Humanistic Education Reform

With all the gas and bombast about the “crisis” of American education and educational “reform” in New Mexico, we have much to gain from studying the past about the role of learning in a happy, useful, and fulfilling life.

On the eve of the Nazi occupation of Paris in l940 during World War II, French Nobel Laureate Jacques Monod, one of the great scientists and pioneers of gene theory in the twentieth century, wrote as a young man and resistance fighter to his parents about the education of his children:

I would like to raise them as I was. I would like for them to learn naturally, effortlessly, almost without knowing it, that the love of beautiful things, critical thinking, and intellectual honesty are the three essential virtues. This way, they will like things for themselves, will judge for themselves. This way, they will be real human beings, as there used to be, they won’t be fooled by intellectual snobs and political scoundrels. They will know how to live above and outside of a century which is only getting deeper into infamy, lies and stupidity. [Brave Genius, by Sean B. Carroll, pg 38].

In our own times, with the absurdities of rote education “to the test,” profit motivated “no child left behind” regimentation, and Common Core State Standards that impose national norms on schools to create a standard American person, Dr. Monod’s wishes for his children have a particular poignancy.

His views were echoed thirty years ago in the pages of New Mexico’s Century Magazine when the struggle for education reform was put into sharp perspective by one of New Mexico’s legendary educators, UNM’s Katherine Simons. The “corporatization” and “digitization” of education weren’t the dragons they’ve become today. The struggle then was about education as a civilizing force versus education as occupational training, about educating citizens or job applicants, about learning as a way of life or learning as a way to make a living.

Simons wrote in Century in October l983 about the value of studying the humanities, which do not lend themselves to educational engineering and mechanical instruction:

The humanities, and all that they have to give to the life of the individual, are for sustenance, not for sale. From history, from literature, from philosophy, from science viewed as a human activity, comes the record of man’s living. Little by little, in the course of an education, by infusion from countless contacts with it, the vision of the heritage and its values becomes a sustaining force in an individual fortunate enough to find, in parents and teachers, its active transmission. All too often, however, the recognition of this vision as basic is blurred to the intrusions of more ‘practical’ demands: for training in ‘social adjustment,’ for development of skills directed toward ‘making a living.’ Because the humanities are generally not job oriented, save for the fortunate few who teach in their areas, they have been denied, in this materialistic society of ours, their true place as basics, relegated to the ranks of ‘frills,’ ‘outside activities,’ or worse still, of monuments of the dead past. What does one do with them?

In answering her own question, Simons wrote:

…one doesn’t ‘do.’ One lives with them, drawing strength and insight, pleasure and true happiness from all their accumulated experience of the human spirit, from Job to Chekhov, From Archimedes to Einstein, from the poets and philosophers who knew both the depths and the heights of humanity’s long trek from barbarism. They expand the individual’s ‘margin of awareness,’ to use Karl Jaspers’ phrase, beyond the limits of his own single life and experience, bring wisdom and compassion from the wise and compassionate, courage from the brave, conscience from the just. The individual, contended Plato, is basic to the good society. The humanities, we contend, are basic to the individual.

Of course, the philosophy of learning then was never a dogmatic either/or situation between “work” and “life” any more than it is now, despite the carpet bagger operatives and their ideas for assembly line schools and widget-making tests that plague New Mexico these days. Of course, education must help a person earn a living. And, of course, education must give students a wide and deep enough exposure to the wisdom of the past, and the lessons of history, to help them navigate as full human beings through the ordeals and opportunities of life.

From this perspective, corporate education “to the test” that works to produce predictable workers, rather than flexible and inquisitive innovators, does little to prepare a person for coping with the employment climate of a world in transition, where job security and careers are long gone notions and “corporate loyalty” is a farce. To properly prepare a student for a lifetime of catch-as-catch-can employment, and a society and planet undergoing constant and often unpredictable change, some of it verging on the cataclysmic, education must be directed toward empowering students with passion, enthusiasm, and the skills for a life of constant learning, and not just superficial grazing, but deep diving into the complexities of the world.

If a person wants to make a life and a living in this kind of world, they will shun workshop, assembly line, digitized job training and strike out on their own into the riches of the Information Society. The most important lessons students can learn today are first how to gather deep information, then how to process it, then how to make metaphors and other useful thinking tools out of it and, lastly, to come to understand that half the joy of life is learning how to live, and then, in the other half, living it.

To prepare students properly, build school systems with teachers who are passionate learners, who have been supported in their own learning adventures, who are well compensated, and socially respected. Give them a collegial situation in which administrators and educational bureaucrats morally support and substantially fund a society of learning in their schools, a society that supports teachers becoming ever more richly informed “teaching scholars” steeped in their disciplines, to quote Katherine Simons, and that supports a classroom setting that fosters learning as a joy of life, rather than as a set of onerous dues to be paid to get a low paying job in the future.

“I confess to a conviction that for all the varieties of excellence,” Simons wrote, “a humanistic infusion is a great stimulus to Montaigne’s ‘living appropriately,’ to facing a confused world with quiet and serenity. Excellence in teaching should deserve equal evaluation with other excellences together with conditions permitting high standards in student relationships: providing for individual attention, adequate conferences, careful personal evaluation of students’ writing and general performance, thorough preparation and continued search into subject content.”

With typical modesty, Miss Simons used to say to her praising friends, “good students make good teachers.” And every teacher worth her salt knows this to be true. Good students arise from a culture that values learning, from a society of parents and local and national leaders who know that to learn is the most natural thing a human being can do. If children don’t like to learn, it’s not their fault, but the fault of the learning institutions in which they are, in many ways, imprisoned. Good students are the products of parents and adults who had empowering teachers. But in the last 50 years or so, education has become a marginal endeavor in our society, one in which teachers are disrespected and undercompensated, and put in an inferior position to educational bureaucrats and, now, to corporate bean counters and assembly line managers who know nothing of learning and have no expertise except in profit-making. By doing that, learning, studying, and growing as a free, thinking person all have been relegated to last place. And no amount of testing and brain stuffing will change that.

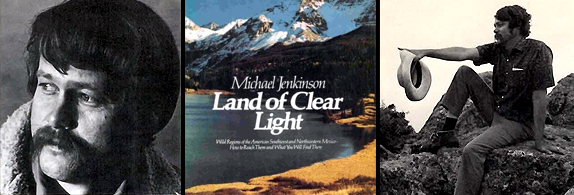

James Michael Jenkinson – 1936 - 1982

The writer and explorer Mike Jenkinson, or Jenk as old friends called him, died of heart disease in Santa Fe in his 46th year, cut short in a way that was tragic to his community of fellow writers and adventurers, but probably not to him. I say that, guardedly but with some confidence, because Jenk knew how to live. One of the great gifts of his was to find nothing that happened to him as cause for disillusionment. Yes, he could be disappointed in himself, but his overwhelming demeanor was one of unabashed gladness and pleasure in it all.

His books, which securely belong in the legacy of New Mexicana, are largely unknown today. They include Ghost Towns of New Mexico: Playthings of the Wind (UNM Press, l967), Tijerina (Paisano Press, Albuquerque, l968), Wild Rivers of North America (E.P. Dutton & Company, 1973), and Land of Clear Light (E.P.Dutton & Company, l977).

Jenk’s writing life might be thought of as that of a wild-card entrepreneur, a tightrope-walking wilderness scout, a crazy-like-a-fox inventor, a man who loved language so much he spent much of his time finding a wild world in which his words and loving humor could flourish freely.

Always on the financial margins, never at a loss for a new adventure, Jenk was like many writers I’ve know, at one time or another. But he seemed to thrive on the precarious and the insecure and never really left the precipice. He once invented a gambling game called Glitter Gulch. He paid for a mockup, and my family played the game quite a lot. A bonanza was just around the corner, but in the end he could only interest his friends. Jenk was ever optimistic that something lucrative would turn up. It infrequently did. But he kept on writing and dreaming, even with a full-time job as an arts administrator for state government near the end of his life.

Jenk was a river runner. And that seems a fitting metaphor for his life as a naturalist and philosopher of the land. He, his pregnant wife, and a friend ran the Yukon River in Alaska in the mid-l960s. Wild Rivers of North America chronicles many of his adventures on fast water with photographer Karl Kernberger. He worked for months in the l970s to set up a film crew to shoot the running of the rapids in the Rio Fuerte in the Barranca del Cobre in southwestern Chihuahua, Mexico. When his team arrived, they found the river in the Barranca too shallow from a long drought to have any rapids. He told that story on himself with a nod and a wink as part of his puzzling history of best laid plans gone awry.

Jenk was born in England but you’d never know it. He came here early in his life and graduated from UNM in l960s with a degree in anthropology. That’s when I met him. He worked as a magazine writer, a book salesman, a ranch-hand, a teacher, a camping equipment manufacturer, a professional actor and a game warden. Afflicted with arthritis from early on in life, and struggling with epilepsy and heart problems, he never appeared to be anything other than in the peak of health. Jenk and I gave countless poetry readings together across New Mexico in the l960s, in bars and schools, at anti-war protests, and in little bookstores. He was a prolific poet, but never published a book of poems. He once had a run-in with Gary Snyder at a big reading over the seriousness of poetry. Jenk was always happy to mix it up, but never with meanness or malice. And he freely admitted he was not a Buddhist and did not see life as suffering to be avoided or transcended. Rudeness never got in his way, either.

He was a satirist, a humorist, a wildman with twinkle, a wizard and a magician by his own lights. When he wrote about land grant fighter Reies Lopez Tijerina in his l967 book, he called him “The Great Communicator.” His assessment of Tijerina’s oratorical genius was as true to form as when the term was used to describe Ronald Reagan more than 20 years later. Both knew how to bring a crowd to its feet. When Reagan became president Jenk used to wonder, over a number of beers and cigars, what it would be like to see the two great communicators blasting each other in a debate.

When writing Land of Clear Light, he pictured early Spanish explorers from the “green and looted lands of the Aztecs” moving north into the “high grassy steppe” of New Mexico and southern Colorado, crossing unpredictable watercourses that could become “torrents raging bank to bank within a matter of seconds, subsiding within hours. The few big rivers they encountered were little more than a braiding of shallow channels through mud banks much of the year” until the spring when they became great floods that “raked at inundated banks with uprooted trees.”

“They came to expect the unexpected,” he wrote, echoing Hericlitus. “A forested plateau might suddenly drop away into the depths of an abysmal chasm. Expecting gold, they discovered pearl beds. Seeking pagan souls to convert” they trudged across vast empty regions. “Despite its contrasts, the Spanish discovered a unifying factor in this region – a certain clarity of sky and air, a sense of space and immensities. Some of them called it the Land of Clear Light.” It’s hard to say it better than that.

When a writer dies too young, there are always wonderings and surmising about the work that never had a chance to be. Jenk, himself, I think would have said his time on the planet was too short, but just right nonetheless.

The National Stuttering Association

The motto of the National Stuttering Association (NSA) is “If you stutter, you are not alone.” Some three million people in America, and some 65 million the world over, suffer from this curious malady, the only disorder it seems, which other people feel free to mock and turn into fodder for jokes and mimicking. Stutterers get used to that, but fear of being humiliated this way becomes one of those strange internal pressures that can contort a small stutter into a total impediment.

I know a lot about this, being a stutterer all my life, albeit one who has learned to mask it and even overcome it from time to time when I’ve prepared for a public speaking engagement in the way I know that works. Once I attended the annual local dinner of the NSA in Albuquerque. I’d been asked to give a speech about how to talk in public, something the organizers hoped would be inspiring. I was particularly fluent that evening and I worried that people in the audience would think I was a ringer. But stutterers can always tell who’s masking and who’s not.

That evening I met dozens of people who had been struggling to build a life, create a social circle, relieve their isolation, and find meaningful and lucrative work while trying to manage the devastating disadvantage of not being able to speak in a fluid and intelligible way. But self-pity was not one of their burdens, though surely frustration and bafflement were.

The causes and cures of stuttering are locked in theories that often swarm and pester sufferers more than they relieve them. But as wise physicians say about most diseases, once you’ve seen one stutterer, you’ve seen one stutterer. There’s seems to be nothing universal about the malady or about its cures.

For some people, self-healing comes with the opportunity to speak in public, and speak a lot. For others who don’t have those opportunities healing can come in the form of ingenious adaptations. Some people find a kind of singing rhythm helps. Others who cannot utter a word extemporaneously have no trouble reading a speech out loud from written texts. Some stutterers can’t read prose to an audience, but have no problem with poetry. Some people I’ve known struggle much of their lives trying to find that secret key that gives them a voice in the world.

I’ve been blessed over the years by my association with children who stutter. Their courage and tenacity is infectious. And they reminded me, always, that we are not alone in this world. For them, the onset of stuttering is like waking up one day and finding that there’s a part of you that other people find either hilarious, irritating, or something akin to a personal failing. Often children will be caught completely off guard the first time they open their mouths to speak and nothing understandable comes out. It’s a terrifying experience. And although stuttering is apparently not associated with early traumas, that first experience can be traumatic and can even, I’ve always thought, create a situation in which a tangled form of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder can develop. As in any PTSD situation, when a child with a stutter finds him or herself in a situation that is associated with stuttering, or even anticipates being in such a place, enormous anxiety wells up. And as all of us know, fear makes anything worse.

That afternoon speaking to the NSA I realized I was very lucky. My work and situation allowed me to practice my way out of speaking trouble, despite the many humiliating abysses. The men and women I met at the NSA were there, in community with each other, to try to figure out what to do and to help others do the same. In that setting, the stigma associated with a “speech impediment” or a “speech defect” had vanished. A gently hopeful, even at times, humorful normality prevailed. It was the perfect atmosphere in which to engage difficult problems in a spirit of optimism and ease.

If you know a child who is beginning to stutter and is struggling with the isolation it causes, go online and contact the NSA for advice and help. “If you stutter, you are not alone.” That realization begins a process of healing and adaptation that, while wholly unique to each evolving child, is familiar and understood by many.

Stuttering is properly called an affliction that comes out of the blue, but it is not a defect or a deformity, and it’s nothing to feel guilt or shame about. And it’s certainly nothing to go into hiding to escape. I liken it to an injury that makes its demands, but that eventually also can be worked around, given the right advice and circumstance, and a lot of patience. The NSA’s camaraderie relieves the feeling that stuttering sometimes gives of being locked in an invisible solitary confinement. What a gift it is to be freed from that.

Responses to “Provincial Matters, 12-1-2013”