Geodes

Geodes are roundish, rough-surfaced stones that when cracked open reveal dazzling crystals inside. Many of them are volcanic rock that had gas bubbles in them or sedimentary rocks that formed around organic matter, leaving empty spaces to be filled by minerals that seep into them and form crystals over millions of years.

For me, geodes have come to stand for the innocent amazement we feel when we are awakened by the physical beauty of the universe and the moral beauty of loving human kindness. Both are sublime.

These stony miracles of wonder have become Christmas talismans in my family. They act as an antidote to the brutal shopping and calculated consumer baiting that has ruined the Christmas-solstice season for many people I know.

But not for old friend Richard Fox who sends an essay by E.B., White with his Christmas card every year. Written in 1935, it’s called “The Distant Music of the Hounds.”

“To perceive Christmas through its wrapping becomes more difficult with every year,” White wrote. “There was a little device we noticed in one of the sporting goods stores – a trumpet that hunters hold to their ears so that they can hear the distant music of the hounds. Something of the sort is needed now to hear the incredibly distant sound of Christmas in these times, through the dark, material woods that surround it.”

“The miracle of Christmas,” he continued, “is that like the distant and very musical voice of the hound, it penetrates finally and becomes heard in the heart -- over so many years, through so many cheap curtain-raisers. It is not destroyed even by all the arts and crafts of the destroyers, having an essential simplicity that is everlasting and triumphant, at the end of confusion.”

Like that distant music, geodes and the inner marvels of nature, and human nature, can open up in a person a sense that nothing, even in this sad world, need be taken at face value, nor, of course, ever taken for granted. That sense is what William Blake called “innocence regained.” And it is at the very heart of the hidden meaning of Christmas that we can sometimes glimpse moments of glorious happiness and thankful joy.

Perhaps you’ve never had the delight of taking a hammer to a crusty, gray ball of rock and having it fall open to reveal a firmament of sparkling gems like a moonless sky full of shooting stars.

The first geode in my life came to me on a terribly bleak Christmas when I was alone and broke and without my children. A friend came by Christmas Eve and brought me something in a wrinkled brown paper bag, “just for fun, ‘cause I think you need it.” The bag was heavy and I opened it slowly, in need of a miracle perhaps. I lifted the cold, lumpy stone out of its bag, and then … “what to my wondering eyes did appear” … but the starry sky inside a rock. It was so magnificently beautiful and so strangely perfect that it transformed the only truly bitter Christmas of my life into something that opened a universe of possibilities. I will never forget that first shock of being awestruck by the radiant glory of life and feeling gratitude melt the freezing grip of despair.

Many Christmases later we gave our oldest son, who was about 8 at the time, an unopened geode and a hammer wrapped quite nicely in a sturdy box. He wrinkled his nose when he first saw them. But we suggested he hit the geode with vigor, watching out, of course, for his fingers. He smacked it several times to no avail and shrugged his shoulders about to walk away. We asked him to hit it one more time really hard. He did. And the look on his face will remain with me always. It changed from a kind of grumpy “oh the folks are being silly again,” to a wide eyed, jaw dropping amazement. Inside the rugged stone was, indeed, a miniature Carlsbad Caverns, complete with large crystals and bathed with radiant light as if from within.

Like the distant music of the hounds, the beauty of the world can do that to children and to certain adults who still keep looking and listening for that miraculous feeling of being taken out of yourself for a moment by the overwhelming mysteries of beauty, love, and goodness in the human heart.

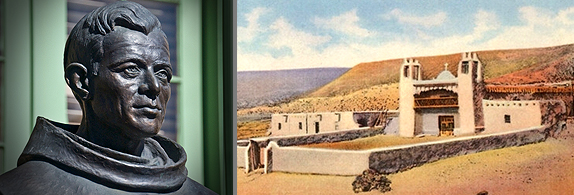

Fray Angelico Chavez and Midnight Mass

Midnight mass on Christmas Eve in the Church at San Felipe Pueblo in l962 opened my eyes to the welcoming and mystical geode of New Mexico’s inner life. It had been a hard year. We’d survived the Cuban missile crisis. The cold war and McCarthy witch hunts were still plaguing our country. But when Fray Angelico Chavez, New Mexico’s first native born Franciscan Priest, completed the ceremony of the mass that night, something happened that brought home to me the reality of worlds within worlds, and how the secret life of our world here is a constant source of reviving strength and hope.

We had followed Fray Angelico on his parish rounds that night, our first child a tiny babe in arms. We went from Cerrillos to Cochiti, to Santo Domingo (Kewa) and finally to the cavernous, gently lit interior of the San Felipe Church, first built in 1705 and rebuilt in the early l800s.

In l962, Fray Angelico had not yet written any of his more famous histories of our state, including his biography of Padre Martinez of Taos, nor his much loved My Penitente Land: Reflections on Spanish New Mexico. He had, however, published a profound collection of poems entitled The Single Rose: Poems of Divine Love. Fray Angelico must have been around 52 that night. He was born in 1910 in Wagon Mound, New Mexico.

I remember a vision of him huddled with three men from San Felipe under a large black blanket, discussing, perhaps, the night’s proceedings. Fray Angelico was at home with his parishioners and they with him. My young family and I had lucked out that night and had found two spaces on pews midway from the altar. The Church was packed. A reverent hush prevailed. Fray Angelico ended the service and stepped into the sacristy and, as he did, the front doors of the Church exploded open with what seemed like a stampede of buffalo dancers filling the aisle. The interior reverberated with the chants and heart drums of the Pueblo world. Our baby beamed with delight. I was so amazed and swept away that my feeble attempts as a young anthropology student to remember what I saw completely vanished in the sublime tumult of the moment.

I remember Christmas Eve l962 as being a moonless, clear night, black as interstellar spaces, freezing cold, and filled with so many stars you could never lose your way in the dark.

Some years later, remembering the ecstatic surrender of that midnight in San Felipe, I wrote to Fray Angelico on the off chance he could tell me something about Santa Teresa of Avila, whose spiritual ecstasy was embodied in a sculpture by Bernini in Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. I really didn’t expect an answer. Fray Angelico was a man of many responsibilities, and I was a struggling poet.

I was astonished by the depth of his generosity when he answered me with a long letter and many references to the saint’s life. He also enclosed a copy of The Single Rose, a collection of devotional poems I have read many times and still, perhaps because of some aridity in me, do not thoroughly comprehend, though one line stands out as a beacon in this season:

“The only love I know lives everywhere.”

Discovering the Perfect Tree

Snow thigh-deep, or on treacherous roads covered with muddy ice, or in howling gales so strong and cold they froze and blew the beans off your fork before they got in your mouth, we’ve seen it all cutting our Christmas trees over the last 40 years or so. We’ve been to Mt Taylor, the Jemez, the Crosby Mountains, the Sawtooths, the Manzanos, and along the steep valley sides of Zuni Canyon. The trees we find, and thank before we cut, fill our lives with such comfort and joy that they take on the feeling of being members of the family. It’s not that it’s the same tree every year, of course, but it evokes all the trees in our lives, and all the friends and family who have trimmed them.

Ornaments from my wife’s childhood, from my mother’s trees, ornaments made by hand, child delights and old folks memories, and lights and lights all over. If you contemplate a Christmas tree long enough you can reach a state of semi-timelessness in which ritual transcends the moment, fuses history into feeling and condenses all the Christmases of your life into single sensation that is a form of bliss if, of course, you’ve come to associate winter and the solstice with the joy of new life, new hope, and renewal of meaning and purpose.

It’s always been important to us as a family to put ourselves out for that feeling, which means traveling long distances and sometimes on treacherous roads to find the exactly perfect tree for the year. All trees are perfect, course, in the natural shaping of their imperfections. But it’s the ritual that gives the trees their form in our eyes. Anything one does repeatedly over the years and decades takes on a mythological power. That’s why, perhaps, ritual is so important to so many people. It becomes filled with meaning that accumulates from the deepest and most significant moments of reflection, your own and those you love.

But as the universe would have it, even in these moments of sublimity, the universe provides comic relief.

There’s nothing like the sound of a fully decorated Christmas tree crashing to the living room floor in the middle of the night. It’s roughly like the wind shattering a thousand tiny windows all at once. Talk about being awakened from a long winter’s nap!

We leapt from our bed to see what was the matter, and what to our wondering eyes did a appear but Lawrence, our first cat sniffing the wreckage and looking a tiny bit put out as only cats can. He apparently had leaped up right into the middle of the tree and brought it down on top of himself. Ever since, we have anchored our trees with strings attached to hooks in the walls. They’re not exactly an homage to Lawrence, but they do keep him in our memory, and have served, we surmise, to keep other cats from doing midnight damage.

In the old days our family all drove Honda Civics, those unstoppable little hatchbacks that could get you anywhere and back. Driving out to the Sawtooth Mountains, past the Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescopes almost all the way to Quemado, we were usually a little caravan of yellow and white Civics intently off on our Christmas adventure. Terrible roads, incredible snows, winds and bitter cold deterred us not. But the spirit of comic relief was never far away.

When those little Civics had big trees on top of them they looked to some of us like a tiny forest on the move and to others like little old ladies in green wigs. And when the Civics all pulled up at the Eagle Guest Ranch Café in Datil they seemed, dare I say, like Santa’s Hondas. Those suppers in Datil were among the best of our lives. Our huge family usually sat at a big table by a roaring fire, warming up and launching in chicken fried steaks and burgers like the lumber jacks we never quite became. And then out again into the cold and night and snow, back down past the VLA to be spotted perhaps by an astronomer on another planet as comic caravan full of happy people.

Often we wonder how we managed to do that under those conditions for all those years. And we have to remind ourselves, laughingly, that we are still doing it even though the kids from that time are now in their 50s and the adults, who never quite saw themselves that way, are in their 70s. That’s the power of ritual and the meaning it embodies. As long as you keep doing it, and honor its values and its heritage, it fills you with energy you didn’t know you had.

(Photos: Geode by Ben Yanis, statue of Fray Angelico Chavez by Ron Cogswell, trees by chintermeyer)

Responses to “Provincial Matters, 12-23-2013”