Education for Citizenship

I don’t tend to follow or indulge in conspiracy theories, but when I see public education turned into job training rather than a preparation for citizenship and the mental rigors of self-government, it’s not hard for a conspiracy to come to mind.

What kind of public education would be created by a political party that hates government, thrives off vast income inequality and power differentials, sees workers as bothersome cost centers, and undercuts public services so severely that people starve and bridges, roads, and dams fall apart?

Such a political party would create schools that train people for low paying jobs by equating rote learning and test taking with education. They would create a structure that their major funders – the decision makers of the elite corporate world – would find useful. If government is damaged by sabotaging citizenship, then an anything-goes business “ethic” that is nothing more than feral self-interest can flourish without oversight.

A government hating political party would create an educational curriculum which denies students the mental agility, information, and research skills to perform their jobs as citizen lobbyists watch dogging the attempted corporatization of government, which works to replace a public bureaucracy voter’s can change with a corporate bureaucracy beyond public scrutiny or control.

And so here we are in New Mexico and America. Instead of teaching citizenship, and all that it means in a free society, we’re teaching people to be disposable cogs in a market economy in which government, and its protections against exploitation, is being starved into virtual non-existence, and the notion of freedom itself is replaced by the trickery and insincerity of advertising and the perpetual creation of false demand.

Nearly thirty years ago, the retired dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at UNM, Dudley Wynn, wrote an essay in Century Magazine. A forthright, gloves-off analysis of laissez-faire capitalism, the piece was called “The Lazy Fair.”

He described the “fundamental, basic, historic roots, the great doctrine of economic laissez-faire” as “Let us alone. Get the government and the Church and the old fashioned moralists off our backs and we’ll show you how to create a thriving economy that will serve ‘the greatest good of the greatest number.’…Don’t annoy us with ideas of alleviation of the lot of the poor, the sick, and the suffering. If there were not an abundant pool of hungry, uprooted poor, the system would not thrive, the spinning-jennies in the textile factories would not spin. It may be sad and it all may hurt our feelings a bit, but we have to look at it in larger perspective. Private vices (like greed) make public benefits. Business is business. You can’t contravene natural law.”

Get government off our backs, say these moguls of the Lazy Fair. Get it off our backs and put it on the backs of kids. Distort their natural curiosity, their natural ability to learn anything, even the most complicated languages and social behaviors, bend them to the will of what William Blake called the “Satanic Mills” of laissez-faire economics, and turn them into employees who don’t have the time, the resources or the knowledge to be citizens who demand that we play by the rules, make our profits but truly serve common good.

Dean Wynn asked “What about the consequences of full deregulation of almost everything that has ever been regulated? Think a minute! The answer is, most likely, lowered control over drugs (medicines), increasing monopolization of energy sources, shoddier and shoddier goods at higher and higher prices, increasing rip-offs throughout the entire system, decreasing concern for a clean environment, and many more.”

Get government off our backs. It’s a “simple slogan,” Dean Wynn wrote, but it “has put clear thought, humane common sense, and a lot of devotion to the public good on the run. As Charles Darwin said, ‘Great is the power of steady misrepresentation.’”

In l981, Dean Wynn called American civilization “superficial, unthinking, shallow. We have quit reading. We want pictures. We continue our love affair with the automobile, which has just about done us in. We could not for a moment listen to a leader who would tell us that we have hardships ahead to endure. We’re used to being told that our greatness as a people lies in our going on having forever everything we have ever heard our admen tell us we must want. We are so completely oriented and committed to the consumers’ culture that we assume that anything can be bought, and so we take to the streets to rob and steal (in many cases violently and in too many cases pleasantly, suavely, and legally,) so we can buy the quick fix to relieve all the self-induced unhappiness that has come upon us as the result of our inanity, our passivity, our glutted stupor.”

As we watch education reform, teaching to the test, we see ever more clearly that it is a “lazy fair” too. We’re not just educating robot employees, but robot consumers who do as they are told, want what they are told to want, and spurn the hard work, the free work, of self-government and citizenship, allowing corporate bureaucrats to run the world without elections or debates to bother them.

The New Energy World

As new years roll around, I always enjoy reading the comic book fantasies of the Economist magazine, the voice of EuroAmerican economic conservatism. This year’s edition of “The World in 2014” comes with an introduction by the Economist’s editor Daniel Franklin. Reading it, I wondered if he and I live in the same world at all.

Franklin gives us an economic analysis and some predictions for the year that deal with Brazil, China, the Fed, the “software of human biology,” and “technological inventiveness.” He says “The pace of change in 2014 will arouse both anxiety and excitement.” He even acknowledges, in a single sentence without context, “water scarcity is a growing risk.” But nowhere in the page is a mention made of climate change, the historic ferocity of storms this year, environmental degradation from corporate irresponsibility, and the greenhouses gases released by fossil fuel industries and coal fired power plants. Fukushima is not mentioned at all. And, of course, there’s not even a nod to the desertification of the American West, and the area’s diminishing snowpack, and 30 to 40 million people in the eight major cities in the region who are already trying to make what may prove to be impossible adjustments, should drought continue.

Nor is there any mention about what might save us from a climate change calamity. The Economist is touted as the serious layman’s global economic journal, yet it misses the overwhelmingly most important issue of the 21st Century.

As 2013 leaves the calendar, as the world’s atmosphere continues to heat up, as low snow packs in the Colorado River watershed continue to worsen year after year, it needs to be said, for the record, that many solutions to our predicament are staring us right in the eye. And a lot of us know it. But the powers that be refuse to act.

In New Mexico change is getting too obvious to miss. With receding snowpack, farmers and ranchers in the southern part of the state are seeing, perhaps, the beginnings of a revolution in the very source of usable water itself. Is it possible that climate change will bring not only a continuing decline in snowpack, but also a startling upsurge in monsoonal rain and floods?

If climate change doesn’t so much alter patterns as it does intensify what normally happens within those patterns, perhaps weakening snow packs and more powerful monsoons are simply to be expected. It’s possible that what happened to Carlsbad this late summer when torrential rains ended a killing drought and saved next year’s crops by filling up the Carlsbad irrigation district’s major reservoirs and sending surging waters down the Pecos for the first time in years, is a sign of the future.

What do you do, though, with that flooding water? Farmers in the south are beginning to experiment in their watersheds with what’s called “flood plain reconnection,” which means, generally, that devices and tactics are created to slow the flooding water down and spread it out so the ground and aquifers have more time to absorb it. It also means rethinking levee systems and concrete channels that simply shoot water away into reservoirs without a full chance for its beneficial use.

Perhaps the most obvious changes ahead will come from how we generate electricity. It’s so obvious and has been said so many times that it’s shocking that the change hasn’t been willingly taken up and evolved.

Probably not next year, but soon the world will demand that fossil fuels be heavily taxed and eventually replaced with non-polluting renewable energy. We know this has to happen if we don’t want inland seas swallowing up the shorelines and major coastal cities of the world.

And such a scenario would suit New Mexico just fine. The wind power industry in New Mexico has proclaimed for years that there’s enough moving air in the eastern part of the state to supply all the electricity the state consumes each year. In fact, eastern New Mexico might be to wind energy what the Permian Basin is to oil.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory contends that New Mexico has the potential to generate 1,644,970 Gigawatt Hours (GWh) annually. In 2011 all of New Mexico consumed, from all sources, 22,987 GWh of electricity. Tragically, and unaccountably, only 2,089 of those GWh were generated from wind power.

Solar power has an even greater potential when you consider that it can be almost entirely decentralized, generated from household sized photovoltaic devices. Sandia Labs, I’ve heard, is experimenting with solar panels that are roughly the size of large floor tile, two of which could replace the five large solar panels needed today to power a single home.

While there are no huge solar power plants in the works in New Mexico as of last year, the state has so much potential solar energy that if, say, 47% of the state were covered with solar devices, a preposterous idea of course, it could produce four times the electricity used by everyone in the United States. If one combines decentralized, house-sized solar energy devices, with even a relatively small number of centralized solar power plants and the state’s wind energy potential, New Mexico would be not only energy self-sufficient, but an energy exporter. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, thermal storage of solar energy is 99% efficient in conveying electricity from a power plant over a 24-hour period.

There’s only one reason why New Mexico and the rest of the nation isn’t heading strongly in the direction of replacing fossil fuels with renewable, non polluting sources of energy – and that’s the all powerful, monopolizing competition from the fossil fuel industry. And if you think that’s just renewable industry hype, you need to have your head examined.

Mark Douglas Acuff – 1940 -1994

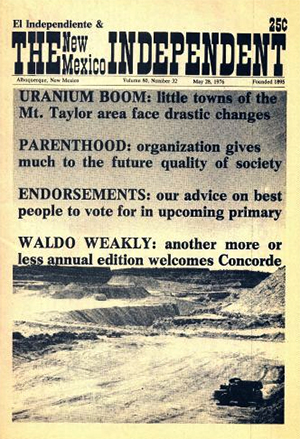

If there is ever a Journalism Hall of Fame in New Mexico, Mark Acuff surely would be one of its inaugural members. Ever a thorn in the side of mainstream journalism – TV, Radio, and the Albuquerque Publishing Company when it housed both the Journal and the Tribune – Mark struggled most of his writing life to create a business model that would allow for a vigorous alternative media in New Mexico and the West. And he succeeded in every way that matters, except perhaps financially. But as far as longevity and quality are concerned, Mark and his wife, Mary Beth, created one of the longest-lived and most passionately admired alternative media outlets in New Mexico during the turbulent l970s.

If there is ever a Journalism Hall of Fame in New Mexico, Mark Acuff surely would be one of its inaugural members. Ever a thorn in the side of mainstream journalism – TV, Radio, and the Albuquerque Publishing Company when it housed both the Journal and the Tribune – Mark struggled most of his writing life to create a business model that would allow for a vigorous alternative media in New Mexico and the West. And he succeeded in every way that matters, except perhaps financially. But as far as longevity and quality are concerned, Mark and his wife, Mary Beth, created one of the longest-lived and most passionately admired alternative media outlets in New Mexico during the turbulent l970s.

The Acuffs’ signature accomplishment was The New Mexico Independent and its subsidiaries in Sandoval and Valencia Counties. He and Mary Beth, the paper’s publisher, bought the Las Vegas, New Mexico, weekly El Independiente in l970. They moved it to Fifth Street in Albuquerque the same year. The paper came with flat bed press that had a line of gas flames which the printed page had to pass across to dry the oil based ink. Pieces of newsprint would frequently catch fire and send the whole Independent staff running to the back shop to stomp out the incipient conflagration.

Mark gave opportunities to many writers, myself and historian Marc Simmons included. Marc reported in his book, Marc Simmons of New Mexico: Maverick Historian, that Acuff casually asked him one day if he’d contribute his column “Dust Trails” to The Independent, and he did. Acuff was like that. In l971, he casually asked me if I’d write reviews for The Independent. I agreed and started writing something called “City Review” which I did every week for the next eight years.

But the New Mexico Independent was predominately the work of Mark’s genius and Mary Beth’s values, tenacity, and worldly wisdom. With the exception of a few other writers, Mark wrote the paper himself. His enormous energy, curiosity, biting humor, and willingness to never pull a punch made him notorious in a way around the halls of political power in our state, and made him one of the most popular and even feared writers New Mexico’s produced. The terrible shame is that The Independent was, like all papers, an ephemeral medium. Mark never published books. And though The Independent is archived at UNM and in the Albuquerque Public Library, those are the only places I know of where one can read his work.

And what great work it was. Though he didn’t like to be categorized politically, he coined the term “Mama Lucy Gang” and applied it to a number of liberal and progressive New Mexico legislators in the l970s who worked for the betterment of the poor, who were active civil libertarians, and who strongly opposed those pre-Reagan era forces who fulminated against the use of government to level economic playing fields, preserve national parks, wilderness and human treasures, conserve resources and protect the environment.

The business side of The Independent had a shining moment in the mid-l970s when all its journalistic potential was brought to full flower by the Acuffs’ association with Didier Raven, an entrepreneur who loved the paper and who offered to sell ads for it. Didier, it turned out, was a master. He sold ad space in The Independent so aggressively that the paper jumped from something like 12 pages to 48. This meant that Mark would have to write more and more copy every week. And so would the rest of us. But the burden fell to him. He produced food columns under the name of Duncan Gonzales, which awarded what became the famous Five Hongo prize for the best food in town. He wrote a Wheels column by Parnelli Gonzales, and Ski column by Jean-Claude Gonzales, and many others I can’t remember. He was prodigiously productive and did most of his own reporting and fact gathering.

One of the happiest brainstorms he had was the creation of the New Mexico Undevelopment Commission, complete with Tee shirts and an annual picnic in Waldo, New Mexico. The picnic featured the legendary cow pie toss and the celebrated mooning of passenger trains that passed slowly through the Waldo Crossing. Many likened the Undevelopment Commission to a comic version of cutting down billboards and other environmental sabotage.

In the early l960s, Mark was the editor of the UNM Daily Lobo and in fact, some say, changed the Lobo over from a weekly to a daily. He was a staunch defender of free speech and an unbending opponent of loyalty oaths and anything smacking of McCarthyism on campus. That got him into a lot of trouble and foreshadowed the many productive troubles his honesty created and that poured from his typewriter over the years.

Mark Acuff died at 54 somewhere near Casa Grande, Arizona, where he was publishing and writing the Pinal Pioneer. He died too young, of course. A memorial for him was held at the New Mexico Press Club in l994, almost a decade after he left New Mexico. Many of us wondered what alternative media would be like in New Mexico had The Independent managed to stave off the wolves at its doors.

(Photos: Republican student by Truthout.org, The Independent from The Santa Fe Review)

Responses to “Provincial Matters, 12-9-2013”