross is best known for his moment of senatorial glory commemorated in a chapter of John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage. Ross, a Republican from Kansas at the time, cast the deciding vote against the first impeachment trial of a president in American history. President Andrew Johnson was acquitted in the 1868 senatorial trial over Reconstruction policies. Ross was one of seven Republican senators to go against their party. The basic issue was over a punitive attitude toward Reconstruction which viewed the South as a conquered enemy state to be readmitted to the Union piecemeal as the federal government decreed, and Lincoln and Johnson’s more lenient view of allowing the South to repair itself and its culture, state by state in its own way. Some argue that leniency eventually gave rise to the Jim Crow south in which slavery was perpetuated by “other means” when federal authority might have prevented it early on.

Ruddy has a gracefully clear way of getting into the complications of that moment in history. Ross apparently voted as he did, not because he believed in hands off Reconstruction policy but because he felt the pretense of the trial, that Johnson had violated an act of Congress, was specious. And indeed the law, the Tenure of Office Act, was repealed a year later. Ross’s vote was a principled move on the part of an ardent abolitionist and former Union Cavalry officer who fought in the Civil war with passion and conviction. He seems to have thought the trial was politically rigged and a decoy for other issues. He’d have no part of it.

Ross is a stirring example of a man who knew his own mind. While serving as Territorial Governor of New Mexico from 1885 to l889, he was a champion of Native American and Hispanic land grant claims and strongly opposed what he, with a long term perspective, rightly considered land grabs by wealthy and unscrupulous land speculators.

In a report that the territorial governor was required to make annually to President Grover Cleveland, Ross described what Ruddy calls “the fundamental promise of the United States to New Mexican residents” over land grants. Ross wrote “As a rule the lands actually occupied are held by an unimpeachable tenure, having been handed down from generation to generation ….which leads them to suppose that there is not necessity for a public record for their holdings or a formal patent from the government.” Ross railed against land grabbing “rings” and syndicates.

George W. Julian, the surveyor general for New Mexico in l885 wrote publically that the rings and syndicates “hovered over the territory like a pestilence. To a fearful extent they have dominated governors, judges, district attorneys, legislatures, surveyors-general and their deputies….They have confounded political distinctions and subordinated everything to the greed for land.” In trying to clean up the mess Ross proposed a Court of Private Land Claims. In testifying before Congress on New Mexico land grants, Ross said ‘These grants were held under special concessions to individuals or communities….Their ownership was universally recognized, and the indefinite nature and lack of minute description of boundaries was of small moment in a country whose population was so sparse that there was ample room for all and land was practically valueless.” I wonder what Ross and the New Mexico land grant heirs and activists in the l960s would have made of each other.

Ross ended his days without wealth. Needless to say he did not benefit from the land grabbing rings that dominated his tenure in office. He became the editor of the Deming Headlight, found many a good editorial fight, and died in Albuquerque in l907 “a poor man,” Ruddy writes, “but a man who generations later, is still admired for the courage of his convictions.”

What I admire most about Ruddy’s book is the deep level of detail he gives his readers while at the same time guiding them with clear writing and his own sense of fairness and perspective to see the rich paradoxes and hidden realities of the times in which Edmund Ross lived and which he influenced for the better.

Responses to “Provincial Matters, 2-3-2014”